By Devyn Spence Benson

HAVANA—“The black race has always been very oppressed and now is the time for them to give us justice, now is the time for them to give us equal opportunities to live,” Cristobalina Sardinas—a resident of Las Yaguas, one of Havana’s poorest slums—asserted three weeks after Fidel Castro’s 26th of July Movement (M-26-7) forces ousted U.S.-backed Cuban President Fulgencio Batista. In January 1959, the new government’s young leaders were about to embark on a set of social reforms and policy changes that would make the Caribbean’s most populous nation beloved and admired by some and hated and maligned by others for decades to come.

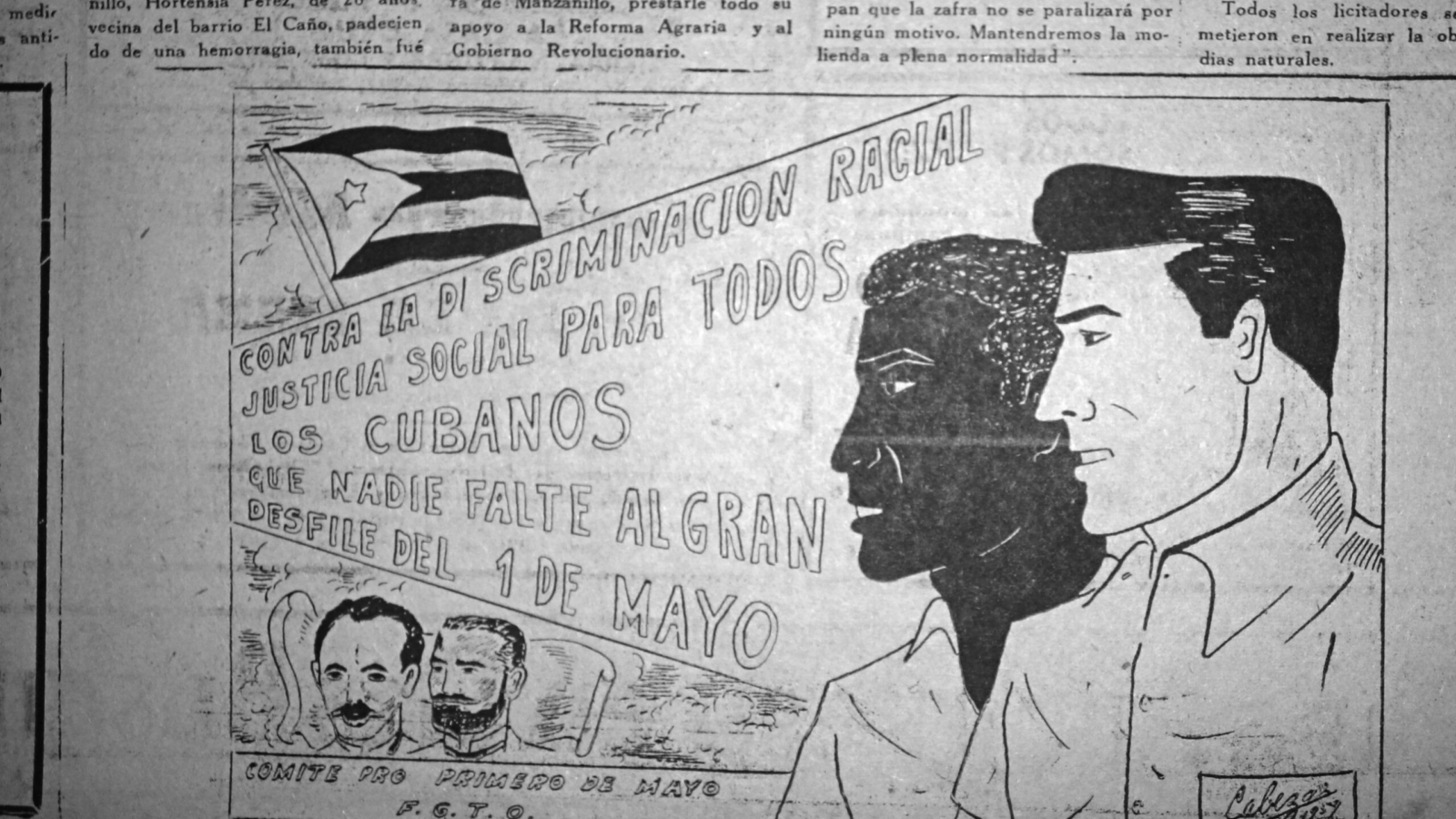

The new government passed over 1,500 pieces of legislation during its first 30 months in power, including laws delivering land redistribution, free health care, and educational scholarship programs. Added to these reforms, in March 1959, Castro announced a public anti-discrimination campaign that promised to fulfill late 19th-century aspirations to build a raceless and unified Cuba. National headlines outlined plans for integrating previously whites-only spaces—especially private schools, beaches, and recreational facilities—and providing employment and educational opportunities to Cuba’s most marginalized citizens. These changes created unprecedented social opportunities for blacks and mulatos (mixed race Cubans) in the ensuing decades and had lasting effects on Afro-Cuban lives. By the 1980s, black and mulato Cubans had virtually the same life expectancy, high school education rates, and percentage of professional positions as white Cubans—in sharp contrast to the United States and Brazil where significant disparities existed between whites and blacks in each of these markers of equality. Today, large numbers of Afro-Cuban professors, doctors, and other professionals (working in racially integrated public spaces) attest to the ways revolutionary actions brought about change and opened doors for Cuba’s citizens of African descent.

Yet, Cuba’s 1959 campaign against discrimination, which officially ended in 1961, was a program full of contradictions, consisting both of real social change and national myth-making about a government’s, even a revolutionary government’s, ability to eliminate racism in only three years. The title of the January 1959 article in the M-26-7 official newspaper, Revolución, that featured Sardinas—“¡Negros No … Ciudadanos!” or “Not Blacks, but Citizens”—foreshadowed the government approach. Although M-26-7’s anti-racist program provided many of the tangible social reforms that Afro-Cubans like Sardinas had expected, the new Cuban government’s attitude toward blackness was ambivalent and unstable, and left little space for Afro-Cubans to be both black and citizens. Building on 19th-century discourses that imagined Cuba as a raceless space of “not blacks, not whites, only Cubans,” the article’s title suggested that residents of neighborhoods like Las Yaguas had to discard their poverty and their blackness to join the revolution. This was and remains a false dichotomy for many Cubans of color.

In January 1959, Sardinas expressed her frustrations with previous administrations and her expectations for the new government as a black person, a Cuban, and a woman. She felt entitled to certain rights, like other citizens, and was aware and proud of her blackness. While some Cubans of color agreed with the revolution’s raceless sentiments, others used the state rhetoric to demand additional reforms. And a third group found the image of revolutionary nationalism without blackness unsettling and paternalistic, and looked for ways to lead organizations that recognized both their blackness and Cubanness. In the end, just like the irony of titling an article about black demands, “Not Blacks, but Citizens,” 1959 revolutionary promises of equality and national integration programs sat alongside inconsistent state rhetoric that allowed racism to continue and infiltrate Cuban ideologies in subtle, but lasting, ways.

Read the full article in our spring 2016 issue

* * *

* * *

Devyn Spence Benson is an assistant professor of history and African and African-American studies at Louisiana State University and the author of Antiracism in Cuba: The Unfinished Revolution (UNC Press, 2016).

[Photo courtesy of Oriente]