By James H. Nolt

Ordinary people know the phrase “money talks” and are often more savvy about the influence of money than many social scientists. I will interrupt the flow of my topics as promised last week because sometimes there are news stories that grab my attention. Including both this week and last, there were four headlines having to do with the influence of money power, though otherwise they are rather different.

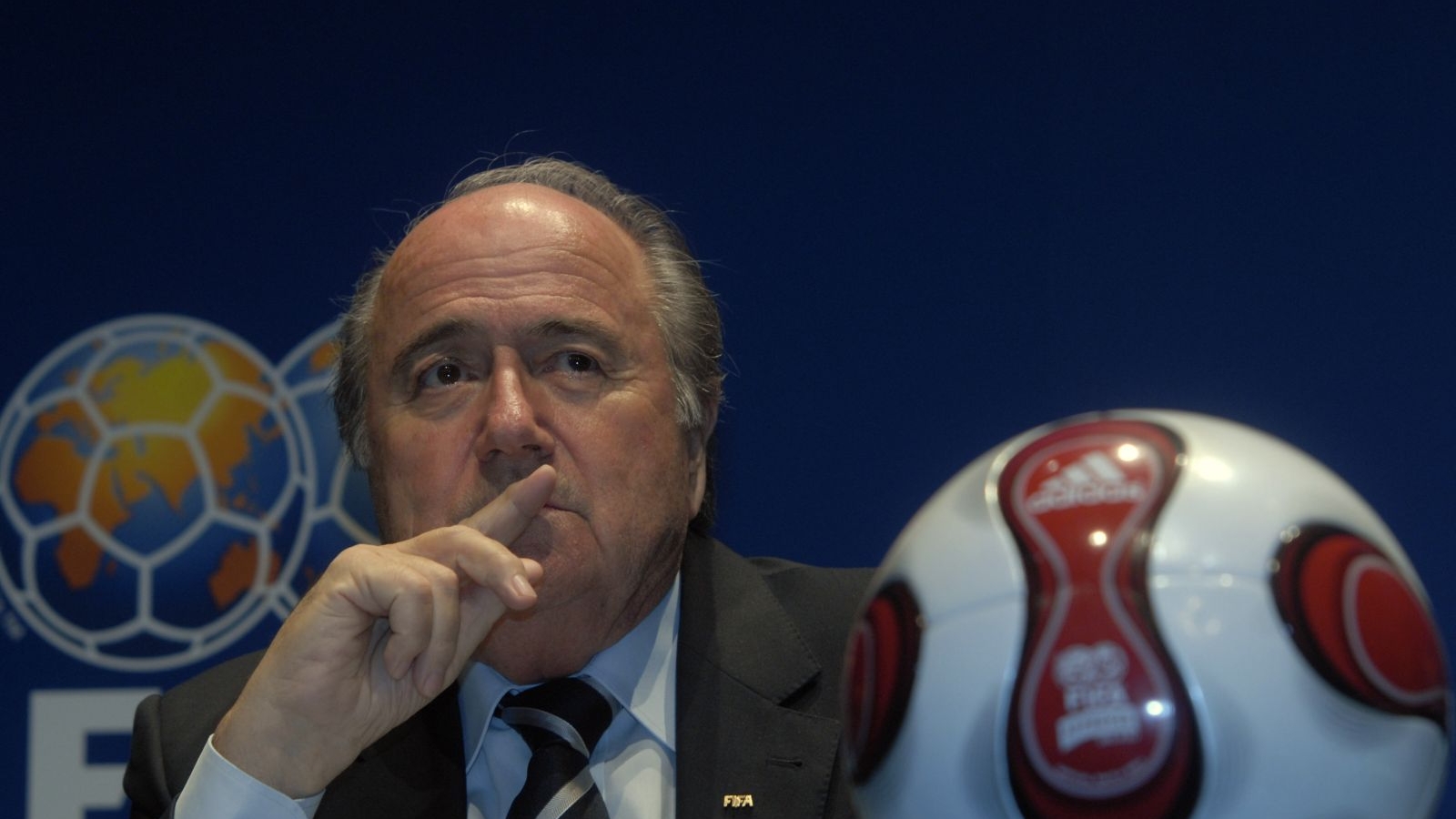

Let’s start with the latest and most obvious: sport is big business, often corrupt. More than two decades ago, I assigned my students in a course on “business power in politics” at Vanderbilt University to each research a different industry and describe any cartels and how they operated. Whereas most economics textbooks say cartels are unusual and unstable, that is not what my students found. They researched dozens of different industries worldwide and not one of them came back to me and complained that finding cartels is difficult. They are everywhere organizing against the mythical free market of economists.

My students wrote many good papers, but one stuck in my mind because until then I knew nothing about the business he researched: international soccer (or football, as most of the world calls it). Thus my only surprise at the arrests and indictments of soccer officials this week was not that corrupt schemes were discovered, but how long it took for investigators to catch up with illegal behavior my students already identified in a semester term paper over 20 years ago.

An even bigger incident last week, but harder for most people to understand, is that several big banks were fined last week for a pattern of years of fixing foreign exchange trading. The fines negotiated with regulators, ranging into the billions of dollars, sound like a lot of money to most people. But considering that trading volume in global currency markets is over five trillion dollars a day, these fines for behavior that allegedly went on for years are a mere slap on the wrist, hardly likely to deter future market manipulation schemes. However, I do expect financial interests to invest in better email encryption to make it harder for regulators to uncover “the smoking gun” in the future.

The kind of market manipulation that is easiest to discover is (like this case and the similar scheme three years ago that involved banks setting the LIBOR interest rate) the kind that creates regular patterns in publicly available data. Regulators will eventually discover regular anomalies and try to probe deeper to prove the illegal intent behind them. Almost impossible to prove are episodic or irregular market manipulations that are illegal, but often quite profitable, for any institution or large investor with the power to move any price. The widespread use of financial derivatives has made it much easier to profit from manipulation by betting a price will move a certain way and then moving it to cash in on your prediction.

The old kind of cartel was primarily interested in raising prices by agreement among producers, often enforced by their creditor banks. Cartel members jointly cut output and thus raised prices. This sort of cartel is still common, but the extreme financialization of the economy in recent decades has made another kind of cartel profitable. It does not matter if you raise or lower prices. It does not matter if you own or produce any of what you manipulate. Sometimes it is better if you do not. As long as you are confident of your power to move the price of something, you can bet first using derivatives, then take whatever action moves the price your way.

Modern finance theory is almost entirely based on the efficient market hypothesis (EMH), which argues that nobody has market power. Everybody is financial markets is supposedly a “price taker,” that is, they take prices as given by public markets but cannot buy or sell quantities of any asset sufficient to influence the price of that asset. This is radically false, except during the occasional interludes when nobody is trying.

First of all, any issuer of securities (stocks and bonds) is obviously big enough in relation to the market for its own stocks and bonds to influence the price of them. Issuing more (increasing supply) tends to lower the value of existing securities. Buying your outstanding securities back from the public tends to raise their price. Thus every issuer has market power over its own securities, at least. The only question is how often that power is used.

Of course, not only can issuers influence the price of their own securities, many other wealthy institutions and individuals can and do too. The biggest danger in manipulating prices is not that government regulators will catch you in the act. That is pretty rare and the penalties usually rather light. The biggest danger is that some other powerful private interests will detect your position and run against it in various ways. This potent though episodic private regulatory force within capitalism is what John Kenneth Galbraith called “countervailing power.” We will evoke this term often in future blogs.

The third news item that caught my attention last week is that New Jersey Governor Chris Christie, apparently eyeing a run for the presidency, is resisting calls to open his finances to closer public scrutiny because, like many politicians, most of his financial dealings are concealed within a “blind trust.”

The blind trust is an idea that became popular among American politicians in the aftermath of the Watergate scandal when the public appeared eager for campaign finance reform. The scheme is that upon taking office a politician’s stocks, bonds, and other financial holdings would be transferred into a special kind of account managed by a trustee, a financial professional. It is “blind” because the trustee reports to his client, the politician, only summary results of his accounts, not the details of what stocks or other assets he currently owns. The theory is that the politician is thus “blind” as to how actions he might take as a public official might affect the value of his own assets, and therefore less subject to corrupt influence.

In fact, a blind trust only blinds the public. As I know from talking to people in finance, anyone wanting to do a favor for a politician need only know who is his trustee. Then sweet deals can be passed along, shares of a juicy IPO, market manipulation scheme, etc. At some point, preferably on a golf course far from eavesdroppers, the politician need only be told “so-and-so is a friend of yours.” The trustee handles all the details, creating plausible deniability for the politician.

I prefer full disclosure to blind trusts. At least if you know what sorts of financial assets a politician’s trustee is investing in, then you have a chance of figuring out his secret friends and possible lines of influence.

I will save next week for an examination of the fourth issue that struck me in the recent news cycle: how a few hundred ISIS fighters can take over a major city. It is not entirely a financial issue, but there is some political economy at stake there too.

*****

*****

James H. Nolt is a senior fellow at World Policy Institute and an adjunct associate professor at New York University.

[Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons]