By Evan Gottesman

Numbering just over 450,000, French Jewry represents the third largest community outside of Israel and the United States. The republic may be at risk of losing that title. On January 9, 2015 gunmen killed four people at a kosher grocery in Paris. After the murders, France’s Prime Minister Manuel Valls declared that if Jews leave the country en masse, “The French Republic will be judged as a failure.” The authorities dispatched 10,000 troops to secure Jewish sites across the country. However well intended, such sentiments may be too little, too late

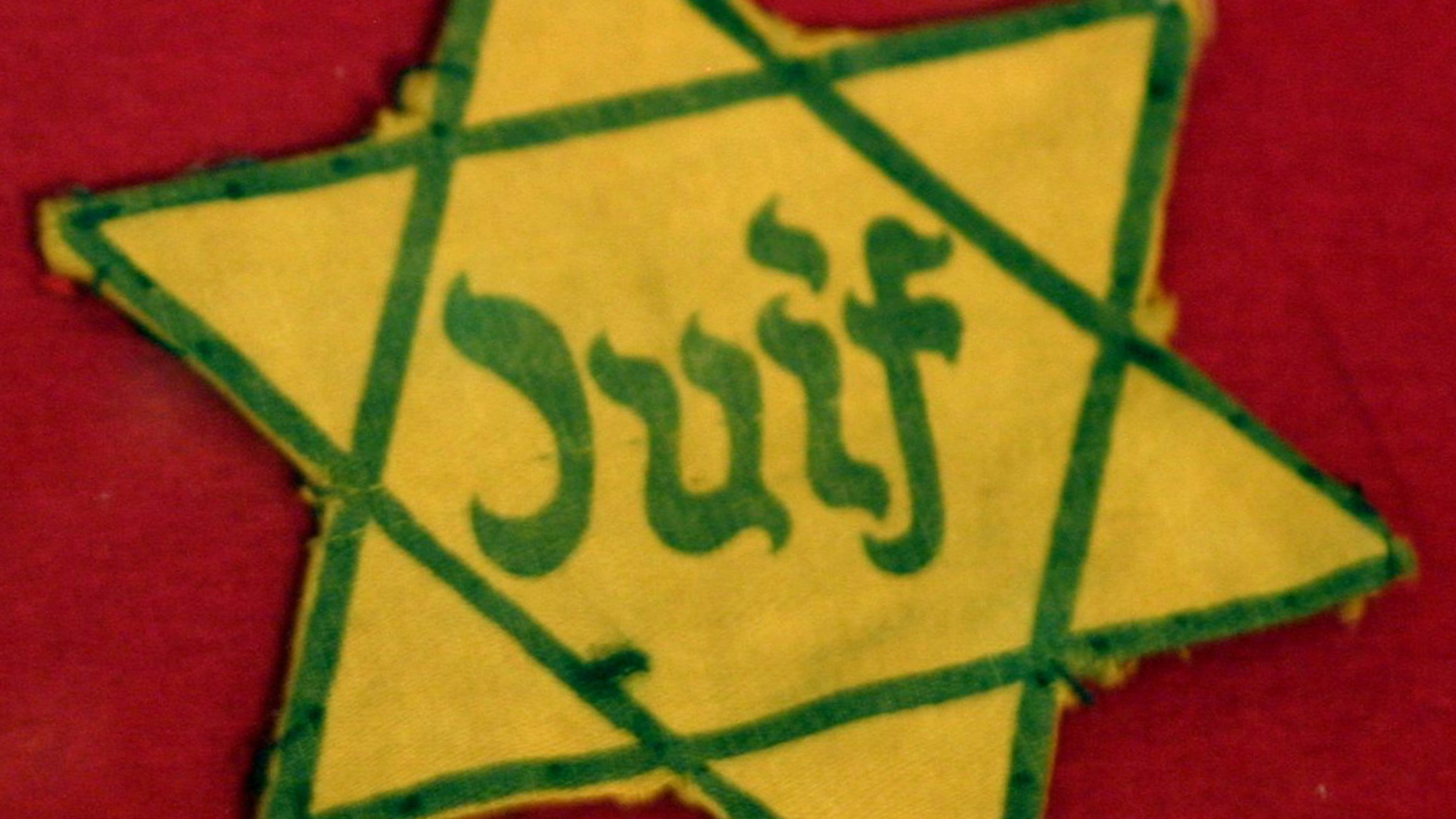

Last week’s tragic events in Paris brought anti-Semitism back to the fore, but those events were hardly isolated incidents. France and the Jewish people have a troubled relationship. During the French Revolution, the country became the first in Europe to grant Jews citizenship. Yet, France was also the scene of the Dreyfus Affair, when a young French army captain of Jewish descent was wrongly accused of espionage and imprisoned. During World War II, many French leaders acted as willing participants in the Holocaust. Today, Islamic extremism and Muslim-Jewish tensions, colored by the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, suggest a new face of French anti-Semitism. However, beneath this unrest, the far-right old guard—hostile to Jews and Muslims alike—persists and indeed has become ever more visible. The two extremes—traditional rightist groups and Islamist fundamentalists pose a grave threat to French Jewry. Whether the French government can deal with this far-reaching problem is unclear.

The assailant in the January 9 attack on the kosher supermarket was an Islamic extremist, yet this was hardly an isolated incident. Last August, two teenage girls, members of a fundamentalist Muslim terror network, targeted the Great Synagogue in Lyon in a failed suicide-bombing plot. Arab immigrants from North Africa and the Middle East were behind most of the riots that rocked France’s Jewish neighborhoods during the summer months. In July, a firebomb exploded at the entrance to a synagogue near Paris. The incident, like last week’s murders, occurred on a Friday—the start of the Jewish Sabbath. Elsewhere rioters callously staged violent demonstrations on the anniversary of the 1942 Vel d’Hiv roundup, the mass-arrest of Parisian Jews by French police during the Holocaust. These demonstrators looted and burned cars in the name of protesting Israel’s war in the Gaza Strip. The significance of these dates belies a deeper, more insidious and anti-Semitic motive. Tellingly, 2014's string of anti-Jewish disturbances in France began well before the Gaza conflict. French authorities responded to the violence by banning the anti-Israel rallies that bred violence in the country’s Jewish population centers. The measure was hollow. It failed to ease communal tensions between Jews and Muslims. It did not make Jews safer or less hated. It only quieted some anti-Semites, and then only briefly.

While this month’s murders and last summer’s violence made major headlines, Arab rioters and Islamist fundamentalists are hardly the only villains in this story. The National Front (FN), France’s third largest political party, is another threat to the country’s Jews. The far-right movement has a long history of anti-Semitism. In 2011, the party’s leader, Marine Le Pen, told Israeli newspaper Haaretz that she would “definitely not” have denounced Marshal Henri-Philippe Pétain’s fascist government and called President Jacques Chirac’s 1995 apology for France’s crimes in World War II “a mistake.” The authoritarian French government that Pétain headed sent some 80,000 Jews to Nazi concentration camps, primarily on its own initiative. Only 2,000 survived. More than 70 years after Vichy’s fall and the genocide of European Jewry, the intolerance that sustained Pétain’s leadership remains a fixture in French electoral politics. The FN finished first in France’s 2014 European parliament elections.

French Chief of State Henri Philippe Pétain (left) meets Adolf Hitler (right) in October 1940.

If President François Hollande and his ministers want to retain their country’s Jewish population, France will need to confront its Holocaust legacy once again. It is doubtful that Hollande will do so, for it would require him to challenge Le Pen and her right-wing supporters, while his support continues to plummet. The FN chief is confident her following will expand as French public opinion aligns ever closer to her party’s Islamophobic platform in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo attack. Anti-Semitic violence by French Arabs also plays directly into the National Front’s narrative, as the FN promotes deportation for legal immigrants who commit crimes in France. This confluence of interests offers a dismal scenario where both French Jews and Arab Muslims endure the reactionary and oppressive politics of intolerance.

These trends are having an impact. Annual French Jewish immigration to Israel tripled in the past three years, with 7,000 arriving in 2014. Of these, over 1,300 came in July—during the Gaza War. As Israeli authorities embraced their French kin, the Jewish state’s President Reuven Rivlin adopted a more sober tone, lamenting the circumstances that provoked the spike in immigration. “It is important,” Rivlin remarked after the January killings, “that this aliyah [Jewish immigration] to Israel will not be an aliyah of fear but an aliyah of choice, an aliyah born out of a positive Jewish identity, out of Zionism, and not because of anti-Semitism.”

The murder of four French Jews on January 9 was disturbing. It was tragic. It was also nothing new. This time, the criminals themselves may have been Arab and Muslim. However they are part of a longstanding and increasingly disturbing trend. The old forces of European anti-Semitism are not absent in France. The fear is that France is becoming a country that needs thousands of soldiers just to protect its Jewish citizens. While the security lockdown may be necessary in the immediate aftermath of January’s attacks, no French army, regardless of its size, will ever cure anti-Semitism. Such an undertaking will require more than France has yet offered.

*****

*****

Evan Gottesman is an editorial assistant at World Policy Journal.

[Photos courtesy of Wikimedia Commons]