This is the first in a series of articles covering Turkish politics leading up to the general elections on Nov. 1. It aims to provide background information on the four major political parties in Turkey and examine recent developments in their relationships with one another.

By Laurel Jarombek

Turkish politics are in a state of flux. Parliamentary elections in June failed to yield a majority for the ruling party, and negotiations to form a coalition government fell through. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan then called for a new round of elections, which have been scheduled for Nov. 1. In the meantime, the country’s more moderate parties have moved further away from the political center, and the main parties’ attacks on one another in the press are becoming increasingly vitriolic.

There are four main political parties in Turkey, all of which managed to draw more than 10 percent of the popular vote in June, allowing them to claim seats in the Grand National Assembly. The Justice and Development Party (AKP), led by Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu, has the largest base of the four. Its religious, conservative platform resonates with many in Turkey, and until June, the party’s support had been rising steadily among voters since it emerged on the political scene in 2002.

June 7 election results, depicting districts won by AKP (yellow), CHP (red), MHP (dark red), and HDP (purple)

The Republican People’s Party (CHP) is Turkey’s second party, winning a quarter of the vote in June. Led by Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, the CHP is the largest secular, progressive, and European-oriented opposition party. The third and fourth place parties, the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) and the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), respectively, represent political movements that have attracted less mainstream support than the AKP or CHP.

The MHP is a right-leaning, ultra-nationalist party, representing a more extreme current of Turkish ethnic nationalism. The HDP, on the other hand, advocates for democratic socialism and minority rights. The party draws most of its support from the Kurdish population, but its pro-LGBT and pro-gender equality platform also attracts liberal voters in western Turkey. It is co-chaired by a man and a woman, Selahattin Demirtaş and Figen Yüksekdağ. In the June elections, the MHP was ahead of the HDP by only a few percentage points, so the third place position in November is considered up for grabs.

The four parties and their leaders, from most conservative (MHP) to most liberal (HDP)

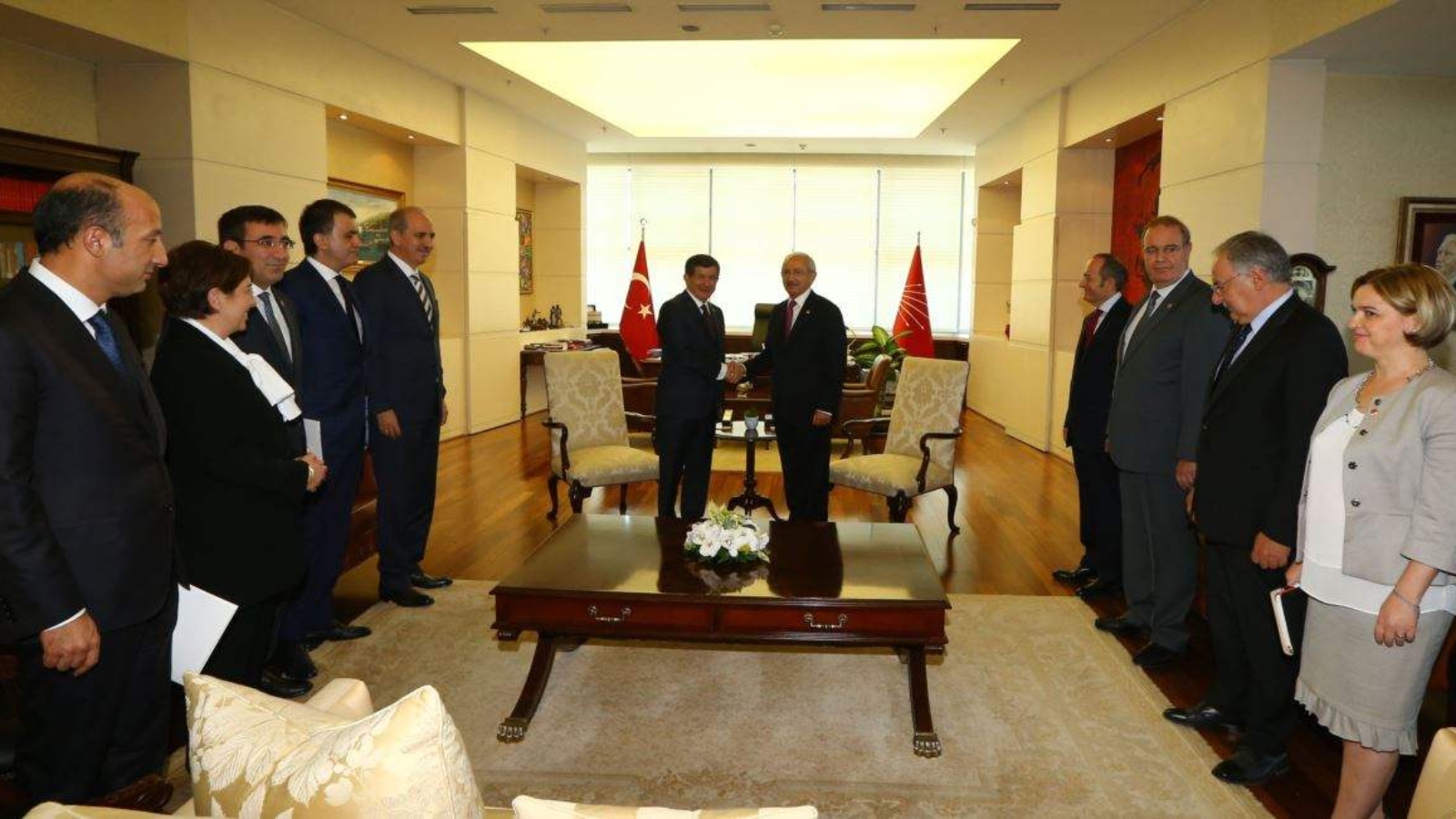

Now that building a coalition is necessary to forming a viable government for the first time in its 13-year rule, the AKP is having trouble reaching agreements with the other major political parties, largely due to President Erdoğan’s intransigence. Although Erdoğan is no longer officially affiliated with the AKP, he remains the party’s de facto leader. According to Yurter Özcan, CHP Representative to the United States, the CHP leadership “had the impression that Davutoğlu was more in favor of a coalition and was more constructive during the talks,” while Erdoğan was strongly opposed to joining forces with the CHP. The negotiations fell through as a result.

Hakan Yılmaz, Professor of Political Science and International Relations at Boğaziçi University, argues that although an AKP-CHP alliance would have been a sensible and stabilizing development, worries about an opposition party reopening charges regarding the December 2013 corruption scandal made such a partnership less attractive to the AKP. Ultimately, Yılmaz said, “Erdoğan couldn’t risk sharing government with the CHP.”

Erdoğan has become such a divisive figure that, as Professor Yeşim Arat of Boğaziçi University contends, “The main cleavage of the moment in Turkey is between the [P]resident and those who oppose his one man rule.” Since the AKP is inextricably linked to Erdoğan and his quest for greater personal power, hostility toward the party is strong among opposition groups that might otherwise find common ground with parts of the AKP’s policy agenda.

The AKP has alienated many voters and opposition politicians by refusing to revitalize the peace process with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), the Kurdish militant group that has been fighting with Turkish military and police forces for the past few months. In its first few terms in office, the AKP had significant support from Turkey’s Kurdish population; nearly all Kurds in the southeastern part of the country who did not vote for a Kurdish or Kurdish rights-focused party voted for the AKP. Now, however, support for the HDP among Kurds is 70 percent and rising. The probability of an AKP-HDP alliance was never high – the ideological distance between the parties is too great – but any remaining perception of the AKP as a supporter of Kurdish rights is gone.

Meanwhile, the HDP has been denouncing Erdoğan and the AKP for allowing the country to descend into violence. After the AKP’s coalition talks stalled in June, the HDP was the only party that agreed to join the interim cabinet that would govern the country until the new elections in November. On Sept. 22, however, the two HDP ministers, Ali Haydar Konca and Müslüm Doğan, resigned their posts. In a press conference shortly after his resignation, Konca alleged that Erdoğan and the AKP had “facilitated a war and coup mentality against the June 7 election results starting June 8.” This interpretation of events is not new, but the HDP’s change in official policy signals even further estrangement from the AKP.

Results of the June 7 elections

The AKP has been fortifying its nationalist credentials by engaging in conflict with the PKK. Turkish nationalism has historically characterized the Republic of Turkey as an ethnically Turkish state, largely ignoring the roughly 25 to 30 percent of the population comprised of Kurds and other minority groups. The AKP has recently been moving away from its previously pro-Kurdish position, and according to Yılmaz, the new direction of AKP policy is more or less in line with the MHP’s ultra-nationalism.

While the AKP has been moving closer to the MHP on the ideological scale, there are indications of convergence between the CHP and the HDP. The CHP and the HDP are still quite distinct from one another; the HDP is more left-leaning than the CHP, and while the HDP’s base lies squarely in Turkey’s Kurdish-majority provinces, the CHP draws hardly any votes from that region. But speaking on behalf of the CHP, Özcan contends, “We have become more progressive in how we approach the Kurdish problem.” The CHP has begun to push for an official investigation of the violence in southeastern Turkey, which the HDP has been advocating for months.

HDP co-chair Selahattin Demirtaş also made a statement recently citing his party’s and the CHP’s shared values of “peace, freedom, and democracy” and expressing openness to future cooperation. The common ground in the CHP’s and the HDP’s policies may allow the two parties to put their combined weight behind a liberal reform effort, but it also puts them both more at odds than ever with the AKP’s increasingly nationalist and authoritarian tendencies.

As the AKP pulls further away from the political center, the gap between the policies of the ruling party and those of its more liberal opponents grows wider. The policies of the left and right have grown more polarized, with the CHP and HDP on one side and the AKP and MHP on the other. Not all of the disagreement is ideological, though. All three opposition parties – the CHP, HDP, and MHP – strongly condemn President Erdoğan’s effort to consolidate power, and resist cooperating with the AKP because of Erdoğan’s personal ambitions. The exacerbation of the divides between right and left, and between Erdoğan and the rest, is creating a poisonous political environment in the run-up to Turkey’s November elections.

*****

*****

Laurel Jarombek is an editorial assistant at World Policy Journal.

[Photo and map image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons]