By Jonathan Cristol

On July 30, the Taliban confirmed the death of their founder and leader, Mullah Mohammed Omar. Shortly after, the group named Mullah Akhtar Mohammad Mansour, Mullah Omar’s deputy, as its new leader. As seamless as the transition may sound on paper, a split has already formed between Mansour’s supporters and those who favored a successor from Mullah Omar’s family.

Mullah Mansour has spoken out against negotiating with the U.S., an action one would expect any new Taliban leader to take while he consolidates power. It is important to remember, however, that there are two potential outcomes in the current situation within the Taliban: either Mullah Mansour remains in power, consolidates power, and then supports negotiations; or he loses power to someone else, who, ultimately, will support negotiations. The Taliban has a long history of negotiating with the U.S., and while Mullah Omar’s death will postpone negotiations that are ultimately inevitable, it will also make a positive outcome from those negotiations more likely.

Throughout his life and tenure as head of the Taliban, Mullah Omar was always supportive of discussions with the United States because he was not concerned with the world outside of Afghanistan. He was a humble man from a small rural village in Southern Afghanistan. He never spent much time outside of the area and only visited Kabul twice. His primary concerns were domestic policy and the elimination of the corruption and banditry that plagued Afghanistan in the early 1990s. To the extent that he even thought about foreign policy, his primary concerns were Russia, whom he had fought against in the 1980s, and Iran, whose government he believed tried to assassinate him in 1998 by car bomb in Kandahar. Because the U.S. was no friend of Iran, and had an anti-Soviet history, the Taliban saw the U.S. as a natural ally.

From the group’s founding in 1994, the U.S. was willing to work with the Taliban as it was primarily concerned with regional stability, opium production, and oil pipelines. That is, at least until August 7, 1998, when al-Qaida embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania turned American attention to Osama bin Laden.

On the issue of bin Laden, Mullah Omar both approved discussions and ultimately acted as the major roadblock to a solution. Bin Laden was not particularly close to the Taliban leadership, and the Arab al-Qaida “foreign fighters” were not close to the Taliban rank and file. Moreover, the two entities had conflicting political goals: al-Qaida wanted to wage war against the West, while the Taliban were willing to work with the West to achieve local goals.

The Taliban were willing to discuss bin Laden, and Taliban deputy head Mullah Mohammed Rabbani led an anti-bin Laden camp within the Taliban. Even Taliban negotiator Abdul Hakim Mujahid claimed that 80 percent of the Taliban leadership, including the Taliban’s intelligence chief, opposed bin Laden’s presence. Declassified U.S. diplomatic cables show that there were high-level Taliban officials willing to sell bin Laden to the United States. Although much of the content of these cables are redacted, it appears as though the United States would almost certainly have recognized the Taliban government, and offered millions of dollars in payoffs and humanitarian aid in exchange for bin Laden.

There was some hope for a deal on the bin Laden issue, but Omar would ultimately not back down in support of bin Laden. Mullah Omar felt bound by Pashtunwali, the strict code of honor that obligated him to protect bin Laden as his guest, and the two men were bound by blood after bin Laden’s daughter married Mullah Omar’s son. As Steve Coll reported, by 1999, “Mullah Omar had reportedly executed Taliban dissenters over this issue.” Bin Laden might not have had much support from the Taliban, but nobody particularly wanted to lose their lives over him.

Omar’s position throughout the negotiations with the U.S. was that Osama bin Laden’s guilt in the embassy bombings was uncertain, and that he would be willing to have bin Laden tried before an Islamic court in Afghanistan or in Saudi Arabia. This offer was made repeatedly, and was always rejected by Washington.

The pre-9/11 American experience negotiating with the Taliban shows that the Taliban were little concerned with the West and had limited goals. It also showed that most of the Taliban leadership was reasonable and willing, but unable to make a deal. Equally, Mullah Omar was inclined to talk, but was unwilling to compromise.

His death will no doubt increase instability and uncertainty — but eventually it will make a negotiated settlement of the Taliban problem much more likely. The U.S. and Afghanistan should not interfere in internal Taliban affairs, but should offer to negotiate with whomever emerges in charge — even if that person has blood on his hands. Talking is always better than silence, and talking does not preclude force. Yet perhaps most importantly, negotiating is not a sign of weakness, it is a sign of common sense.

*****

*****

Jonathan Cristol is a fellow at the World Policy Institute and a senior fellow at Bard College’s Center for Civic Engagement. He is currently writing a book on U.S.-Taliban relations between 1996-2001. You can follow him on Twitter at @jonathancristol.

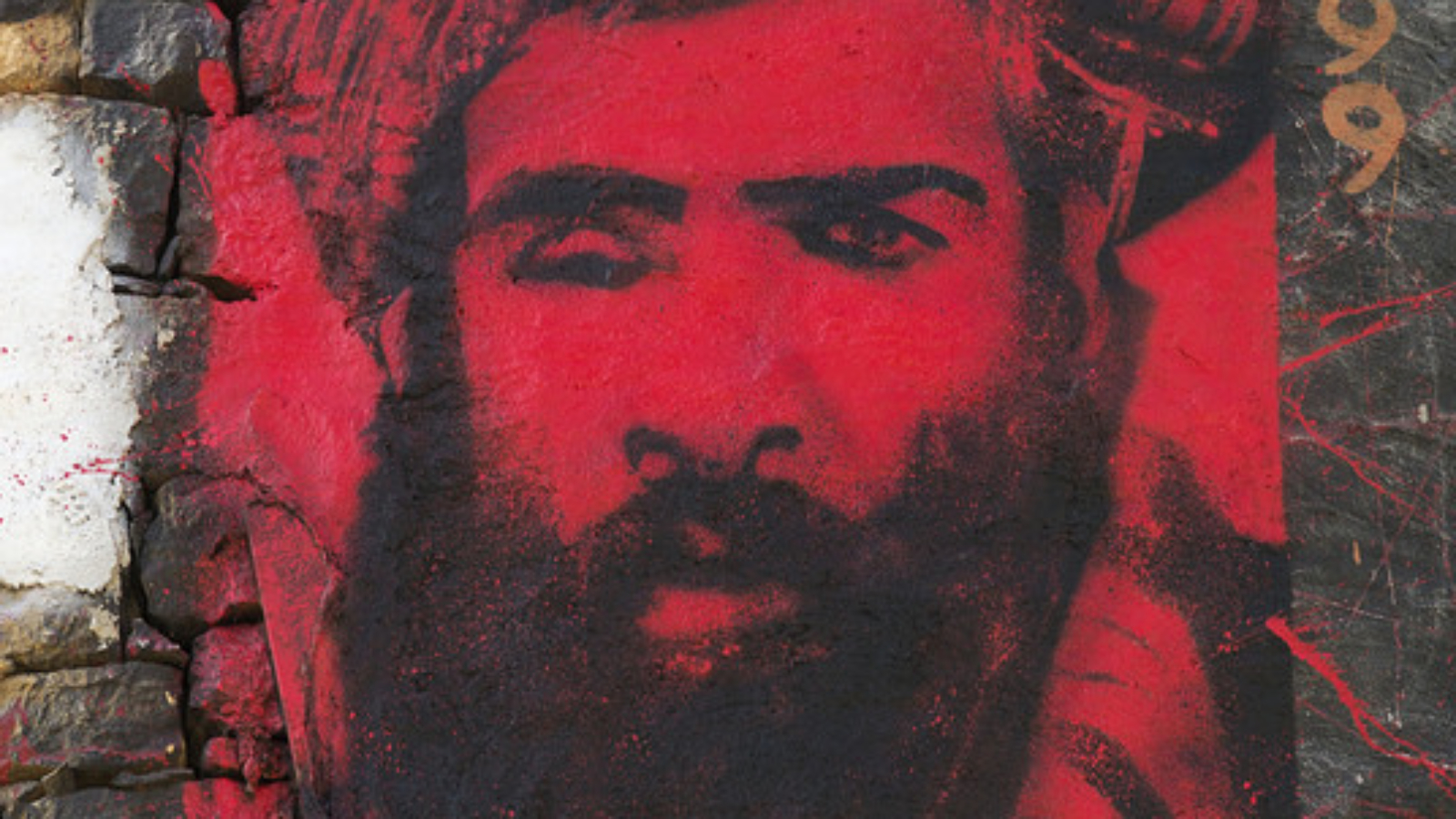

[Photo courtesy of Thierry Ehrmann]