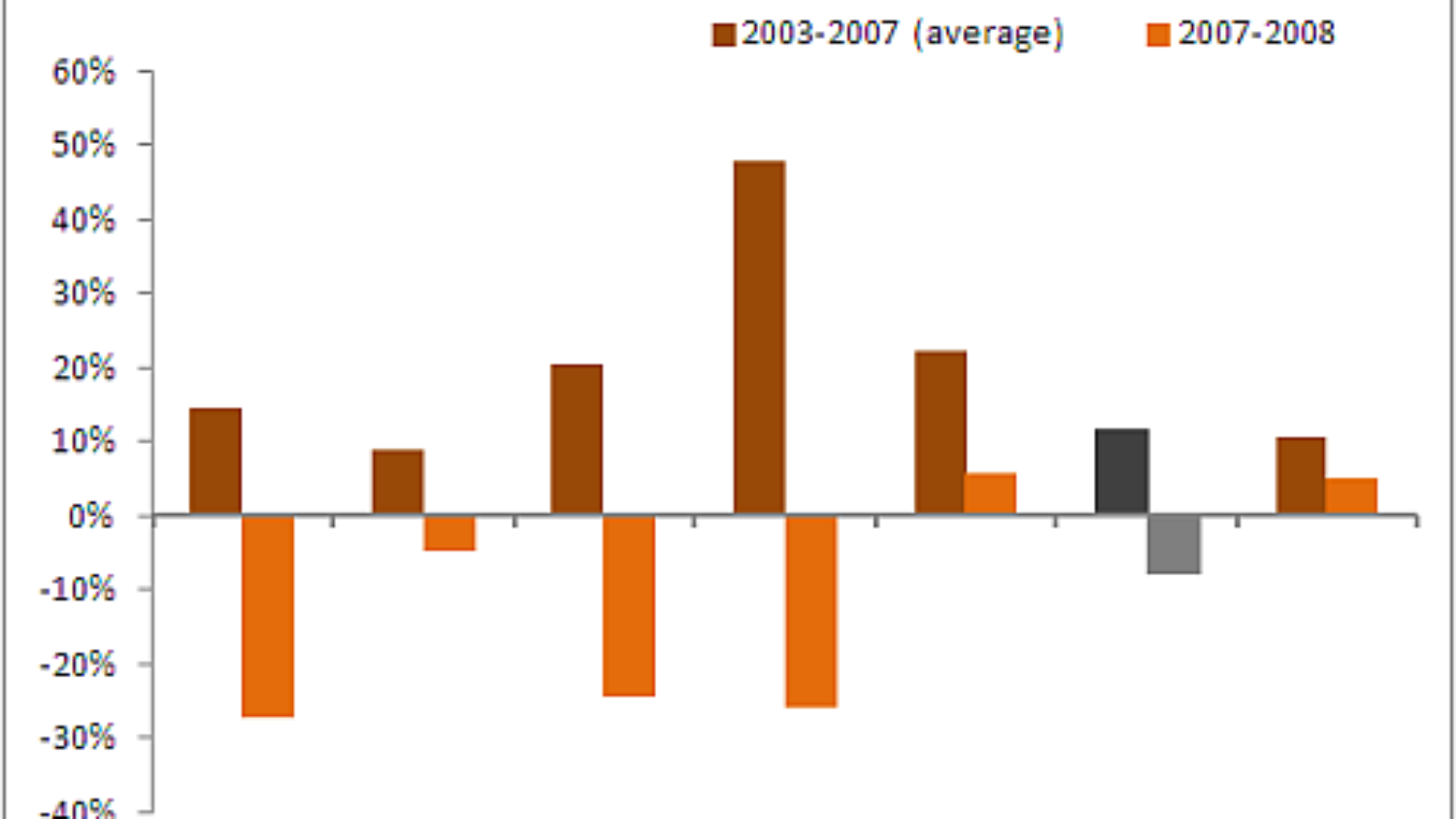

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) released a report Monday indicating a sharp drop in immigration to some of its 23 member countries at the onset of the global recession. The Paris-based think tank estimated that the annual rate of immigration to the group dropped 6%, to 4.4 million in 2008, after five years of average increases of 11%. Europe–particularly countries such as Spain, Italy, Ireland–accounted for most of the slowdown, with rates not affected much in North America, Oceania, Korea or Japan.

In his speech addressing the report, Angel Gurría, OECD Secretary-General, urged that, “mainstream active labor market measures must be structured so that immigrants have the same access as the native-born. That makes economic sense, as labor markets will eventually recover and long-term needs for skills will reassert themselves.”Specific judgments cannot be made about the data from country to country–each government uses different measures of immigration (from population registers to residence permits to records of employment) and procedures for data collection with varying degrees of accuracy, there is likely to be large variability in the numbers. But it’s easy to pick out some broader trends.

Unemployment among immigrants is higher, as employers are more reluctant to hire and more likely to fire. Immigration policies have also become more restrictive, with “employment tests being applied more strictly,” according to Gurría. But the immigration slowdown occurred most strikingly in the semi-periphery of Europe, in countries with immigration policies that were, until the recession, quite generous and had attracted record numbers.

The OECD countries with the most severe drops can be broken down into three groups, composed of countries that share similar economic profiles. First, countries like Spain and Ireland were fast-growing, each with huge banking sectors that fueled asset bubbles and consumer spending that attracted record numbers of immigrants since the millennium–swathes of whom have been leaving since the bubbles burst. Then, there are the slower-growing, public sector-heavy Portugal, Italy and Greece. They have among the highest levels of public debt in the world and had rapid levels of immigration (though only about half of Ireland's or Spain's) over the past decade and similar outflows since. Finally, there are Europe’s largest economies: Germany, France, and the United Kingdom. These nations have had significant numbers of immigrants for longer, and though their immigrant populations remained roughly constant in the decade to 2008, national figures not yet finalized indicate that many have left since then.

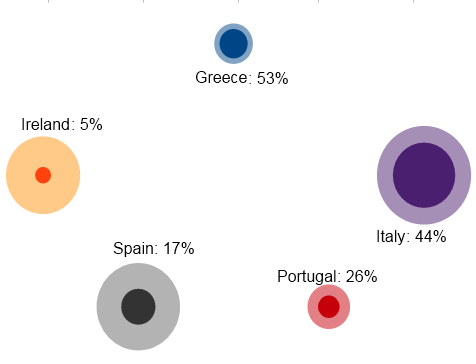

Large circles represent total debt, circumscribed ones the proportion, listed above, that is government-held

The reversals in net immigration levels in each country broadly mirror the amount and structure of its debt (See above image). Spain and Ireland, the countries with the highest level of private debt—held by banks, other companies, and consumers—experienced large contractions, the most dramatic shedding of jobs and consequently the largest immigration outflows. Portugal, Italy, and Greece, saddled with larger government debts both as a proportion of their GDPs and of their total debt, have experienced significant (though not as large) outflows.

The later onset of emigration in these latter three countries and their lower levels of immigration during the boom years owe to a root cause—and one not yet reflected in the 2008 OECD statistics just released. In Spain and Ireland economic contraction began earlier and unemployment levels shot up more quickly. This happened because growth and jobs in the two countries relied more on private capital, which dries up more quickly than public investment. With the high levels of government spending seen in Portugal, Italy, and Greece, the full impact of the recession on growth, jobs, and immigration remains to be felt. With cushier jobs in their bloated public sectors more often going to nationals, immigrants might bear less of the burden as the public sector cuts kick in.

–David Black

***

Tomorrow we look at Spain, perhaps the starkest and most telling example of the migration slowdown.