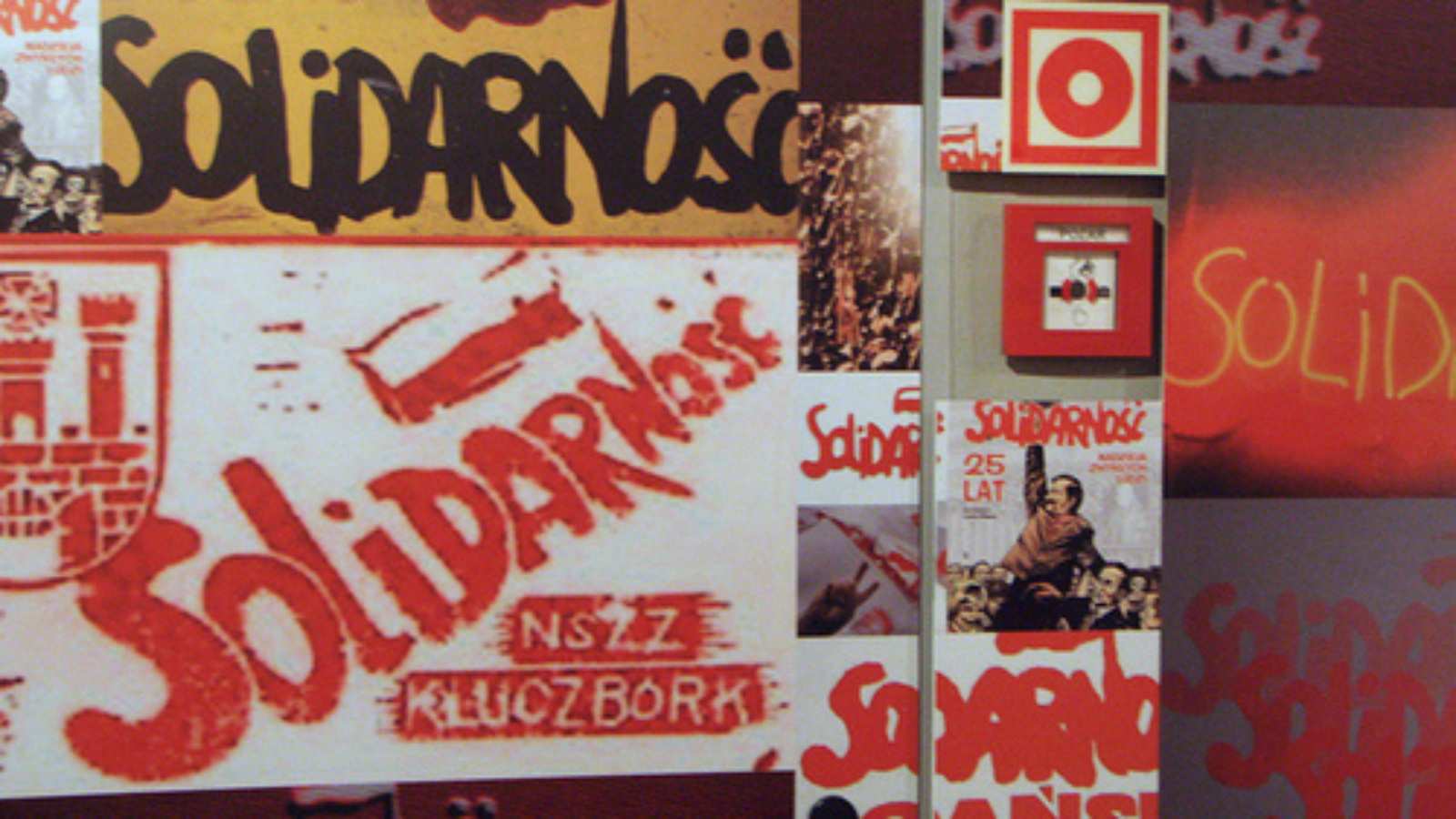

On August 31, Poland will commemorate the thirtieth anniversary of the Gdansk agreement that gave birth to Solidarity, the first independent trade union in the Soviet bloc. By staging strikes and occupying the Lenin shipyard, Lech Walesa and other activists pressured the communist government into legalizing their movement. Fifteen months later, the regime reversed itself, declaring martial law and outlawing Solidarity–but this only delayed rather than averted the looming crisis of the communist system. In 1989, the collapse of that system in Poland triggered a domino effect throughout the region.

Looking back at those events, we usually focus on the politics of those struggles rather than the economics. But it’s worth remembering that the abysmal state of the Polish economy was what fueled the protests from the very beginning. And it’s worth considering what that says about the relationship between economics and politics in America today, despite the enormous differences in these two situations. “Economic Security” is suddenly the hot term of the moment, with its implicit concern about economic insecurity—and the political fallout. This underscores one lesson from pre-1989 Poland that applies to the United States now: if you ignore or paper over underlying economic problems, you will eventually pay a high political price.

After the Soviet Union took over Poland and its neighbors at the end of World War II, the initial Stalinist-era repression gave way to a milder brand of communism. Protests that threatened the system were still brutally suppressed, but a tacit understanding developed: the rulers promised that the basic needs of their peoples would be met, with modest but steady improvements in living standards, so long as the ruled remained politically passive.

The centralized system insured that the gap between West and East kept growing, but the average citizen could get by—just barely. And officially there was no such thing as unemployment. As a popular saying put it, “They pretend to pay us and we pretend to work.” To maintain those pretences, Poland’s 1970s ruler Edward Gierek borrowed heavily from the West. This produced an illusory boom, but the infusion of capital had only boosted consumption or was wasted on nearly bankrupt state industries—or disappeared into the pockets of corrupt officials. Throughout the 1980s, Poland was a basket case, with $40 billion in foreign debt, an inflation rate of Latin American proportions, and rationing combined with shortages of everything from basic foodstuffs to medicine. A young couple could expect a waiting period of anywhere from twenty to forty years to get an apartment, and hospitals began running out of anesthesia for some routine operations. Little wonder that the young were increasingly ready to risk everything to follow Solidarity leaders like Walesa.

To be sure, the American and most European economies still operate on a far more rational basis than the pre-1989 economies of Central and Eastern Europe. And the good news is that the polnische wirtschaft—German for the Polish economy—is no longer a term of derision precisely because Poland now operates according to free market principles. Last year, Poland was the only EU country to register positive economic growth, and the country is almost unrecognizably different and dramatically more prosperous than its earlier incarnation.

Where there is a connection between the Poland of the old days and the United States today is the heightened awareness that governments must create conditions that give their citizens a sense of economic security. The failure of communist regimes to do so at the most basic level led to their eventual collapse. If Americans begin to feel that their economic system can’t provide a degree of security for their much higher living standards, the consequences won’t be as spectacular as the upheavals of 1989. But they shouldn’t be underestimated either.

Budgets are produced that don’t come close to suggesting a course that will curb the country’s addiction to massive deficit spending, China keeps underwriting us to an unhealthy degree and basic decisions on applying common sense solutions are shelved repeatedly because there’s always another election coming up. And, of course, politicians from both parties always blame their opponents for the fact that nothing serious is getting done.

The rap on Democrats is that they never encountered a spending proposal they didn’t love, and on Republicans that they never saw a tax cut they didn’t adore. That may be oversimplifying, but not by much. In the meantime, yet another presidential commission will study the problem.

The reason the term “economic security” is gaining acceptance is precisely because there’s the sense that, with every passing day of inaction, our economy is increasingly insecure. You can pretend that’s not the case, as Poland’s leaders tried to do for a long time. Or you can start tackling the fundamental problem of how we can start living roughly within our means. Solidarity’s 30th birthday party offers a clear indication which is the better course.

Photo via Flickr, user Bret Arnett.