by Robert Valencia

The national newscasts dedicated hours of coverage to one of the most significant strikes in the history of the Colombian military against the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, better known as FARC. Its legendary leader, Victor Julio Suárez Rojas, also known as “Mono Jojoy” was killed by the Colombian authorities during a raid the Santos administration named “Operation Sodoma” on September 22, 2010, in the Macarena region, 120 miles south of Bogotá.

Along with the landmark “Operation Checkmate,” which helped release several American hostages and former Colombian congresswoman and presidential candidate Ingrid Betancourt—the poster child of a six-year ordeal—the September military operation has also come to be viewed as one of the most efficient in Colombia’s history. That this evaluation is even possible is due in a large measure to confidential information provided by snitches inside the insurgency, who helped install a chip in Jojoy’s boots, which made it easy for smart bombs to track and kill him. Indeed, the success of these military operations has built the hopes of a prosperous, peaceful Colombia among its citizens and bolstered the self-esteem of the armed forces.

What’s more, the recent decision of Colombian inspector-general Alejandro Ordonez to ban Senator Piedad Cordoba from ever holding office again is considered, by some experts and the public eye, as yet another blow against the FARC in the realm of politics. Cordoba, 55, has been a controversial figure in Colombian politics due to her agitation for establishing peace talks with the FARC and her alleged close personal relationship with some of their leaders. While she denied supporting the FARC, Ordonez said he has evidence that she “tried to improve their strategy and reaching their objectives” and other activities as described on the computers recovered after the killing of another FARC leader, Raúl Reyes.

There’s little doubt that these events signaled yet another step in the collapse of the oldest Marxist armed forces of the Western Hemisphere as its approval ratings among Colombians has been on a steady decline. However, it’s dangerous to underestimate the present danger that FARC still poses. On August 12, five days after the inauguration as president of Juan Manuel Santos, a car bomb partially destroyed the Caracol Radio facilities in the Financial District of Bogotá and inflicted several injuries on at least nine people. Then on October 11, the insurgents toppled one of the communications towers in the southern state of Cauca, leaving more than 500,000 people without connection.

What’s more, FARC still numbers 10,000 members and collects profits from drug trafficking and ransom, while maintaining a dynamic international relations platform—recognized as most effective by former president Alvaro Uribe and which has won European support from groups like the Denmark-based “Fighters and Lovers.” Moreover, it’s alleged that some of its bases are located in the jungles of Venezuela, which has raised diplomatic and economic tension between the two countries in the last two years.

So can Colombians envision a free-guerrilla, more prosperous country? It seems that the “democratic security” doctrine set up by former president Uribe has yielded some benefits—despite the highly controversial “false positives” case in which the army has been shown to have murdered civilians who were then dressed in rebel uniforms or given guns and presented as guerrillas or paramilitary forces killed in combat. Uribe’s initiatives have built confidence in the international community, not only among foreign investors. On October 12, Colombia clinched one of the temporary seats to the United Nations Security Council for the 2011-2012 period to represent Latin America and the Caribbean, a success that President Juan Manuel Santos called “a great [international] recognition to our country.” Even though Colombia’s representation—alongside Brazil’s— was practically guaranteed by the Latin American and Caribbean Group, Colombia received substantial support from the broad international community. Some 186 countries out of 191 approved of Colombia’s provisional membership in the Council. In fact, the nation’s presence in such international arenas will surely pay off by way of showcasing its expertise on combating terrorism. Already Colombia offered help to strengthen Afghanistan’s beleaguered security system last January.

It’s also important to note that Colombia is recognized not only for its success in combating terrorists, but also in economic matters. Three years ago, Businessweek named Colombia as the “most extreme emerging market” on the planet. Today, even in the face of the worst global recession since the Great Depression, Colombia has proved to be resilient thanks to its fiscal policies. Most recently, HSBC CEO Michael Geoghegan labeled a new group of emerging markets the CIVETS—or the next BRICs—which are comprised of Colombia, Indonesia, Vietnam, Egypt, Turkey, and South Africa. Each of these countries, he observed, have all the elements in place to become economic powerhouses and lead the global recovery—a young and growing population, dynamic economy, and political stability.

Colombia is making strides to foster socioeconomic progress. But it is too early for any self-congratulation. Even if the current and future administrations put an end to the leftist insurgency by force or by way of peace talks, lingering social inequities will always fuel instability. Unemployment hovers at 11.7 percent—one of the highest in Latin America. Nearly half of all Colombians live below the poverty line, peasants are still being forced out of their homes by the four decade-long armed conflict, and growing street gang violence grips cities like Medellín and Cartagena. The time to level the playing field for a post-guerrilla Colombia is now, and the Santos administration is well aware of this. Finance Minister Juan Carlos Echeverry recently declared at an International Monetary Fund meeting that the government hopes to develop a middle class, create 3 million jobs, cut poverty by improving the lives of 7 million people, spur development in R&D, mining, agriculture and exports, and expects the economy to grow at a steady 6 percent annual rate over the next decade.

As former finance minister Rudolf Hommes said regarding this administration’s blueprint: “It costs nothing to dream, but in order to make dreams come true it is necessary to count on money, teamwork and an unswerving political determination to respond to the zeal this administration’s plan has generated.”

Robert Valencia is a research fellow of the Council on Hemispheric Affairs.

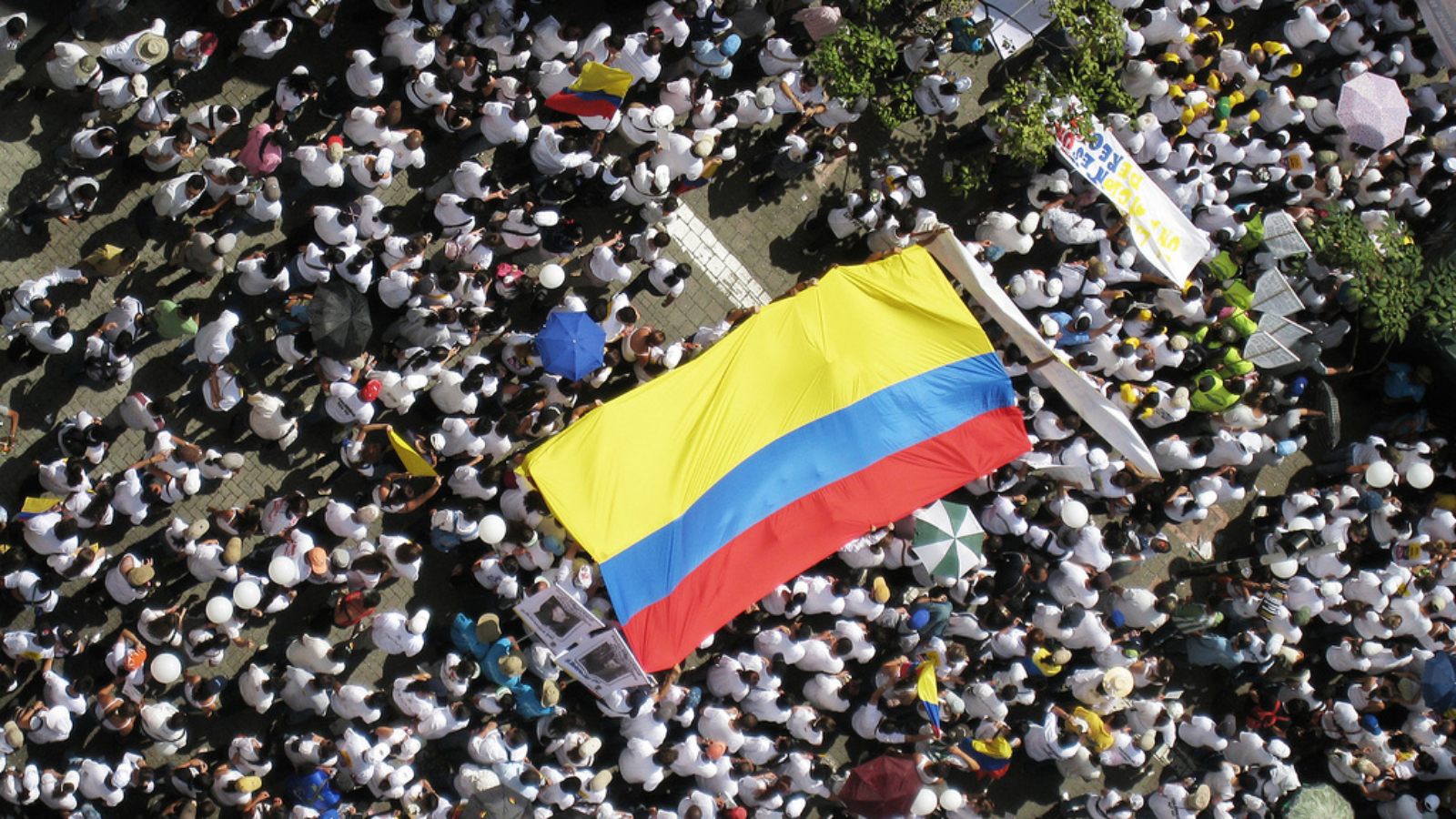

Photo via Flickr, by xmascarol.