|

WORLD POLICY JOURNAL

“Let Me Hear My Brother!” [Go to interactive discussion forum]

It’s what was missing that haunted this American while visiting the Aegean coast of Turkey, the fecund cradle from which so much of the modern world emerged. Here, four thousand years ago, in thriving commercial seaports, ethnic Greeks began using currency, devised an alphabet, drew maps, composed Europe’s earliest epics and genuine histories, and examined skeptically the cosmos above and the earth below. In an underrated epilogue, Asia Minor later served for half a millennium as a laboratory of multicultural civility. As confirmed bountifully in Roman era inscriptions, the inhabitants of Asia Minor’s hellenized cities knew well the excellence of their temples, theaters, libraries, council chambers, fire departments, gardens, aqueducts, hospitals, baths, and arcaded markets—the vital and enlivening ingredients of urban life. Little wonder so many travelers have been drawn to the eloquent remains of Ephesus, Miletus, Pergamon, and Aphrodisias, to mention only the most celebrated of half a hundred sites. Eloquent, but mute. There is no living echo from the Greeks who until the 1920s inhabited Aegean Turkey. They left en masse in a half-forgotten tragedy arising from an ill-starred campaign by mainland Hellenes, rashly encouraged by Prime Minister David Lloyd George, to retake Asia Minor. The Turks, led by Mustafa Kemal, drove back Greek invaders in a brutal war whose atrocities shamed both sides.

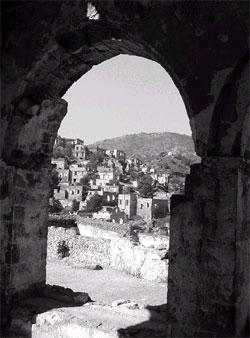

Out of the mire emerged the Turkish Republic, its frontiers delineated in the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, which also provided for a population exchange—more than a million ethnic Greeks and nearly 400,000 ethnic Turks resettled reciprocally, a massive uprooting that sowed enduring enmities. Given the bitter circumstances, there may have been no alternative to this drastic surgery. Yet a melancholy silence seems still to surround the exchange, so that it is something of a shock to find an unusual and anomalous reminder near the seaport of Marmaris, favored by British tourists. On a hillside overlooking the lovely Turquoise Coast, day-trippers wander through the modern ruin of Kayaköy, a hillside ghost town consisting of 400 roofless houses and the stark remains of a large Orthodox church. As a marker explains, with strenuous understatement, “Shortly after the proclamation of the Turkish Republic, the Greeks living in the region were exchanged with Turks living in western Thrace, which resulted in the houses being vacated.” One can deduce the unmentioned furies set loose at the time in the wholesale vandalism that turned these concrete homes into gaping shells. (It needs adding that the ruins are now protected and preserved by a foundation dedicated to Greek-Turkish reconciliation.). The silence has also been broken in a poem, “Memory II,” by George Seferis, winner of a Nobel Prize in letters. Born in Asia Minor’s once most populous Hellenic center, Smyrna (now Izmir), he was a teenager when his family left Turkey in 1914 to settle in Europe. On returning in 1950 to his birthplace, he wandered with a companion among classical ruins along the coast. As translated by Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard, the poem concludes: “I remember still: / he was traveling to Ionian shores, / to empty shells of theaters / where only the lizard slithers over dry stones, / and I asked him: ‘Will they be full again some day?’ / and he answered: ‘Maybe, at the hour of death.’ / And he ran across the orchestra howling / ‘Let me hear my brother!’” This cry of anguish needs recalling at a moment when frustrated Americans, sometimes soberly and thoughtfully, sometimes too casually, propose cutting fractious Iraq into three countries, with homelands for Kurds, Shiites, and Sunnis. The legacy of forcible migrations arising from past partitions does not encourage optimism. The uprooted become exiles, those remaining behind commonly suffer degraded citizenship, as in the case of India-Pakistan, Israel-Palestine, the two Irelands, and divided Cyprus. With the welcome capture of Saddam Hussein, it may now be more likely to encourage formation of a federal government providing a common citizenship and minority rights for all Iraqis. And, in the happy event of Turkey’s admission to the European Union, a more universal citizenship would make it possible for uprooted Greeks and Turks, or their offspring, to reestablish themselves in their respective former homelands. On Staying Away in Droves Why the absence? For years, American tourists have flocked to Turkey, with its friendly people, its fine hotels, excellent cuisine, and richly layered legacy of classical antiquity, Byzantium, and the Ottoman Empire. The war in Iraq has not deterred visitors from Britain, Germany, France, Scandinavia, or Italy—they were visible everywhere. Why the contrast? An obvious explanation for Americans’ absence is a wary fear of being targeted in a Muslim country. A less charitable view is that Americans are unwilling to incur even the most minimal risks in visiting countries like Turkey out of excessive and unseemly caution. It would be heartening if President George W. Bush appealed to young, adventurous, and able-bodied Americans to defy the zealots, and whenever possible to vote with their air tickets by visiting allies like Turkey. For Turkey, the collapse of American tourism has been but one more penalty incurred by two Gulf wars. In Izmir, we rented a compact, Turkish-assembled Fiat, of which three could be squeezed into the average American SUV. It cost the equivalent of $80 to fill the tank. Inflated petrol prices, which bear heavily on taxis, trucks, buses, and tractors, have been among the obvious costs for Turkey of trade sanctions imposed on Iraq for more than a decade. Small wonder that the traveler encounters so few vehicles on the fine and costly Turkish highways along the Aegean, improved recently to impress the European Union, and now yet one more sign of a floundering economy. And with the November terror attacks in Istanbul, Turkey faces an even leaner year. Is it beyond human wit for someone in Washington to ensure that Turkey will be at the head of the queue when Iraq once again can legally export cheaper oil? The Stature of Atatürk The vast site is meticulously tended by the war graves commissions of the respective national combatants, its extensive trenches and hecatombs clearly marked, amidst vistas of incomparable and poignant serenity. But for many of us, its most healing memorial were these words, inscribed on a tablet and spoken in 1934 at the dedication of a cemetery by the battle’s Turkish hero and founder of the Turkish Republic: “Those [Allied] heroes that shed their blood and lost their lives…you are now in the soil of a friendly country. Therefore rest in peace. There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets to us when they lie side by side. You, the mothers who lost their sons from far away countries, wipe away your tears; your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace. After having lost their lives on this land, they have become our sons as well.” What sets Atatürk apart from the contemporary procession of nation-founders who with honorable exceptions have crowned themselves liberators-for-life, was the magnanimity evident in those words, together with his willingness to risk his political capital on difficult, radical, and contentious steps, ranging from enfranchising women to changing the Turkish alphabet. He was inarguably fallible, but how much taller Atatürk stands than leaders like the late president of Azerbaijan, Heidar Aliev. With autocratic powers, Aliev squandered his political capital on securing the succession of his son, to whom he bequeathed Azerbaijan’s long and self-injuring conflict with Armenia over contested Nagorno-Karabakh. For years, mediators hoped that Aliev would persuade his people to accept difficult truths about a lost war. He never did, leaving as many as a million displaced persons as his memorial. —Karl E. Meyer [Go to interactive discussion forum]

|