(Subscribe to World Policy Journal here)

From the Spring 2015 issue "The Unknown"

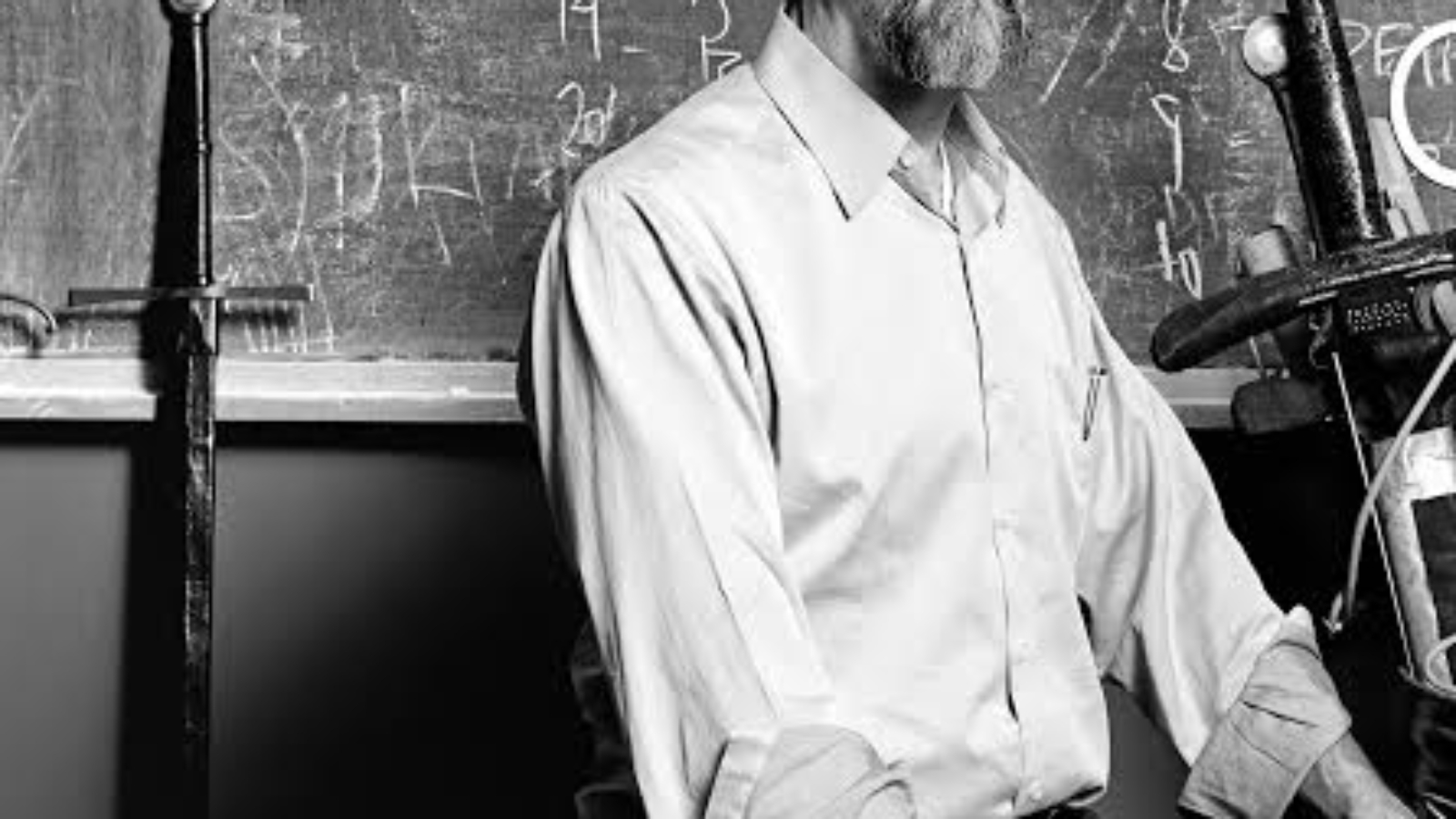

Neal Stephenson is a visionary. One of the world’s premier authors of science fiction, he sees both visions and a future that are unlike any most of us will ever imagine. At times, they find their way into his remarkable books—especially his latest and most dramatic, Seveneves, due out in May from William Morrow. At other times, we are enriched by his thinking about future realities, which he is quite careful to distinguish from his fiction. Four years ago, Stephenson bemoaned in our Innovation issue the lack of any recent invention that had altered our core landscape. This time, he’s joined World Policy Journal editor & publisher David A. Andelman and managing editor Yaffa Fredrick in our Chat Room to reflect on the The Unknown.

WORLD POLICY JOURNAL: Your life seems to have been built around the future, your work a succession of examinations of worlds far into the future. So tell us what you see as the greatest single unknown we may be heading toward?

NEAL STEPHENSON: If I could channel Donald Rumsfeld for a second, it’s certainly the unknown unknowns. It’s the things that come out of nowhere, that don’t get predicted by people whose job is to predict things. The classic example I like to cite is the electric guitar and the global dominance of music that is based on the electric guitar. When electricity was invented and popularized, everyone predicted that we would build light bulbs and labor saving machines. But I don’t think anyone anticipated that we would have electric guitars. Certainly they couldn’t foresee that electric guitars would be adopted by different groups as the basis of a new kind of music and that music would become enormously popular. So that is the example of an unknown unknown that worked out in a very favorable way to produce a new kind of culture nobody expected, and it had a happy ending.

WPJ: The last time you wrote for us, you observed that there hadn’t been anything really dramatically new invented in probably a hundred years. Since the airplane, or electricity, or the telephone, everything since has been a kind of refinement. The electric guitar is essentially a refinement of the guitar and a refinement of electricity, but it’s not dramatically new. Do you see something new coming along that we will say, “that is going to change civilization”?

STEPHENSON: Well I think [the electric guitar] did change civilization. What you are referring to is more a statement about things that changed the built landscape that we live in, that creates entirely new categories of infrastructures and new ways of moving around. I do believe that the last decades have given us very little of that kind of innovation. All the brain power that used to go into building rockets and hydrogen bombs and jet airplanes has gotten shunted in the last decades into the production of information technology, and that’s fine but…

WPJ: …So then do you see the principal future challenges coping with differences in religion, disparities in wealth, scarcity of resources, or perhaps some toxic mix of all of these unknowns? Is that what we’re going to be dealing with—large transformational ideas rather than creation of things?

STEPHENSON: I think the idea ecosystem doesn’t really change much. The ideology behind IS is a virulent ideology. It’s having powerful effects, but I don’t see anything there that’s particularly new. It’s a cross between a particular point of view about Islam and maybe some 20th century ideas about politics. I don’t think the landscape of ideas really changes that rapidly.

WPJ: Will some magic wand resolve any such issues, or is mankind in a perpetual series of endless conflicts that effectively ping-pong back and forth between minor crises that threaten to explode? Is there some unknown that could effectively become a universal panacea?

STEPHENSON: The ideologies that are the most troublesome have been fundamentalist ideologies of one kind or another. Sometimes they’re religious, sometimes they’re secular, but what they seem to have in common is that for people who like things very simple, they provide a simple explanation for what’s going on—who the bad guys are, who the good guys are—and give people the justification they are looking for to go out and kill the bad people. Those are the most dangerous ideologies that we’ve seen in different forms for a long time now. There are obviously places in the world where ideologies like that are rampant today. But there’s evidence supporting the idea that the Internet overall tends to expose more people to a broader range of ideas. It’s a little tricky because the Internet also creates little bubbles, little pockets where you can just get caught up and talk to people who are like you or agree with you. There are a lot of examples of that.

I still believe in the overall trend—that as people get exposed to a broader range of things on the Internet that tends to reduce the power of absolutist ways of thinking. A lot of the really strident kind of fanaticism we’ve seen in some quarters now is a reaction against that—creating a kind of awareness on the part of some people that they are facing a challenge in the form of globalization that is probably going to defeat them in the end and has to be fought back against with kind of last ditch measures.

WPJ: You talk in your new book, Seveneves, about the Earth itself becoming a ticking time bomb 5,000 years in the future. Now we know that mankind has existed already on earth for 5,000 years. So is it your view that mankind will survive as a race, or are we condemned eventually to extinction?

STEPHENSON: There are very few eventualities that could kill everyone. In Seveneves, what I’m doing is positing a particular kind of global disaster that actually does have the potential to wipe everybody out. But it’s a “what if” kind of scenario, and there’s nothing to believe that it’s probable. It’s strictly a science-fictional conceit. Maybe 20 or 30 years ago, Jonathan Schell in The New Yorker was arguing that global thermonuclear warfare could kill everyone in the world, and it was used as a very powerful argument for disarmament.

WPJ: We could kill everyone or make the entire planet effectively uninhabitable for a very long period of time.

STEPHENSON: Right, but Schell had to work pretty hard to develop that case. You can always argue that people are going to find a way to survive, in underground bunkers or what have you. People can be quite ingenious when they are forced to do so. So, barring some kind of astronomical disaster, something that comes from outside of this planet, which is exactly what I’m positing in the opening pages of Seveneves, I think people always find some way to survive.

WPJ: But that doesn’t seem out of the realm of possibility. We hear stories about enormous asteroids that could even knock our planet out of its primary orbit.

STEPHENSON: Oh yes, and there’s the possibility of gamma-ray bursts, nearby supernovas that could hit us with radiation that could sterilize the planet.

WPJ: But the human mind is so inventive that there could be an unknown that we could develop to counter that, that makes extinction less likely?

STEPHENSON: Seveneves is a thought experiment. What if the population were reduced to almost nothing and had to be filled back again. That’s what makes it science fiction as opposed to science-prediction. That’s a fanciful aspect of the story if you will. But it shouldn’t be confused with a serious effort to talk about our future.

WPJ: Let’s talk about our next nightmare. In your last book, Reamde, you combine Chinese cyber-criminals, Islamic terrorists, and Russian mafia—every one of our contemporary nightmares. What’s our next nightmare we may not even have considered yet?

STEPHENSON: There’s the well-known stuff like smallpox. There’s dirty bombs—those kinds of highly damaging events that could be unleashed by a malicious actor somewhere, but I think the real one, the one people should be paying attention to, is climate change, which is going to happen. I mean there is absolutely no way that massive climate change will not occur. If you run the numbers, if you look at how much carbon dioxide we’ve put into the atmosphere, it’s just blatantly obvious that there is no conceivable program of geo-engineering or emissions reduction that would truly make a difference. I wish it were otherwise, but the numbers tell a pretty clear story. We’re sort of left with geo-engineering, but for very political reasons geo-engineering isn’t going to happen either. So we’re going to have huge climate change. Everything is going to be different. There’s going to be enormous shifts in population and economic activities as the result of that. A few people might benefit from it; most people won’t. And it’s going to happen kind of relentlessly over a period of centuries. The story of the next few centuries is the inevitability of global climate change and how people are going to respond to it.

WPJ: Is that already irreversible in your view?

STEPHENSON: Yes. I sat down with some people a few years ago to try to think about carbon sequestration and what it would take to extract a significant amount of carbon back out of the atmosphere, and the numbers were just insane. Effectively you’re talking about taking every coal mine and every oil well and every natural gas well that has ever existed, and running it backwards full tilt for centuries to take the carbon out of the air. We can talk about tax credits or carbon market or something like that as a way to provide some economic incentive for people to do that, but it would take a preposterous amount of money to actually make any advance in the problem.

WPJ: Is that what keeps you up at night, if anything does?

STEPHENSON: Climate change is going to be slow. It is going to take a long time. It doesn’t mean people are not going to get seriously hurt by it, but it’s not something like global thermonuclear warfare, which could happen in the blink of an eye basically, and not give people any time to react to it.

WPJ: You are now Chief Futurist of a company called Magic Leap, seeking the ultimate in augmented reality. Isn’t that effectively a contradiction in terms? Reality is simply reality?

STEPHENSON: We all spend a significant amount of our days now looking at pixels. I look at photographs of my work environment from only a few years ago, and I see giant cathode ray tubes. I had to build massive supports, just to hold them up. Those disappeared over a very short span of time and were replaced by flat screens, and almost as quickly we got iPhones and iPads and we began carrying these things around with us to more conveniently look at pixels. So we’re not going to stop looking at pixels anytime soon, and so the question just becomes what’s the best way to do that. There is no reason to assume that the devices we use today are any more permanent in the landscape than giant cathode ray tubes were 10 or 15 years ago. So, eventually it seems inevitable that we’re going be using wearables for this purpose, and then you get into various approaches to wearable displays and additionally those have been divided into two categories, virtual reality and augmented.

Virtual just means that essentially everything you see, every photon that touches your retina is being generated by this device, and you’re not seeing anything of the actual world. Augmented usually means that you’re seeing both—photons that are coming from your surroundings, but you’re also seeing a few extra photons that are being somehow projected into your eyes by your wearable device. What Magic Leap is working on is in the latter category. It is sufficiently more advanced than traditional augmented reality displays that the company prefers to call it by a different name, which is cinematic reality. It’s in the category of things that add photons to your view of the world rather than completely replacing your view of the world.

WPJ: Once you have achieved the creation of something that is absolutely as perfect as your eye can see it, what is left to create?

STEPHENSON: I’m not super concerned about reaching that level of perfection anytime soon. I think there is always going to be ways to improve on what we’ve got. In the case of what Magic Leap is doing, a tool for relating to information, I think it is going to be improvement on what we’re doing now. Instead of being hunched over little screens and staring at rectangles, we will be interacting with information in a way that is a better fit for the way our eyes evolved. And that involves less eyestrain, less mental strain. There’s always ways to improve.

I’ll make a hypothetical example. If aliens showed up tomorrow and dropped the most perfect imaginable user interface devices in our laps and gave us free copies for everyone, we could then spend the next several centuries just trying to figure out how to make content to run on that device. It would stop becoming an argument about technology and become an argument about culture. As much as I would love to nerd out on the pure hardware aspect of it, it turns out it’s being handled by really smart people. So, by process of elimination, I’m there to think about content. Content is an inexhaustible source of challenges because there is no limit to what kinds of creative uses people will put this to.

WPJ: Well that seems to sum up the future. Thanks so very much for joining us.

*****

*****

[Photo courtesy of Kyle Johnson]