By George F. Paik

At the root of most of the conflicts confronting the world today are nationalist claims of dissatisfied groups. From Catalans, Kurds, and Scots to the so-called Islamic State to Trump, Brexit, and Le Pen voters, these actors assert the interests of dormant, oppressed, or newly configured national identities. Russia’s and China’s governments invoke national roots to consolidate internal rule and international roles. Information technology helps mobilize nationalisms, reaching people who have increasing time and resources to explore, define, and act on their affinities.

Almost all of these movements oppose liberal states, institutions, or influence. They have not coalesced around a vision of illiberal global norms, but the potential should raise concerns.

Most nationalisms are based on traditional markers: ethnicity, religion, territory, folkways, or dynastic history. Those elements give group members a sense of solidarity, which helps nations survive and compete. But tradition-based nations confront two major problems. First, any traditional identity rests on some founding myth, and modern, science-based thinking invariably dilutes its sway. Second, such societies cannot really have common interests; they define themselves as different from each other. War, therefore, is a perennial possibility. Furthermore, after millennia of war, many nations contain defeated nationalities. Individuals now have the means and inclination to unearth ancient identities, which revives potential conflicts where civic peace once held.

One response to the risk of perpetual war has been to find universal rules to govern sovereign entities. Socialism was the most prominent attempt in recent history. Led by Soviet communism, though, it took an oppressive form, and failed. China, until the 19th century, promulgated Confucian norms across Asia. This ethos, though, was a tool for one nation’s dominance, and with China’s weakening at the hands of the West, the ethos fell with its Chinese vessel. The Islamic State claimed the universal authority of the Ummah, but like China’s system, that could only serve one identity. A nascent global environmentalism invokes everyone’s interest in ecological preservation, and follows scientific analysis rather than vested interests, but any political basis for governance remains far off.

A more liberal response has been to establish supranational authorities. The EU regulates national interests in Europe for the sake of peace and prosperity, driven by the traumas of 20th-century wars. The U.N. also aspires to international authority. Ultimately, these entities depend on all members compromising their traditional sovereignty. But if they exercise power too heavily, they risk abandonment, à la Brexit. Conversely, if they fail to keep order, they die like the League of Nations.

This conundrum is endemic and particular to liberalism. While other “isms” ordain truth, liberalism defers to individuals to define their own norms and rules, so liberal government requires consent of the governed. It renounces oppression and is theoretically universal, but is weakened in governing authority, making it vulnerable to both disorder among its constituents and abuse by those in power.

Advocates of illiberal groups make the political argument that, despite liberals’ professions of impartial, abstract, universal principles, the Western nations that incubated this ethos all too frequently cite those values as they transgress on others’ sovereignty, dominate resources, and undermine order in other countries. Russia, China, the Islamic State, and others see liberalism’s influence as merely a vestment of Western hegemony—one more ideology used to dominate the world, differing from the Islamic State’s jihadism or ancient Chinese Confucianism only in its craven success.

Leaders of illiberal regimes must also contest liberalism philosophically because the moral force of democracy, equality, civil liberties, and individual fulfillment undermines their rule. These leaders advance the argument that people are amoral, selfish beings that need external authority to be kept in order. They cite Western sexual mores, financial scandals, crime, and populist protests as evidence.

Liberal analyses instead see these examples as dislocations that come with change, disorders resulting from bad events, or statistical outliers. Liberals value the “disorderly” human impulses that act as catalysts for new understandings, new technologies, and new exchanges. The universal recognition of these impulses, and their value, helps explain the spread of liberalism to diverse parts of the world.

The task set for liberals is not to defeat illiberal nationalisms. Trying only corroborates Russian and Chinese claims against them; even seeking political compromise is to enter the same game of competing ideologies. The liberal challenge is, rather, to demonstrate the benefits of liberating the full potential of human nature, to avoid undermining other nations’ development, and to practice realpolitik only in sincere defense. People, as liberals believe, will be free.

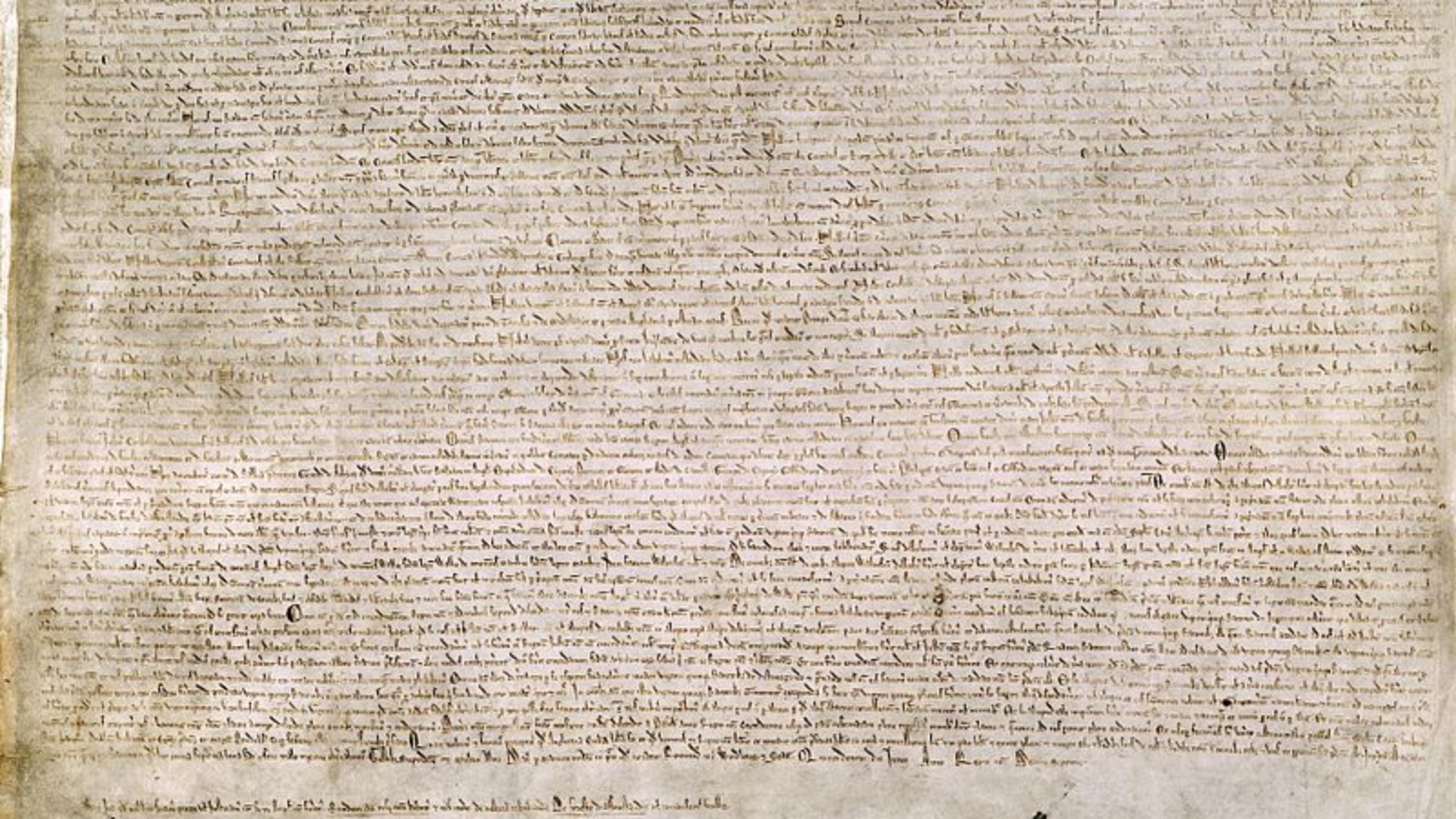

Liberalism’s fate is tied to the conduct of the United States. In its Declaration of Independence, the U.S. established a rare non-traditional nationalism, based on the abstract principle of “unalienable rights” and government existing to “secure those rights.” Even the engrained liberalism of the United Kingdom evolved over centuries as a national trait, from the Magna Carta to the English Civil War and onward. The United States’ nationality was created from whole cloth, on nothing but the tenets of liberalism. If the country neglects these principles, it undermines its own nationality. But if the U.S. embodies its founding premise, it bolsters liberalism’s case.

New communications channels alert everyone around the world to the tension between traditional identities and liberal doctrine. Nationalisms can develop either into greater liberalism, as in modern Germany, or away from it, as in Russia and Hungary. New, old, or revived nationalities could devalue liberal ideals, should they follow the latter direction. Liberal societies that protect freedom and show its merits through their own conduct are best positioned to inspire others to value individual rights.

* * *

* * *

George F. Paik is a former political affairs officer in the U.S. Foreign Service and a U.S. capital markets veteran. His diplomatic career straddled the end of the Cold War, in Washington and at postings in Brazil and in Trinidad and Tobago. Paik holds a BA in Social Studies from Harvard and an MBA in Finance from Wharton.

[Photo courtesy of Earthsound]