As the global gap between the haves and the have-not grows ever wider, attention focuses on the top and the bottom of the socioeconomic spectrum. But what about the middle? Creating sustainable development might ultimately hinge on how we understand “middle class,” since achieving that vaguely defined status is now the ambition of billions of people. To find out what it means to be middle class, World Policy Journal chose to explore three countries at different levels of economic development—Liberia, with a per capita annual income of roughly $400; Indonesia, at around $4,000; and the Netherlands, at around $40,000. We asked writers in each country to profile its middle class—its aspirations, politics, and prospects.

*****

*****

THE NETHERLANDS: PROSPERITY AND POPULISM

By Bas Heijne

AMSTERDAM—For the Dutch middle class, it appears, it is the best of times and the worst of times. Dutch men and women are almost completely happy about their lives, surveys suggest, with their satisfaction levels reaching an almost unimaginable 80 percent. When they open the front doors of their tidy houses and look outside, however, it’s another story altogether. Beyond their lives and families, they see a society that has gone wrong in all sorts of ways. The Dutch, it seems, are happy with their private lives, but decidedly unhappy with public life. Pollsters hear the same social ills cited repeatedly—unfriendliness and downright rudeness in public space, other parents raising unruly children, stifling bureaucracy, and a general lack of public spirit.

During the past decade or so, this form of discontent has created a surprisingly receptive audience among the Dutch middle class for a new breed of populist politicians who define the state of Dutch of society in apocalyptic terms. The first politician to recognize the opportunity this presented was a maverick named Pim Fortuyn, who built a devoted following by peddling a vision of a country in ruins, a nation whose identity was being wiped out by immigrants—especially Muslims—who refused to assimilate culturally. Without hesitation, Fortuyn compared himself to Moses, leading his people back to the Promised Land. In May 2002, just before national elections, his party was leading in the polls. Fortuyn was already choosing a suit for his inauguration as Prime Minister when he was shot to death in a parking lot outside a television studio, murdered by a radical environmentalist. In the aftermath of his shocking assassination, many of his followers called him a messiah, a redeemer.

Fortuyn’s natural successor is Geert Wilders, the leader of the Freedom Party. In spite of his flamboyantly bleached hair, Wilders is a much less exuberant figure. He is, however, far more radical in his views. So far, his movement has captured only about 15 percent of the vote. Yet his view of the state of Dutch society is widely shared, even by many of his political opponents. Wilders’ main concern is the so-called “Islamization” of Dutch society—a largely imaginary smothering of liberal Dutch values by an aggressive and oppressive Islam. Wilders’ activities consist mostly of an ongoing campaign of verbal attacks on Dutch Muslims, and many of his policy ideas are no more than cheap provocations, including a proposed tax on the Muslim headscarf, which he calls a kopvoddentax—a “head-rag tax.” (It sounds even worse in Dutch.)

While some of these antics are frowned upon even within Wilders’ own constituency, the basic tenets of his revolt have become completely mainstream. Crime rates continue to fall, and there has been no sharp decline in income, even during the global recession. Yet, all evidence to the contrary, conventional wisdom now holds that the Dutch middle class is in crisis. In a feat requiring no small amount of political talent, the populist right has fueled a form of social and political schizophrenia, fostering a support base of middle-class voters who are prosperous and content—but terrified and furious at the same time.

EGALITARIAN FANTASIES

The Dutch generally do not like to talk about class, and their collective prosperity has usually allowed them to avoid the topic. Per capita annual income is around $40,000, ten times the level that the World Bank considers “middle income” by global standards. The Low Countries have a long tradition of egalitarianism, and during the revolutionary 1960s, progressive ideas about equality became mainstream, as the country moved away from strict, stultifying divisions between various Christian denominations. These days, more or less everybody is supposed to be middle class in this nation of more than 16 million.

This is a fantasy. Though income disparity is modest compared to many other developed Western societies, there are quite a few fabulously wealthy Dutch citizens, while about 10 percent of the population lives below the official poverty line. Still, the image of an all-inclusive middle class endures. Very few Dutch citizens identify as “working class,” and on the other end of the spectrum, a great effort is made to avoid seeming too wealthy.

High-end retailers, like the Albert Heijn chain of supermarkets, cater to the expensive tastes of Dutch families with plenty of disposable income, but market a very specific kind of luxury—one that is accessible to all. Faced with public anger over a financial scandal at its parent company and the extremely generous compensation package that was promised to its CEO, Albert Heijn responded with an ad campaign meant to convey an ethos of modesty and averageness. The supermarket’s advertisements now feature a shop manager played by an actor who radiates “average Dutchman”—a balding, decidedly unglamorous figure. Even the royal family is supposed to behave as if it were middle class. On Queensday, the national holiday that celebrates the country’s monarchy, the royals visit small towns around the country and take part in traditional local festivities. They travel just the way their subjects might—by bus.

THE NEW POPULISTS

Wilders’ far-right movement has attracted voters who are beginning to doubt whether they are part of this supposedly expansive middle class. Many live in poorer neighborhoods in the bigger cities and feel left behind by economic growth and globalization. The genius of the new populists like Fortuyn and Wilders has been to tap into this anxiety without also engaging in economic populism—indeed, by ignoring economic issues almost entirely. What they are really exploiting is the fear of loss of identity—national, local, even existential. They have built a political movement around an anti-immigrant sentiment expressed in almost purely cultural terms, allowing them to attack and scapegoat the less affluent—the immigrant lower classes—without referring to class. In their vision, the problem with Muslim immigrants isn’t only that they commit crimes, or that they are a drain on the social-welfare system, or that they are dragging down standards of living. Instead, the real problem is Islam. The problem with poor immigrants isn’t the fact that they’re relatively poor, or that they are not middle-class enough—the problem is that they’re not “Dutch” enough.

The puzzled reaction of the political establishment to the fact that this message appeals to sizable sections of the Dutch electorate reveals a form of honest ignorance. The preoccupations of the populist right simply do not make sense to most mainstream leaders, and they have struggled in vain to find an effective response. This traditional political establishment now stands accused of betraying its own social-democratic principles. Its representatives still speak the language of equality and social commitment, but they are no longer perceived as caring for the common good. In the new populist mindset, the establishment is identified as the enemy within—committed to a vapid multiculturalism, forever stuck in 1968, when, in the view of Wilders and his followers, the old ideals of social democracy were betrayed by a group of romantic egotists lusting for power.

The irony, of course, is that the rise of right-wing populism is a powerful tribute to the real and unquestioned prosperity and economic stability of the Dutch middle class. After all, only a relatively prosperous electorate could afford to become obsessed with the “Islamization” of the Netherlands and the bureaucratic wastefulness of the European Union.

COMPETING NOSTALGIAS

What remains to be seen is whether this populist moment will truly bring a close to the decades-long Dutch experiment in progressive politics. The 1960s marked the end of the system of so-called “pillarization,” as many Dutch broke loose from a narrow sense of group identity derived from various denominations of Christianity (and for that matter, socialism)—the traditional sources of security and comfort. Dutch political culture became increasingly focused on personal freedom and the rejection of dogma and tradition. European unity, multiculturalism, and secularism became the new consensus values; personal emancipation, economic prosperity and security the new consensus political ideals. The Dutch developed a reputation for an almost radical form of tolerance—a relaxed attitude toward soft drugs, homosexuality, abortion and, later, euthanasia. To the surprise of many outside the Netherlands, these issues were resolved without much protest or even debate.

For those who applauded Dutch pragmatism and tolerance, the sudden rise of right-wing populism came as a big surprise. It should not have. With the total embrace of personal freedom and self-expression, the idea of what makes a coherent society was lost somewhere. Common social unifiers lost their appeal. Nationalism became deeply suspect. Other ideas of community—including class solidarity—were largely discarded as old-fashioned, folkloric or simply stupid. Identity could only be discussed as a personal matter. This development undeniably aided in the further emancipation of women, gays, blacks and immigrants. But it also undermined any attempts to foster social cohesion—creating a vacuum that right-wing populists like Fortuyn and Wilders and found quite easy to fill.

So far, the progressive-minded establishment has largely failed to counter the seemingly inexorable rise of populism. In the meantime, perhaps the most potent competition to the right-wing vision is coming not from within the political realm, but from the world of popular culture. There, a form of middle-class consciousness seems to be emerging, fueled by a vaguely nationalistic nostalgia for a less fragmented society—a nostalgia that is more sentimental than angry. Many television commercials now stress the “typically Dutch” qualities of products. A Dutch offshoot of the British cellular provider Vodafone promises a simple and honest “Dutch way” of dealing with customers. A new game show called I Love Holland attracts millions of viewers every week, even though it offers few (if any) prizes and no dramatic competitions. Contestants are quizzed about language, Dutch historical figures, and present-day media celebrities—all designed to promote a feeling of shared togetherness.

The most successful of these efforts is a “reality” show called Farmer Seeks Wife, which chronicles the romantic adventures of Dutch farmers searching for partners to share the burden of milking cows and harvesting crops. In its fifth season, the show broke viewership records. One episode garnered more than five million viewers, surpassing the audiences for news reports about natural disasters or royal weddings. In one way, it is a typical dating show. The farmers, mostly young men, appear as the Dutch equivalent of the Noble Savage—socially awkward and naïve about women and affairs of the heart. The women who participate come from the other end of Dutch society. They are worldly, tired of the dating game and looking for a much simpler life. These would be recognizable types in any modern society. But the real explanation of the show’s success is the vision of Dutch society it promotes—a Holland that is simple and humane, unthreatened by the dark forces of globalization and immigration. The innocence that radiates from the program may be cleverly manipulated by its makers, but its appeal serves as proof that the so-called crisis of the Dutch middle class has more to do with a desire for a shared identity than with economic inequality. The shows might be silly, and the entertainment executives behind them are hardly creative geniuses. But when it comes to understanding the Dutch public, they are light-years ahead of the country’s political establishment.

*****

*****

Bas Heijne, a Dutch novelist and essayist, is a columnist for NRC Handelsblad, a daily newspaper based in Rotterdam.

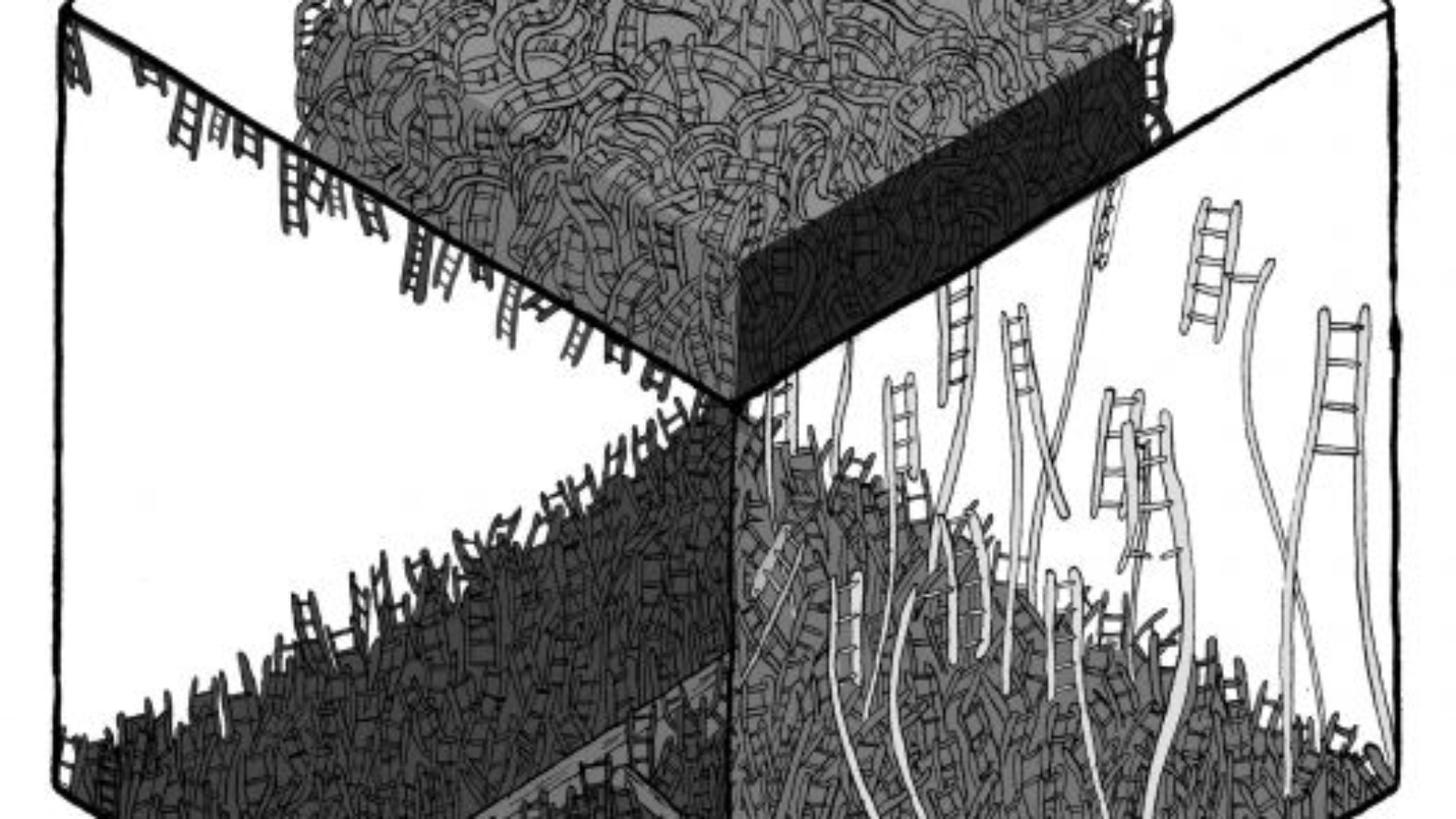

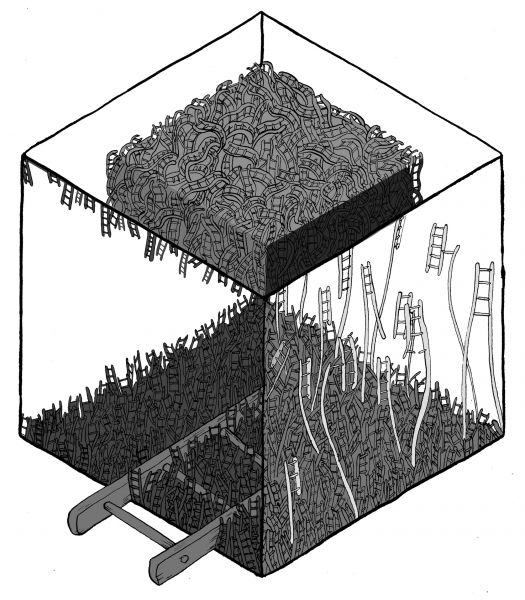

[Illustration: Marshall Hopkins]