From the Fall 2015 Issue “Food Fight“

By Andrei Soldatov and Irina Borogan

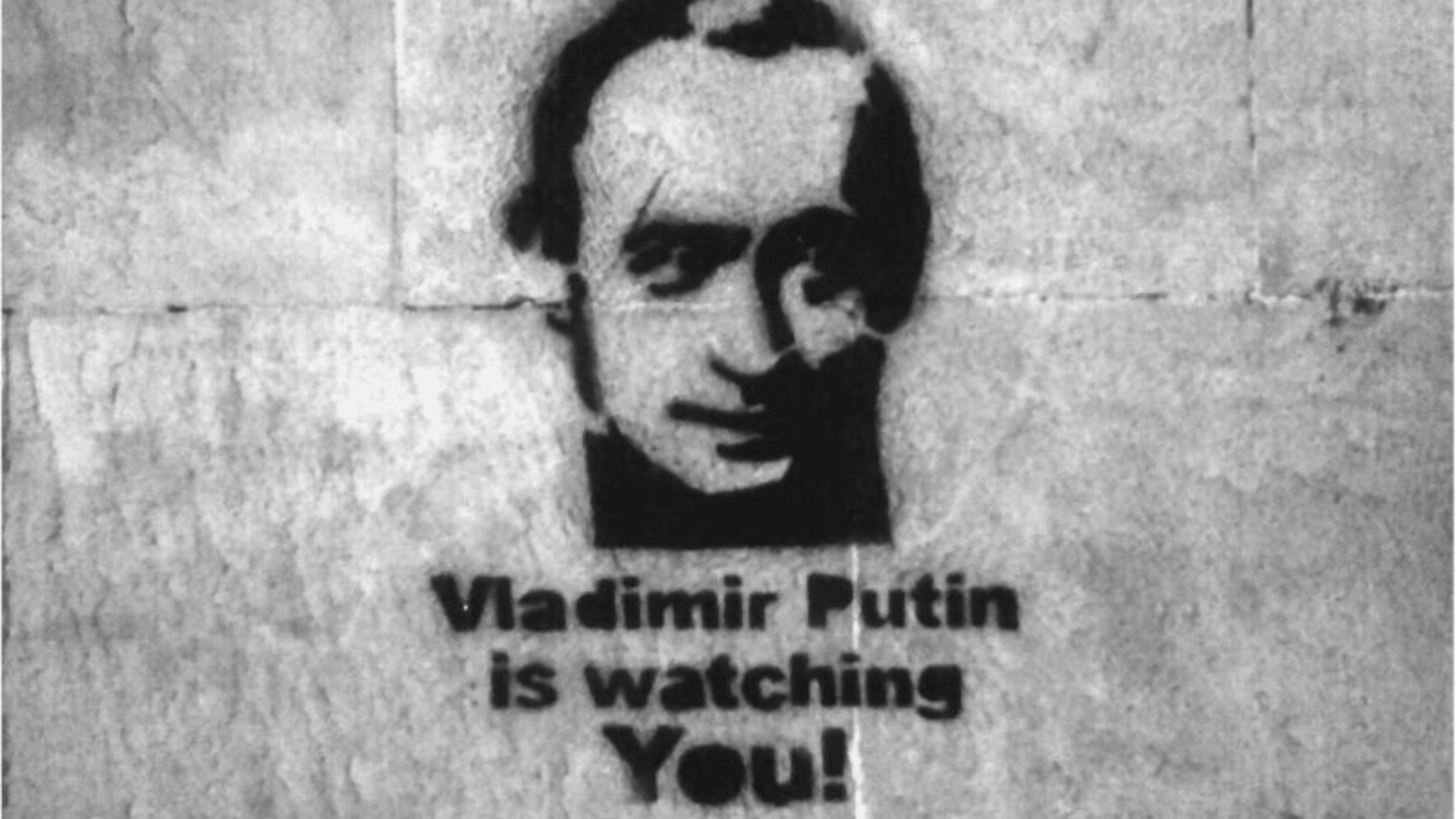

MOSCOW—The Kremlin launched a massive offensive on the Internet three years ago after protests swept Moscow following President Vladimir Putin’s return to power. Since then, the RusNet (Russian segment of the Internet) has been coping with blacklists of banned websites and a nationwide Internet filtering system. In 2014, the annexation of Crimea only reinforced the Kremlin’s paranoia and increased the fears of a free flow of information that could pose “a threat to stability,” or more specifically, to the dominance and control of Putin himself.

With independent news media blocked, Putin then came after local social platforms and Russian bloggers. Now it is time for global platforms like Google, Twitter, and Facebook. The Kremlin wants them to relocate their servers to Russia, if they want to continue to serve the domestic market. But whether or not they comply with the Kremlin, in the long run, the Kremlin’s strategy to bring the Internet to heel can’t work—though its efforts may be profoundly unsettling, at least in the near-term.

WEB UNRESTRICTED

The web, decentralized by design, is made for unrestricted information exchange. And the crisis in Ukraine already showed how accessibility of the network can undermine the Kremlin’s efforts to control information.

On March 18, 2014, Putin convened the two houses of the Russian Parliament in Georgievsky Hall, the largest and grandest hall in the Kremlin Palace. Decorated in white and gold, the Hall honors the military order of Saint George. The colors of the order—yellow and black—representing the fire and gunpowder of war, or the death and resurrection of Saint George, are the colors of the original Russian imperial coat of arms (black eagle on a golden background). In the months to come, they were also to become the symbol of pro-Russian militants in Ukraine.

Putin gathered the deputies to celebrate the taking of Crimea from Ukraine. He spoke emotionally about the destiny of Russia, interrupted by standing applause. Finally, he turned to the West, noting that Russia’s actions had already drawn threats of sanctions that might cause disruption inside Russia. He asked ominously, “I would like to know what it is they have in mind exactly—action by the fifth column, this disparate bunch of ‘national traitors,’ or are they hoping to put us in a worsening social and economic situation so as to provoke public discontent?” He promised to “respond accordingly.”

For the two weeks prior to Putin’s speech the Russian authorities had been making sure the opposition would get the point. The Internet was first to come under attack, the government beginning with social networks. On March 3, Roskomnadzor, the federal agency supervising communications and media, rushed to block 13 pages of groups linked to the Ukrainian protest movement on Vkontakte, or vk.com, the Russian version of Facebook. Then, a week before Putin’s Crimea speech, on March 13, three independent opposition new media—Kasparov.ru, Ej.ru, and Grani.ru—along with Alexei Navalny’s blog on LiveJournal were blocked. Notably, Garry Kasparov, the Russian world chess champion, has put himself forward as a future opposition candidate for President, and Navalny, a lawyer and political activist, has battled Kremlin corruption and organized two large anti-Putin demonstrations. The fourth independent new media, Lenta.Ru, was effectively self-cleansed by its owner, an oligarch loyal to the Kremlin. Lenta.Ru received a warning from Roskomnadzor because of critical coverage of events in Crimea—the editor was summoned and told to fire a reporter. When the editor refused, she was in turn fired, and the entire editorial staff walked out the door in protest.

Simultaneously, pro-Kremlin activists launched a website on the domain Predatel.net, where predatel means traitor, and domain extension .net for nyet, or no—no traitors. The site lists the public statements of liberals deemed unpatriotic. The first name on the list was Navalny, and it also included the opposition leader Boris Nemtsov. The website’s goal was to form the list of “national traitors”—terminology later evoked in Putin’s Crimea speech in Georgievsky Hall.

BACK TO THE FUTURE

The system of Internet censorship had been tested by authorities since the summer of 2012 (as we described in World Policy Journal’s fall issue of 2013). Now, thanks to the crisis in Ukraine, it was ready to be fully deployed in a smooth and decisive move. By the spring of 2014, the country had four official blacklists of banned websites and pages: the first to deal with sites deemed extremist; the second for sites blocked because of child pornography, suicide, and drugs; the third with copyright problems; and the fourth, launched in February 2014, lists the sites blocked without a court order because they call for non-sanctioned protests. In other words, they comprised Putin’s enemies list. Navalny’s blog, Ej.ru, Kasparov.ru, and Grani.ru were put in this last, fourth black list. Ostensibly, it was introduced to act in an emergency—when the riots erupt in the streets, and there is a need for the authorities to block information about the riots as quickly as possible. There were no riots on the Moscow streets in March 2014, and journalists of the blocked sites were issuing no calls to take to the streets. But that didn’t bother the authorities. When they were asked in court to provide examples of articles containing such calls to action, the response was simple—the entire content of the sites was problematic.

With the most prominent independent online media effectively blocked or cleansed, the authorities turned their attention to national online platforms. Russia is one of the few countries where domestic Internet brands are stronger than global ones—especially the Russian replica of Facebook, Vkontakte, and the search engine Yandex.

Some 13 Ukrainian groups posting on Vkontakte were blocked in March, but it was not enough for Russian secret services. On April 16, Pavel Durov, the 29-year old charismatic founder of Vkontakte, posted two messages on his page, bitterly lamenting the situation inside the company. The first was posted at 9:36 p.m.:

“On December 13, 2013 the FSB requested us to hand over the personal data of organizers of the Euromaidan groups. Our response was and is a categorical ‘No.’ Russian jurisdiction cannot include our Ukrainian users of Vkontakte. Delivery of personal data of Ukrainians to Russian authorities would have been not only illegal, but treason for those millions of Ukrainians who trust us. In the process, I sacrificed a lot. I sold my share in the company. Since December 2013, I have had no property, but I have a clear conscience and ideals I’m ready to defend.”

He then posted a scan of the FSB letter. The second posting, two hours later, declared:

“On March 13, 2014 the Prosecutor office requested me to close down the anticorruption group of Alexei Navalny. I didn’t close this group in December 2011, and certainly I did not close it now. In recent weeks, I was under pressure from different angles. We managed to gain over a month, but it’s time to state—neither myself, nor my team are going to conduct political censorship. . .Freedom of information is the inalienable right of the post-industrial society.”

On April 21, Durov was fired as chief executive of Vkontakte, the company which by then was under control of two oligarchs loyal to the Kremlin (Durov had sold his 12 percent share early in the year). Durov learned the news of his ouster from journalists. The next day, TechCrunch, a major technology website, asked Durov in an email about his future plans. “I’m out of Russia and have no plans to go back,” he responded. With Durov gone, the company was placed firmly under control of the government. Soon Durov was replaced as CEO by Boris Dobrodeyev—a scion of the post-Soviet media establishment. His father, Oleg, is head of the television colossus known as the All-Russia State Television and Radio Broadcasting Company.

MOVING HOME

In three days, it was Yandex’s turn—Russia’s largest search engine, which has some 60 percent market share within Russia. On April 24, Putin was in St. Petersburg at a media forum organized by the All-Russia People’s Front, an ultrapatriotic, populist movement Putin had urgently launched two years before when the United Russia Party had lost all its credibility. The new People’s Front, consciously evoking symbols and names of the Soviet era, had a modern political purpose for Putin—to counter the liberal-minded, Westernized intelligentsia of the big cities.

It was a staged event in the round, and in the middle of the discussion a pro-Kremlin blogger addressed Putin with a question about the Internet. First attacking the United States—“It is an open secret that the United States controls the Internet”—he then went after Google specifically. “Why can’t they build servers here?” he said, echoing the Kremlin line. “I do not want my personal data and information about politicians that run my country to go to the United States.”

To that, Putin replied that the Internet began “as a special CIA project. And this is the way it is developing.” But he didn’t stop there. Answering a second question from a blogger, Putin charged that Yandex, when it was formed, had been “forced” to accept Americans and Europeans in its company’s management. “And they had to agree to this,” Putin added. He also lamented that the company was partially registered abroad. Then Putin bore down on the real culprit he had in mind: “As I have said, this was all created by the Americans, and they want to retain their monopoly.”

The next day, shares in Yandex NV, the Dutch-registered parent company of Russia’s search giant, fell 16 percent on the NASDAQ. American investors rushed to Moscow to talk to Yandex’s management, which responded by saying that international investors’ participation was normal for a tech startup and that, as a public company with a 70 percent free float, no single shareholder could exert pressure. Yandex reminded all who asked that Russia was one of the few countries where domestic Internet brands were stronger than global ones. In early May 2014, a worried Yandex recruited to its board German Gref, CEO of the huge state-owned Sberbank and who is thought to be personally close to Putin. It soon became apparent that Putin had not casually raised questions about Yandex.

That same month, Andrei Lugovoi, the Member of Parliament who in March sponsored legislation making it possible to block inside Russia Ej.ru, Grani.ru, Kasparov.ru, and Navalny’s blog, announced a new initiative to force Yandex to register as a media company. It was an unmistakable threat. In a week, the Russian Investigative Committee, an increasingly powerful law enforcement body, sent representatives to Yandex offices with a search warrant. The pretext for the warrant was a criminal investigation against Navalny, alleging he had stolen money he gathered using Yandex, and which had been intended for his campaign for Moscow mayor the previous fall. But the raid was a shocking development. Yandex was one of the most famous Russian companies and inspired pride in Russia. Its profitability came not from oil and gas, traditional sources of Russian wealth, but through building a business based on technology, and here, in this field, Russian engineers competed successfully with American companies. Yandex had a bigger share of the Russian search market than Google did.

UNEASE ALONG THE YAUZA

Many in the Internet industry were becoming uneasy that Putin was no longer hesitating to attack the pride of Russian business. Russian high-tech companies often had foreigners on their boards. They were a ticket to world markets and foreign investments. For years, it was a sign of success. Now Putin turned the tables and made a foreigner on the board look suspicious, effectively an agent of a foreign state. The business community searched frantically for an explanation—a way to understand the new Kremlin policy toward the Internet. It took a month for Putin to deliver his explanation.

On June 10, 2014, Putin scheduled a meeting with the leaders of the Russian Internet. The venue chosen for the meeting was the forum of Internet entrepreneurship in the Silver City business center, on the embankment of Moscow’s Yauza River. The leaders of the Internet industry received personal invitations from the Kremlin to attend. In the run-up to the meeting, many observers recalled the conversation that then-Prime Minister Putin held with Internet professionals on Dec. 28, 1999—the first and only in that format in the past 15 years. In December 1999, Putin wanted to look very much like a liberal leader and pledged not to sign any legislation concerning the Internet without a full public debate—which of course has never taken place.

Still, over the course of those 15 years, the Russian Internet has evolved into an industry doing more than 5 trillion rubles ($143 billion) in business annually, employing 1.3 million IT professionals, generating 8.5 percent of Russia’s gross domestic product, and accounting for 2.5 percent of all its trade. And this in a nation whose economy is dominated by oil and gas. Almost every market is now connected in some way with the Internet. What’s more, Russian companies have shown they are able to dominate the domestic Internet market even after global corporations entered the fray.

But the people invited to the meeting with Putin did not behave like the leaders of such a powerful industry. Many had hoped the meeting would provide a forum to discuss the disastrous impact of two years of state regulations on the Russian Internet. They also hoped industry leaders would present a united front against the President.

Instead, the subject of regulation was barely raised. Only Dmitry Grishin of Mail.Ru, the biggest email service of the country, found the courage to raise the question of Internet regulation. He began by saying that most Russian software advances had happened because the state left the inventors alone. Then Grishin said, “We have this mentality that we count on ourselves.” He added that any contacts with authorities can’t lead to good things, and “in principle, if you can hide, it is better to hide.”

Putin sternly interrupted him. “It’s wrong,” he said, shaking his head, and then snapped, “First of all, you can’t hide from us.” The remark said everything about the state of the Internet in Russia. It had grown immensely, had enabled appeals for freedom, and yet there was no place to hide.

Grishin reddened and replied nervously, “We often hear that all Internet users are from another planet. But we do love our country; we want to help to make it comfortable to live and work in. And we understand that the Internet has grown, and it is now an integral part of the society. Therefore, in principle, we understand that the regulation, is necessary. And often the ideas in the regulation, they are very correct. But, unfortunately, sometimes it happens that realization, in general, is frightening. And it would be great to develop some sort of process that allows us not only to listen but also to be listened to. It would be very, very important!”

Russia’s Internet industry leaders had failed to present their collective case to Putin. The only real beneficiary of this meeting appears to have been the All-Russia People’s Front. The meeting was organized by the Internet Initiatives Development Fund, established in March 2013 by the Agency for Strategic Initiatives—itself created by the Russian government. That foundation is headed by a former engineer for Uralmash, the heavy machinery manufacturer, who was a Putin ally in the 2012 elections, and All-Russia People’s Front leader Kirill Varlamov. Sitting beside Putin during the meeting, Varlamov fully exploited the opportunity to present his fund’s startups to those present, including Arkady Volozh of Yandex, Grishin of Mail.Ru group, German Klimenko of LiveInternet.ru, and Maelle Gavet of Ozon. Beyond politely refusing to ask hard questions of Putin, these genuine market leaders lent legitimacy to one of Putin’s government-funded pet projects.

The Russian Internet companies were also hastening to prove their loyalty to the Kremlin’s stand in Ukraine. By then, Yandex already offered different maps of Ukraine for Russian and Ukrainian users. Russians would see a map showing Crimea as part of Russia, while a user in Ukraine would see the peninsula as still part of Ukraine. Mission accomplished, now the Kremlin could focus on its next, far bigger goal, with substantially larger stakes—chasing after the global platforms of Google, Facebook, and Twitter.

TIGHTENING THE SCREWS

A month before his meeting with Russia’s Internet leaders, Putin signed a new law aimed at tightening the controls over the many popular online bloggers in Russia who carried out lively and relatively free debates on the Internet. It became known as the “Bloggers Law,” and required bloggers with more than 3,000 followers to register with the government.

Registration was more than a mere formality. It would give security services a way to track them, intimidate them, or close them down. Once registered like the news media, a blogger would be subject to state regulation. But beyond simply registration, the law mandated that bloggers not remain anonymous and that social media would maintain computer records on Russian soil of everything posted over the previous six months.

The law marked a first legislative step to force global social media to relocate their servers to Russia. At their headquarters in California, both Twitter and Facebook said they were studying the law but would not comment further.

The second step was taken two months later. On July 4, 2014, the State Duma passed another law prohibiting the storage of Russians’ personal data anywhere but in Russia. Members of Parliament pointed to Snowden’s revelations of mass surveillance to justify the action. In fact, nobody asked Duma deputies to protect their personal data. In contrast to the people of Brazil, whose outrage over U.S. National Security Agency spying led to a similar draft law, Russians were not especially shocked by recent revelations about Washington’s global cyber espionage. On the contrary, Russian civic organizations strongly opposed the law.

The law stipulated that global platforms would relocate their servers to Russia by Sept. 1, 2015. The meaning of the move was clear—to increase government control and surveillance of the Internet. As reported in World Policy Journal in the fall of 2013, Russian security agencies enjoy unrestricted access to Internet traffic that passes through Russia and large stretches of the former Soviet Union. As part of the long-running System for Operational Investigative Activities, known by its Russian acronym SORM, surveillance equipment has been installed by all Russian Internet service providers and mobile and landline network operators, allowing several government agencies to directly monitor communications. To ensure a nationwide system of surveillance, the Russian legislation requires all Internet-service providers, from cable operators to companies which provide hosting for servers, to have a backdoor accessible to security services.

As soon as the global services began operating on Russian territory, they became subject to Russian jurisdiction, and thus required to provide access to their servers.

In 2014 and 2015, all three global platforms—Google, Twitter, and Facebook—sent high-ranking representatives to Moscow. Details of their talks were kept secret. However, in March 2015, the Ministry of Communications convened a gathering of the biggest Russian data centers to discuss the relocation of servers. A representative of Rostelecom, a state-controlled Russian communications company, stepped in to announce that Google had already relocated its servers to the operator’s data center, adding, “The Company [Google] is our client now, and we are a restricted access, semi-government facility.” Google, as well as Facebook and Twitter, failed to respond to repeated requests for comment by World Policy Journal.

On July 16, 2015, Roskomnadzor announced at the meeting with IT business leaders that the agency intends to check 317 companies from September to December 2015 to verify their compliance with the new legislation. Roskomnadzor officials made clear that Google and Facebook are not on the list of 317 companies to be inspected, thereby giving the global platforms another four months to relocate their servers to Russian soil. The most intriguing comment was made about Twitter. Russian officials said Twitter is not subject to this law, for reasons that have still not been disclosed. It doesn’t mean Twitter has escaped the trap, though. The company should have its servers located in Russia under provisions of another piece of legislation—the Bloggers Law.

COERCION

Putin is accustomed to dealing with individuals and organizations that could be coerced if their management is threatened by the state. This strategy was used to control traditional media in the early 2000s. NTV, then the most popular TV channel in Russia, and critical of the Second Chechen War and Putin personally, was brought to heel thanks to direct attacks on its management and owners, including the brief detention of Vladimir Gusinsky, the oligarch who had launched NTV. Eventually, Gusinsky was forced to leave the country, and the same approach is being used against the Internet. But networks have no traditional hierarchy. They are horizontal creatures. Everyone can participate without authorization. The content is generated not by the companies that operate websites and social media but by the users.

This miscalculation quickly became evident during the conflict in Ukraine. The most closely guarded secret for the Kremlin is the presence of Russian soldiers on Ukrainian soil.

The Kremlin and the Ministry of Defense have been flatly denying accusations of Russian boots on the ground—claiming that neither military equipment nor soldiers were sent to Ukraine to help Russian-backed separatists. Putin himself famously suggested that Russian uniforms could be easily bought in a store.

Yet, throughout 2014 and into 2015, Russian and Ukrainian journalists and activists found dozens of profiles of Russian soldiers on Vkontakte, boasting of their exploits in Ukraine. Eventually, wives of soldiers killed in action began posting soldiers’ accounts and inviting friends to attend their funerals.

By then, Vkontakte as a company was under the firm control of the oligarchs loyal to the Kremlin—its founder long gone from Russia. But soldiers and their widows didn’t care about the change of management in Vkontakte. They simply posted their photographs and their comments. The primary source of sensitive data on the Russian role in Ukraine was not journalists, NGOs, activists, or even bloggers. It was soldiers—users of vk.com, a broad but by no means easily controlled segment of the Russian people.

Regardless of the challenges involved in controlling a website, let alone the Internet at large, the goal of the Kremlin remains clear—to make all Internet services, either Russian or international, available on Russian soil and within the reach of the government. The government’s view is that websites must be open to surveillance, or direct intrusion. Such control would extend to the ability to shut down the service in case of an emergency—as defined by the Kremlin. The central question is how to respond to this type of pressure—by technical means or political. So far, the Russian approach is based on intimidation rather than technology. Internet filtering in the country is porous and not very sophisticated—hardly approaching the ability of Soviet-era efforts to jam all Russian-language radio transmissions of foreign broadcasters, including Radio Liberty, Voice of America, and the BBC.

Today, it’s entirely possibly for a reasonably adept individual in Russia to reach a banned site using TOR (The Onion Router, free software enabling anonymous Internet access), or even the Google Translate service. It is the cooperation of Internet companies with the Kremlin that assures the government the control it still maintains and seeks to expand.

The history of the Cold War shows that the Soviet Union always lost in one area—technology. It barely fulfilled many basic needs in terms of consumer goods, communications, food, clothing, and housing. And even in military production, where the Soviet Union excelled, it also fell short.

But the Internet represents a challenge beyond any of these efforts. It thrives on a type of technology that’s in sharp contrast to the systems the Kremlin is accustomed to controlling. It’s horizontal, lacks hierarchy, and is fast-developing. This is its strength, and where the Kremlin, despite all its efforts, may fail.

*****

*****

Andrei Soldatov and Irina Borogan, specialists on Russian security, are the authors of The Red Web: The Struggle Between Russian Digital Dictators and the New Online Revolutionaries, published by Public Affairs in September. Founders of Agentura.ru, they last published The New Nobility.