by Richard Horowitz

The world has good reason to be concerned about Iranian decision making, whether with respect to its nuclear program or the possible stoning of an Iranian woman, and the vast bulk of these decisions have as their roots, all but ignored outside the nation, the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran. [A detailed analysis examining many of the articles of this document is available by clicking here.]

a detailed analysis, examining numerous articles

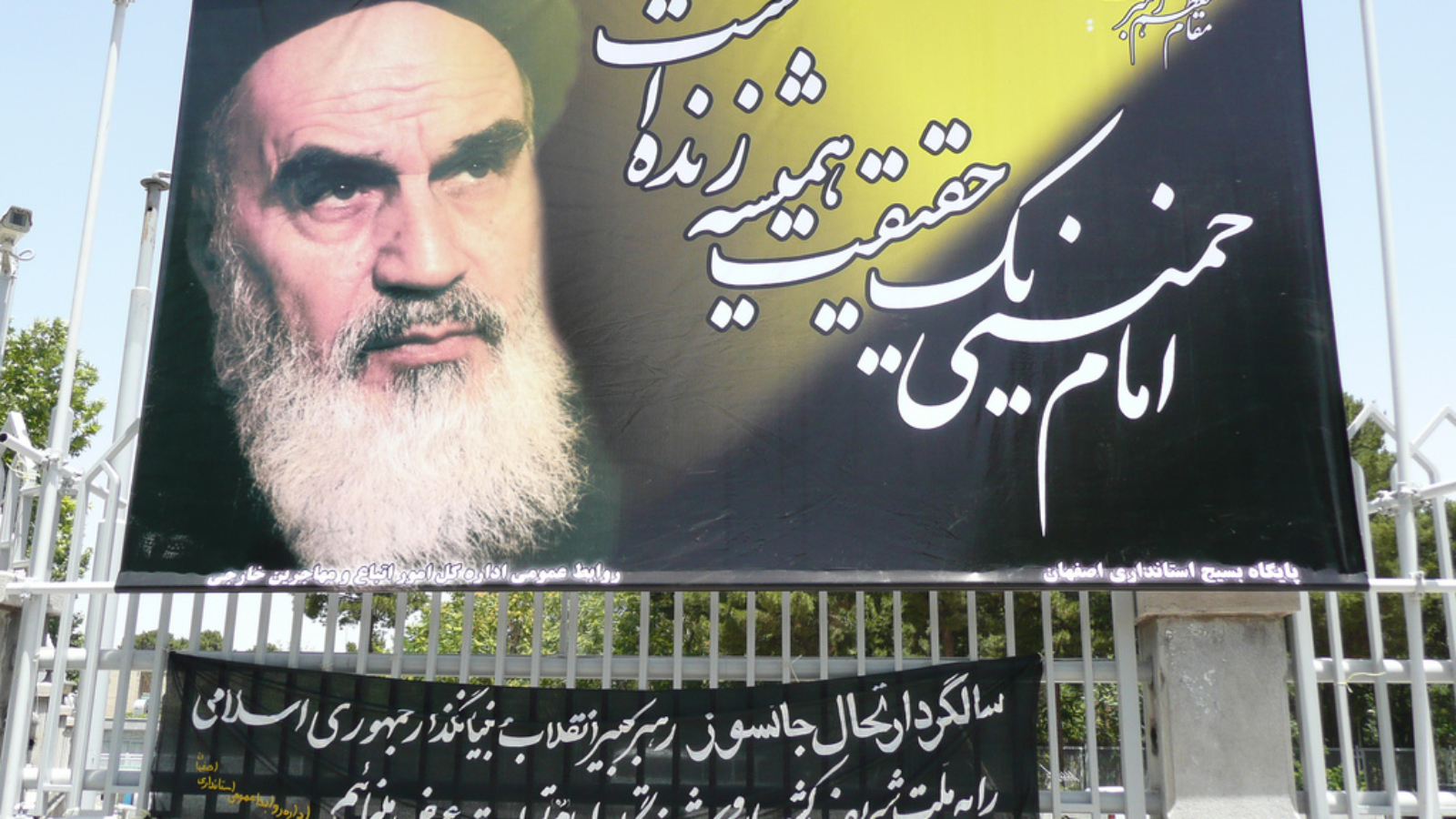

Commentators have tried to explain the current Islamic Repubic since its inception. On February 16, 1979, just 15 days after the Ayatollah Khomeini returned to Iran from France after the fall of the Shah, Richard Falk, currently the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights on Palestinian Territories Occupied Since 1967, published an Op-Ed piece in the New York Times entitled “Trusting Khomeni.” Falk noted that President Carter and National Security Advisor Brzezinski “have very recently associated him [Khomeni] with religious fanaticism” and claimed that “the news media have defamed him in many ways, associating him with efforts to turn the clock back 1,300 years, with virulent anti-Semitism, and with a new political disorder, ‘theocratic fascism,’ about to be set loose on the world.”

Falk closed his article by writing that “Iran may yet provide us with a desperately-needed model of humane governance for a third-world country.” The new Islamic Republic of Iran adopted its constitution eight months later and understanding this document is crucial to understanding Iran.

Parts of this Iranian Constitution sound familiar. Take, for instance, the first clause of Article 57: “The powers of government in the Islamic Republic are vested in the legislature, the judiciary, and the executive powers.” Further, every citizen can seek justice through the courts, defendants are presumed innocent, and evidence obtained under torture is inadmissible. Some articles seem laudable: All people of Iran enjoy equal rights and the investigation of individuals' beliefs is forbidden.

But the immediate departures hold within them the potential for the extraordinary abuses of human rights that have been undertaken in this document’s name. The continuation of Article 57 which establishes the Iranian legislature, judiciary, and executive powers dictates that they are to “function[ing] under the supervision” of Iran’s Supreme Leader. The constitution further requires its president to swear to “dedicate [himself] to the propagation of religion and morality” and members of parliament to swear “to protect the sanctity of Islam.” The document requires Iran’s flag to contain the phrase “Allahu Akbar,” states that “Absolute sovereignty over the world and man belongs to God,” an established a Guardian Council “in order to examine the compatibility of the legislation passed” by its parliament with Islam.”

Numerous constitutional provisions are required therefore to be “in conformity with Islamic criteria” or not “detrimental to the principles of Islam”—among them, human rights and equal protection of the law, the formation of political and professional associations, and public gatherings, and freedom on the press. The Iranian Constitution cites Quranic verses fourteen times, as the constitution makes clear its objective to promote Islam worldwide—its preamble stating that the constitution “provides the necessary basis for ensuring the continuation of the Revolution at home and abroad.”

Military powers is also carefully spelled out, their roots again in the Quran. Its Army and Revolutionary Guard “will be responsible . . . for extending the sovereignty of God's law throughout the world and that Iran’s foreign policy “is based upon the rejection of all forms of domination”—worldwide. Moreover, here, as in other provisions, the document further provides an historical context: “The plan of the Islamic government as proposed by Imam Khumayni [under the Shah] . . . [gave] greater intensity to the struggle of militant and committed Muslims both within the country and abroad.”

The roots of the Iranian Constitution are found in a book written by Ayatollah Khomeini in 1970 entitled Velayat-e Faqeeh, or Governance of the Jurist. And the underlying argument of this work is that the Islamic scholar must rule an Islamic state. It is the Islamic scholar who should rule an Islamic state – the source for Iran’s Supreme Leader. According to Khomeini, “Islam proclaims monarchy and hereditary succession wrong and invalid” . . . The form of government of the Umayyads and the Abbasids . . . were anti-Islamic.”

Having established the Quranic basis for governance by a jurist, Khomeini indicates how this governance will be applied: “But when Islam wishes to prevent the consumption of alcohol . . . stipulating that the drinker should receive eighty lashes, or sexual vice, decreeing that the fornicator be given one hundred lashes (and the married man or woman be stoned), then they start wailing and lamenting.” Khomeini was also a proponent of amputations; the Islamic jurist as ruler must be able to say the we want a leader “who will place his own family on an equal footing with the rest of the people; who will cut off the hand of his own son if he commits a theft; who will execute his own brother and sister if they sell heroin.”

The Iranian constitution has not existed in a vacuum, however. Through the years, American courts have had reason to review and scrutinize aspects of the Iranian Constitution.

In 1984 a federal district court in Missouri ruled that “the Islamic revolution and subsequent rise to power of clerics in Iran has so thoroughly affected” Iran’s legal system that it would be “unreasonable” to require [an American company] to stand before an Iranian court, citing, among other evidence, Article 4 of the Iranian Constitution, that all Iranian law must be based on Islamic standards. The ruling was upheld on appeal to the eighth circuit Court of Appeals a year later.

American courts have granted political asylum to Iranians, citing various State Department reports, for example, that “beatings are routine in Iran and that religious minorities not recognized by the constitution of Iran are persecuted,” and while the [Iranian] Constitution forbids the use of torture…there are numerous, credible reports that security forces and prison personnel continue to torture detainees and prisoners.”

U.S. courts have also found Iran responsible for the bombing of the marine barracks in Lebanon in 1983 that killed 241 marines. Quoting the Iranian constitution that “provides the necessary basis for ensuring the continuation of the Revolution at home and abroad,” a federal court concluded that “The post-revolutionary government in Iran thus declared its commitment to spread the goals of the 1979 revolution to other nations. Towards that end, between 1983 and 1988, the government of Iran spent approximately $50 to $150 million financing terrorism in the Near East.”

The current Iranian government is an Islamic theocracy with global intentions. Numerous constitutional provisions make Iranian law subordinate to its Islamic interpretation. If Iran sees an Islamic imperative, its constitution and legislation will be interpreted accordingly.

Iran’s constitution provides that “while scrupulously refraining from all forms of interference in the internal affairs of other nations, it supports the just struggles of the [oppressed] against the [tyrants] in every corner of the globe,” allowing Iran to make its claim that it has never executed an offensive attack on foreign soil—when in fact it does so through proxies, whether the bombing of the marine barracks in 1983 or killing Americans today in Iraq.

Those who support the approach that “we will extend a hand if you are willing to unclench your fist” may want to consider that in 1970 Khomeini wrote that one of the responsibilities of the governing jurist is to “foreshorten the arms of the transgressors who would encroach on the rights of the oppressed” and should note that the closing sentence of the Iranian constitution’s preamble expresses “the hope that this century will witness the establishment of a universal holy government and the downfall of all others.”

Richard Horowitz is an attorney in New York concentrating in corporate, international, and security matters and is the founder and editor of InternationalSecurityResources.com.

Picture via Flickr by bezoire.