From the Fall 2015 Issue “Food Fight“

By Jacques Myard

PARIS—On Feb. 25, during a trip to Syria with a French parliamentary delegation, I met with Bashar al-Assad. In the delegation with me were three other lawmakers, Socialist Gérard Bapt, center-right senator Jean-Pierre Vial, and centrist senator François Zocchetto. The result of this cross-party initiative was a huge public outcry in France. But it also served as a wake-up call to the ongoing Syrian tragedy, as well as French and, more broadly, Western policy toward Syria. President François Hollande, Prime Minister Manuel Valls, and Foreign Minister Luarent Fabius all voiced their consternation and disapproval.

Needless to say, the trip had not been approved by French authorities. Bapt, himself a member of Hollande’s ruling Socialist Party, was strongly advised by the Elysée presidential palace not to meet with Assad during the visit and wound up absenting himself from the event. I, for my part, neither expected to receive nor asked for a green light. Deputies are free to do as they wish. After all, parliamentary diplomacy can be a useful tool for democracy.

France had broken diplomatic ties with Syria in March 2012 and was one of the first countries to shut down its cultural institutions there. It also cut all its subsidies to schools, such as the French Lycée Charles de Gaulle in Damascus, which depended on this funding to survive. Since the opposition movement began fighting in March 2011, Syria has been in the grip of a paroxysm of violence, causing over 220,000 deaths and sending 3 million refugees fleeing to safety. But in spite of this civil war and its wave of atrocities, serious doubts about the relevance of France’s political conduct and the sudden rupture of our diplomatic relations with Syria have always existed and were at the root of our initiative.

Indeed, the resolution of the civil war in Syria may well hold the key to thwarting many of the most pernicious challenges to the world order—from the Islamic State to al-Qaida in the Levant—and bring many of the more traditionally hostile parties in the Middle East closer together.

WHERE’S BASHAR?

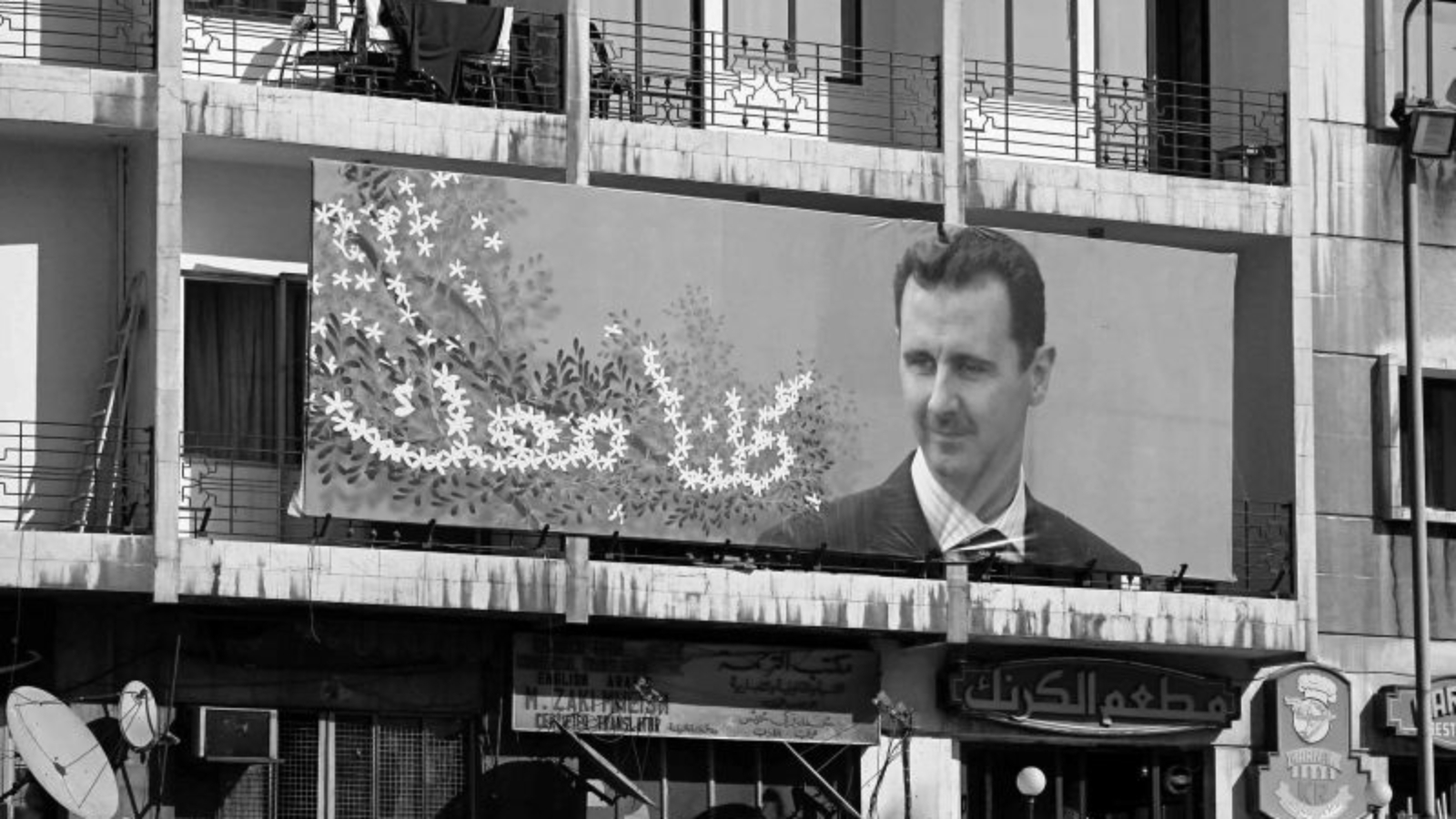

According to some predictions, Assad was supposed to disappear within 15 days of the start of the uprising against him. But he is still there, four years after the beginning of the rebellion against his rule. That intelligence failure was a product of a partial and superficial analysis, which expected the Arab Spring to blow through this country as it did across much of the region, sweeping every ancient regime before it. Such a perspective shows a total misunderstanding of the peculiar circumstances of Syria and its position at the heart of profound rival interests of a host of major powers. Moreover, the still ruling Alawite president benefits from the support of a large part of the Syrian population. During our encounter, he occasionally expressed himself with ease in French, and seemed to me neither feeble nor at all desperate—rather serene and a perfect master of his thoughts.

His supposedly moderate opponents in exile, supported at arm’s length by the West, cannot conceal their growing weakness on the ground and their endemic divisions. Faced with this stewpot of mediocrity, the jihadists of the Islamic State and the al-Nusra Front, a branch of al-Qaida in Syria, both radical Sunni groups on the UN’s list of terrorist organizations, are experiencing a rapid expansion. The Islamic State, in the regions it’s conquered, practices terror and destruction, committing all sorts of abuses, notably directed at Christian minorities—more than 200 Christian Assyrians were abducted in February, for example. But its violence is also carried out against other minorities and communities: Kurds, Shiites, and moderate Sunnis who have had the misfortune to oppose the forces of the Islamic State. The desire of these terrorist groups in the end is to impose Shariah law in the name of radical Islam.

We also know these groups’ ability to mobilize recruits in Europe, notably in France, whose citizens form one of the most important European contingents in the Syrian uprising. Bernard Cazeneuve, Minister of the Interior, announced the presence of more than 300 French recruits in Syria in the beginning of February—a number that has doubled today. Many return with the idea of inciting attacks on our own soil. Was it reasonable to cut off all sources of intelligence with Damascus?

It was clear, moreover, that the civil war doubled as a proxy war between regional powers. It is no longer possible to be satisfied with the simplistic attribution of all the deaths to the “butcher” of Damascus—even if it is incontestable that he bears at least part of the responsibility for the drama that his country is now enduring. It was thus our obligation to inform ourselves of the situation by going to Syria.

HISTORIC TIES

France has strong historical ties with this country. Interests in the protection of Christians in the East date back to Francis I, who in 1536 negotiated a landmark alliance with the Ottoman Empire, which at the time ruled all of what is today Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq. Furthermore, France exercised a mandate in Lebanon and Syria between the two world wars, from 1920 to 1946. It has close ties with the Syrian people, among them the Christian minorities who, until recently, lived in peace with the other communities on this land. In short, French cultural presence is the product of long and fruitful cooperation.

That said, I’m by no means defending the ruler of Damascus. It is clear that his is a police regime with blood on its hands. In the beginning of the revolution, it harshly repressed opposition demonstrations, notably in Daraa in the south. Despite the denials of Assad in the course of our interview and a report by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology on Jan. 14, 2014, the Assad regime was clearly responsible for the use of chemical weapons in August 2013 against civilians in the eastern quarters of the capital. Even if it is possible that this decision was made at a subordinate level, the regime crossed the red line fixed by the United States and the other Western powers before the latest agreement on the dismantling of the Syrian chemical arsenal was signed.

CONVERSATIONS

This is not about absolving Assad but about taking account of realities. He is still in power and still controls a large part of the country. So, in the course of our conversation, I seized the opportunity to remind the Syrian president that he still held a number of political prisoners, in particular his opponent Louaï Hussein, a human rights activist. While I am reluctant to claim any direct role, Hussein was freed the evening we left Beirut immediately following our visit to Syria.

Indeed, Assad was quite candid in his remarks to us. There will not be a military victory, he conceded, but rather all paths will pass through a political solution and “the winning back of hearts.” A number of our interlocutors underlined the risk that chaos will spread to other states in the region, touching Lebanon first if the Assad regime falls.

Apart from the Syrian president, I met with the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Wallid al-Moallem, the Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs, Ayman Soussan, and the President of the Parliament, Jihad Al-Laham. The Grand Mufti, Ahmad Badr Al-Din Hassoun, who is Sufi, and the Melkite and Greek Orthodox patriarchs whom I also met, view Damascus as the last and best rampart for the protection of Christians, in the absence of a credible Syrian opposition. The religious authorities had already warned me of the dangers of Islamist fundamentalism in mid-2010, during an earlier parliamentary mission I led to Syria. Even then, they felt radical Islam was growing in power, posing a great danger to the existence of any number of communities.

On my latest visit, I met the representative of the International Red Cross, and the admirable personnel of the French hospital of Damascus who try to heal wounds in the absence of key drugs and medical equipment. I witnessed the devotion of teachers at the Lycée Charles de Gaulle, and the bravery of 250 pupils who continue to study and learn despite the rocket fire and hardship of war and despite the French government funding cuts.

BLINDA DOGMA?

It is clear that ours is a policy of blindness, while the dogmatic intransigence of our diplomacy is raising more and more questions among the French people and across Europe. At the same time, all efforts to settle the conflict drag on without resolution.

So not surprisingly, the Islamic State, the Sunni caliphate proclaimed by its leader Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi in Syria and Iraq in June 2004, is progressing, with its string of bombardments, continued seizure of territory, and acts of violence against civilians. Since it seized the ancient city of Palmyra, the jewels of Syria’s patrimony and the global heritage of humanity are in danger. It is erasing the diversity of cultures, the memory of peoples, and the traces of all that is contrary to its reactionary ideology, which is seeking to return the world to a period a thousand years in the past. This organization has succeeded in consolidating its base thanks to the abundant resources that rest on the collecting of taxes in controlled zones, human trafficking, and the sale of contraband hydrocarbons and works of art. And while many of its most recent territorial conquests may be in Iraq, where the West has continued to focus its military response, its head and heart remain in Syria—and portions of the country all but out of reach to the forces of Assad.

The deterioration of the situation is a cruel illustration of the helplessness of what we conveniently call “the international community” and of France. Forced to admit the “continuing degradation” of the situation as demonstrated by the Islamic State seizure of Palmyra in Syria and Ramadi in the province of Anbar in Iraq, despite strikes by the international coalition, Paris convened a conference on June 2 to fight against Daesh, another name for the Islamic State. It welcomed some 20 ministers and international organizations, and the Iraqi President Haïder al-Abadi made the trip. Sadly, the talks focused entirely on Iraq.

Fabius reaffirmed his “total determination” to fight the Islamic State. A certain number of decisions had been taken without calling into question the logic of the airstrikes. Concerning Iraq, it’s a question of reinforcing the support of Sunni tribes, creating local authorities, and reinforcing the funds for stabilization of populations managed by the UN. With regard to Syria, the aim is to accelerate the process of political transition, finally reactivating the Geneva process that was never completed.

WRONG WAR & NATION

Unfortunately, French and most European diplomacy are running into two pitfalls. The first consists of dismissing key actors in the fight against radical Islamist groups, namely Iran, Russia, and the Syrian Kurds. The second is refusing to do away with some key ambiguities. Some of France’s allies—Turkey, certain Arab states in the Persian Gulf—and France itself beginning in 2012, ventured in secret and despite the EU’s embargo, to deliver arms to insurgents. We could only guess too well whose hands they would fall into—al-Nusra, the aforementioned al-Qaida affiliate.

Soon after my return to Paris on March 1, I learned that the Hazem movement had dissolved. An alliance of several supposedly moderate Islamist elements armed by the United States, the majority of their fighters joined determinedly jihadist groups, bringing with them the most modern equipment available, including 80 Tow anti-tank missiles.

Taking reality into account means that we must work for a political solution, as there will not be a military one. The first task is to consider that we were wrong about the enemy and to realize that jihadist forces are enemy number one. After that, we must engage in dialogue with all the actors who are part of resolving this conflict.

First, we must open a channel to Assad. Diplomacy is the art of talking with everyone in the world, even one’s enemies, and it must maintain a pragmatic tone. Our country did just that in the fight against Adolf Hitler when we allied ourselves with Joseph Stalin, who had massacred Polish officers in Katyn and millions of his own people in his march to power. Equally, we reached an agreement with the National Liberation Front (FLN) in Algeria to end that war against French forces.

Now, the Syrian president is part of the solution. There is no way around the fact that we must negotiate with Assad and not demand his expulsion from power as a precondition for any talks, as U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry and UN mediator Staffan de Mistura reiterated on March 15. Such declarations only constitute a blow to our diplomacy. This should be taken even more seriously since the Syrian president can count on the support of Iran—and Hezbollah fighters—as well as Vladimir Putin’s Russia. It’s under Russian leadership that a dialogue between the Damascus regime and certain elements of the internal opposition is being held.

It is by no means in our interest to cut all ties with the regime. This would be depriving ourselves of an important tool in the prevention of and fight against terrorism. At least some Americans, who may be questionable in many respects, have the pragmatic sense to understand the interest in maintaining contact with Damascus. I had the occasion on my trip to speak with former U.S. attorney general Ramsey Clark who has found himself frequently these days in Damascus, though absent any official American diplomatic portfolio.

We must avoid at all costs giving the impression that Western leaders can still pull strings and impose on other governments whatever they wish. The very principles on which Western democracies are founded lose credibility and are weakened on the ground when they encourage an exiled opposition like the Syrian National Council, some of whose members have not set foot in Syria in 20 years. Such a government-in-exile has been worn away by divisions that explain the quick rotation of its president and exploitation by regional powers. Indeed, a former leader of the Council, Ahmad Jarba, is a businessman with close ties to Saudi Arabia.

PUBLIC ENEMY NUMBER ONE

Making the Islamic State the enemy of highest priority implies terminating all sources of support that could benefit this barbaric organization. It means ending our silence and denouncing the duplicity of certain states in the region who play the sorcerer’s apprentice to knock down Damascus and oppose Iran. In fact, we are playing a veritable game of liar’s poker in Syria with all the key powers in the region. In a game of complex, sometimes unpredictable alliances, each regional actor is trying to advance its own pawn.

While denying it’s provided any support to jihadist groups, Turkey is playing a very troubling game. The Turkish President, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, sees himself as a new sultan. His dream is to recreate a grand caliphate from Turkey to North Africa with his Muslim brothers, an ambition that is undermined by Egyptian strongman Abdel Fattah el-Sissi in Egypt and Tunisian President Beji Caid Essebsi.

Indeed, and somewhat hypocritically, Turkey buys large quantities of oil from the Islamic State, quite blatantly flouting the embargo, while the porous borders they share are open to all kinds of trafficking—arms, antiquities, and fighters who come to support the Islamists. A border check at the beginning of the year of an important convoy of Turkish trucks revealed a sizable load of arms and explosives destined for jihadist groups.

We must also take into account Sunni-dominated Saudi Arabia, which has embarked on a merciless war of influence against Shiite Iran—the bitter intra-religion rivalry that doubles as a traditional power game. Saudi Arabia still feels threatened by their fellow Sunnis of the Islamic State. In the face of these dynamics, Saudi Arabia, the birthplace of its own brand of extreme Sunnism, known as Wahhabism, and Qatar, refuge of the Muslim Brotherhood, can set their rivalry aside to support and finance radical movements. Doha, of course, can count on its powerful media outlet, Al Jazeera, to broadcast the declarations of high-ranking al-Qaida members, providing it some protection from the depredations of terrorists who are anxious to have a reliable media outlet on the global stage.

Back in May, in an interview on Al Jazeera, the leader of the al-Nusra Front in Syria declared his ambition to impose Shariah law across Syria. As for Israel, many observers in the region claim that the country is providing the al-Nusra Front with weapons in the Golan Heights to fight its bête noire, Hezbollah. Jordan, caught in the middle, is also allowing arms to cross its borders. In short, a complex, often lethal kaleidoscope of interests and alliances is revealing itself across the region.

The question now is whether France and other Western countries will be capable of putting an end to their contradictions and clearly target the real enemy—the Islamic State and its affiliates. Our diplomacy must address this challenge, and in doing so, it must include all parties that have a role to play in resolving the conflict. This includes Russia and Iran, which must both be considered partners in the balance of the region.

In short, it is urgent that we change our foreign policy. The breakup of Syria and the subsequent spread of chaos to neighboring countries, the establishment of a regime that is subjugated to the Islamists, the continuation of fighting with its ongoing parade of horrors, and the deepening of the humanitarian crisis are scenarios that must be prevented at all costs. As the great 17th century French theologian Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet warned us, we cannot lament the consequences that loom ahead while cherishing the causes. In today’s world, that would translate to fearing the disintegration of the Syrian nation, while supporting the foundations of the Islamic State and the extension of the al-Nusra Front.

*****

*****

Jacques Myard, a Republican member of France’s National Assembly, serves on the Parliament’s Committee of Foreign Affairs.

[Photo courtesy of Watchsmart]