Hans Block and Moritz Riesewieck are the creators of The Cleaners, a documentary that focuses on the content moderation and censorship that aims to keep social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter free of violent, pornographic, or hateful content. Their research takes them to the Philippines, where they meet the Facebook employees who conduct the filtering—the majority of whom are bound by non-disclosure agreements—and explore the effects of being privy to the extremes of the internet. World Policy Journal spoke with Block and Riesewieck about the film, which was featured this year at the Human Rights Watch Film Festival in New York, and the questions it posits about the world of social media: Who is in the most legitimate position to decide what we see? And are the tech giants that dominate this field really as transparent as they claim to be?

WORLD POLICY JOURNAL: How did the idea for the film come about?

HANS BLOCK: One starting point for the film is a video on Facebook that was circulating on March 23, 2013. The video, without getting into too much detail, depicted rape and child abuse. It had run rampant on social media and by the time Facebook deleted it, it had already accumulated over 4,000 shares and countless more reactions. We asked ourselves, “Why is this happening?” We knew that the internet contained all sorts of uncomfortable material, but we were curious about the management of such content on social media sites. So, we started researching algorithms and artificial intelligence, which led us to Dr. Sarah T. Roberts, an expert on content moderation. She told us that actual people are behind the filtering, and in most cases these jobs are outsourced to developing countries. Naturally, we wanted to get in touch with the workers doing these kinds of jobs; we thought it’d be interesting to humanize this on several different levels. On one level, content moderation must be a very stressful job; on another level, these young people are deciding what the world gets to see. We learned quickly that a part of this industry, based in Manila, in the Philippines, is very secretive and very hidden.

WPJ: I recall the film revealing that many of the employees are bound by non-disclosure agreements and were afraid to speak out and reveal their opinions and or experiences conducting social-media filtration. How did you get in touch with them given these challenges?

MORITZ RIESEWIECK: That was the hardest part of the entire process. The companies did everything they could to keep the work secret, to keep it under the radar. For example, code names existed within the industry to hide the companies’ identities. Facebook is called the “honeybadger project.” The workers are never allowed to disclose that they’re working for Facebook; they have to say “I’m working on the honeybadger project.” What’s more, they’re at risk of losing their jobs if they violate the non-disclosure agreements. We also learned that there are private-security firms that pressure the workers not to talk to strangers at all, encouraging them to keep their socializing to a minimum. These firms also scan the social-media accounts of the workers themselves.

HB: It took us quite a while … we had to act like detectives, piecing together different pieces of a larger story. Some locals guided us and helped our research. We had to win their trust and work with many of them very closely.

MR: What’s also interesting is how proud some of the workers felt about their duty. They would tell us that, without them at the helm, social media would be a complete mess. That being said, many of them suffer silently from the impact the work has on their health and mental wellbeing.

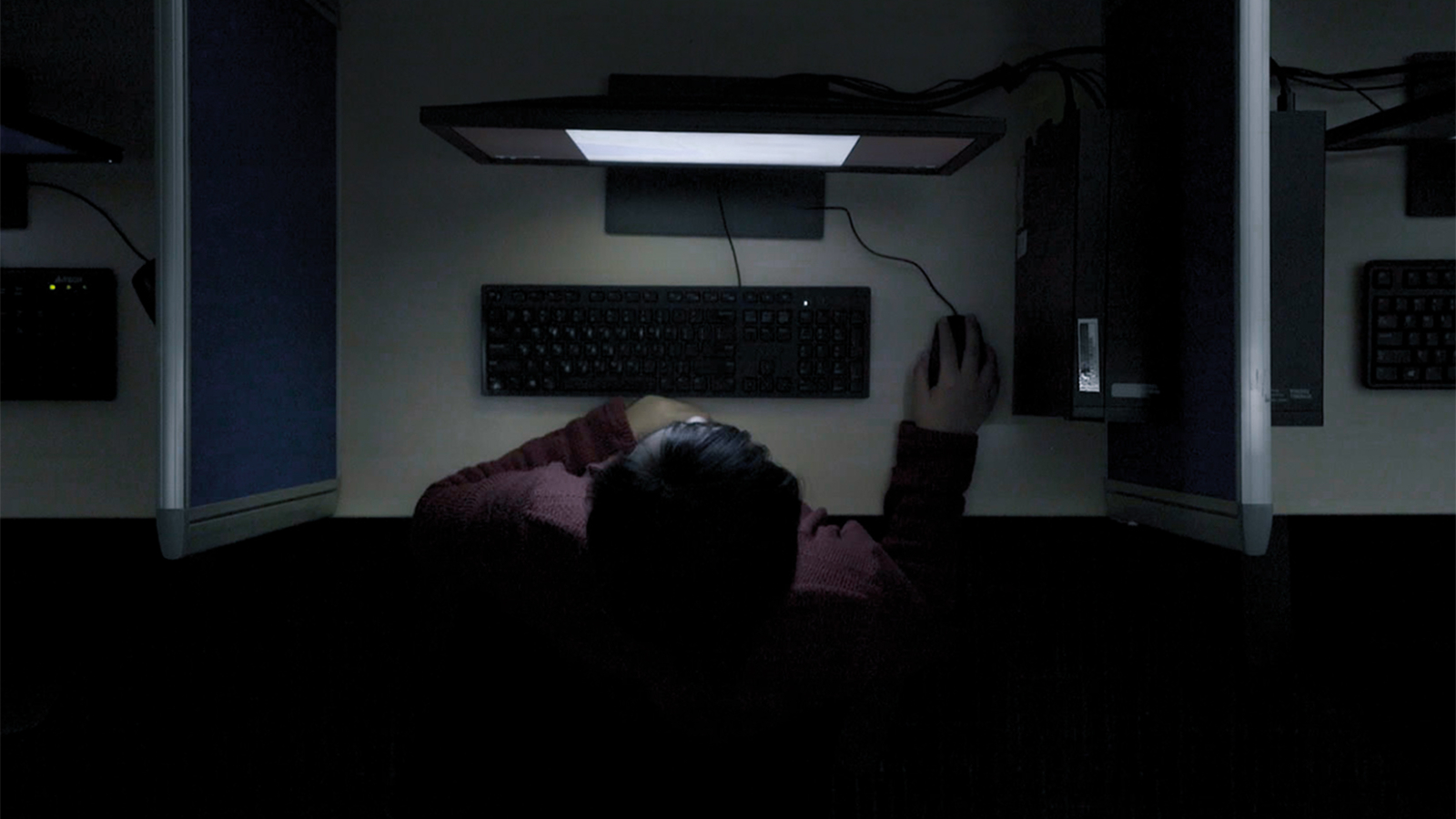

WPJ: Visually speaking, the eerie, neon-lit, almost film-noir portrayal of Manila metaphorically mirrors the psychological isolation of the subjects. Was this always an objective of yours, or did the style of the film develop once you were there?

HB: It was an interesting place: A city of that size, consisting of 18 million people, still often felt dark and disconnected. We were often more active at night because it would be daytime in the U.S., so naturally this is when social media is most active, when the Western Hemisphere is using it. So these workers are at the top of their game at night, and that, I think, informs the theme and cinematography of the film as a whole.

WPJ: What’s been the reaction from Silicon Valley? Have any of these companies issued statements or reacted publicly to the film?

MR: Hans and I were interested in including them from the start. We didn’t mean for the film to set up an opposition; actually, we wrote to Facebook and a few other companies asking if they wanted to submit a statement, or some kind of reaction that we’d be able to put into the film, but we never received any replies. The lack of their presence within the film is not because we didn’t want them to be there.

HB: It communicates that, despite what [Facebook CEO Mark] Zuckerberg and co. say, these companies are really not as transparent as they seem. When a social-media site becomes more or less a digital public sphere, it’s problematic, because it makes you realize that this is no longer a forum where you post cat videos; instead, all sorts of material is being shared. Companies like Facebook really should be speaking up, addressing these problems, and shedding more light on how they filter their own networks.

WPJ: What kind of conversations need to be had on a public level?

HB: The issue is that the companies don’t believe a public debate is necessary right now. A month after the film came out, Mark Zuckerberg announced Facebook would be hiring 20,000 more people to conduct content moderation work. But that doesn’t sound like the best fix; Facebook could hire thousands more people, but there is an underlying lack of transparency and lack of responsibility. To restate my earlier point, these companies only want to shed light on their secret practices when absolutely necessary; they don’t think it’s worth a public conversation.

MR: One more anecdote I’ll add: We had a public screening of The Cleaners a couple of days after a Facebook keynote, and a couple of Facebook employees were at the show. They came up to us after the film concluded and admitted they were really, really shocked. We exchanged contact information, as they said they’d be interested in arranging a screening in the offices of Facebook itself. We were happy with this conversation and, after a week, reached out to them. But in that case, just like Facebook’s behavior earlier, we were left with complete silence and no responses.

WPJ: If there’s one thing you could say to the social media companies, what would it be?

MR: Do not be surprised if you continue to see “fake news” and controversial content. Do not be surprised if these “extremes” continue to pop up—all this is innate to the business model of the companies in question. The companies tell you that their platforms are being “abused,” but in truth, the architecture lends itself favorably to scandal-based content, and this is starting to overwhelm the workers in the Philippines and around the world. Zuckerberg also needs to hire well-educated journalists to do the cleaning work: The young Filipinos sitting in front of a screen thousands of miles away with little knowledge of the subjects they’re moderating could be dictating what ends up on the front page of the Guardian or the New York Times.

HB: The notion that technology and social media are “neutral’ can be debunked. The architecture of social-media networks and the algorithms used are programmed in a very specific way. Every “extreme” form of content leads to clicks, likes, and views. That’s exactly what the platforms want: The more audience engagement they have, the more feasible it is to convert this activity to something monetary, something profitable. That’s the status quo of our digital world, and it needs to be changed.

* * *

* * *

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

[Images from The Cleaners courtesy of Hans Block & Moritz Riesewieck] [Interview conducted by Shahid Mahdi]