From the Fall 2015 Issue “Food Fight“

Click image to expand or download PDF

By Amy G. McDermott

To maintain normal bodily functions, an average adult needs between 1,200 and 2,000 calories per day. Our bodies have evolved to the point where we do not waste that precious energy, converting excess intake to muscle, or storing it as fat. Just as the human body has evolved to store food, cultural practices have evolved to preserve it. From Greenland to Syria, North Africa to the Arctic, fermentation, salting, smoking, and drying are traditional methods of preservation across cultures. Over millennia, peoples worldwide have survived by making food last.

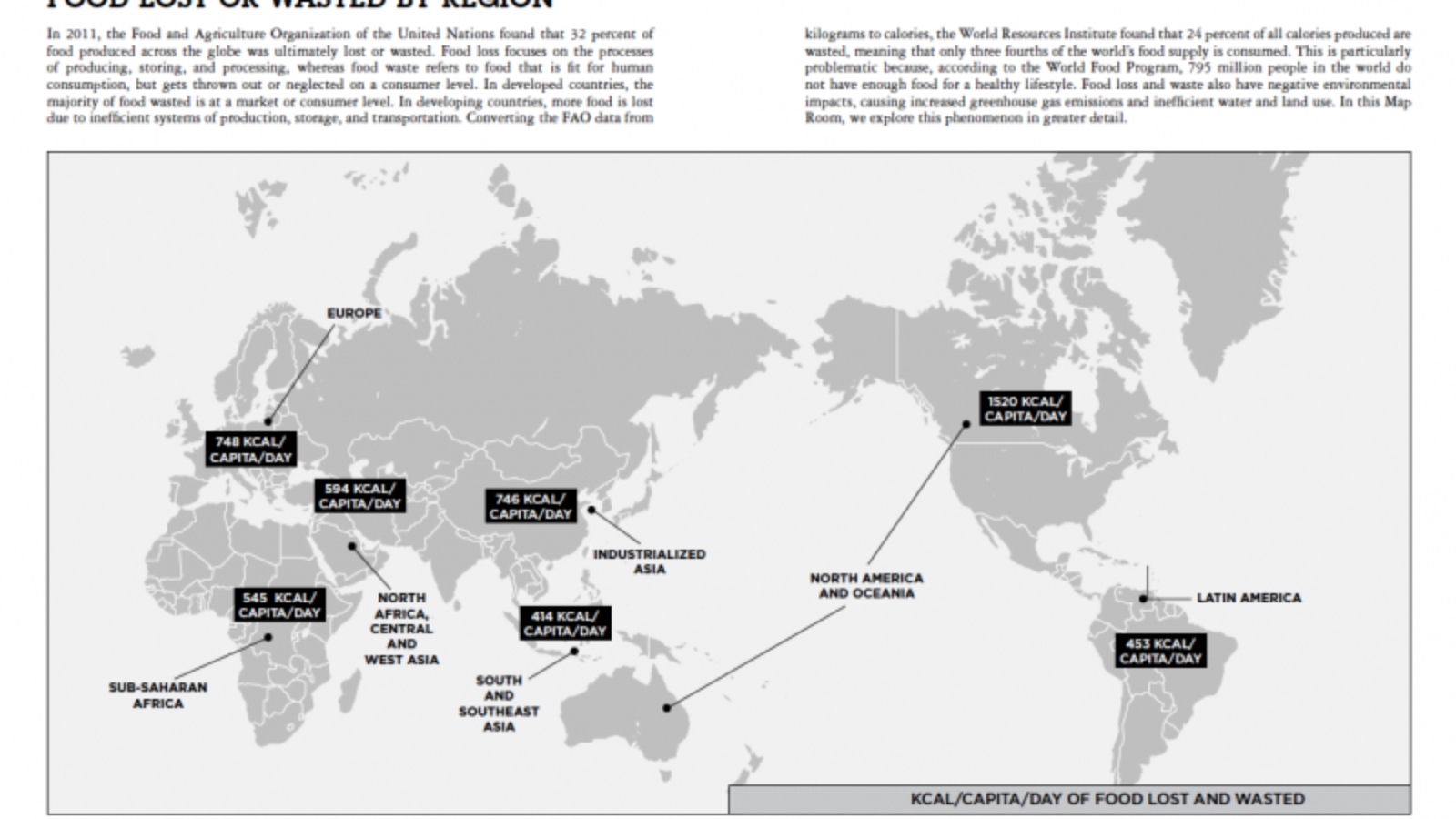

But today, an unprecedented amount of food is wasted. As traditional practices give way to increasingly homogeneous global diets, the cultural knowledge that carried our species through much of human history is being lost. A whopping third of the world’s food now goes uneaten—lost in harvesting, spoiled in storage and transport, unsold at market, or tossed out by consumers.

In developing nations, loss and waste are primarily caused by inefficient infrastructure—when farmers can’t access markets or storage facilities, few or poor roads slow transport, food processing is impractical, or access to refrigeration is limited. In developed nations, most waste happens at the consumer level—in supermarkets, restaurants, and home kitchens. Aesthetic standards for food and a high rate of product turnover contribute to supermarket waste. Misleading expiration dates, large portion sizes, and lack of public awareness generate waste in restaurants and homes.

A common thread unites these disparate causes of waste—underpinned by the spread of industrial agriculture and the supermarket revolution. As food systems modernize, large convenience stores replace traditional food markets, bringing affordable food to developing nations, and creating new access to consumers for farmers, but often driving smaller, traditional markets and producers out of business. As eating goes corporate worldwide, an unprecedented amount of food is lost in long production chains, or wasted by uninformed consumers.

SHOCKING COSTS

The costs of waste are shockingly high. Aside from monetary losses for farmers, producers, and consumers, waste also encompasses misuse of water, land, and fuel. The World Resources Institute estimates that an American family of four spends about $1,600 annually on food they will never eat. And nearly a quarter of the water used to grow those thirsty crops worldwide (almost 7 trillion cubic feet or about 528 billion gallons) is lost in our uneaten food every year. The energy used to grow and transport wasted food (over 3.3 billion tons in 2009) could power the entire United States for a year, and emits roughly the same amount of greenhouse gases.

Then there is the human cost. Worldwide, almost a billion people are food insecure, although we grow more than enough to feed them. Their hunger is the tragedy of limited access, inefficient infrastructure, and in many cases, failure to redistribute unsold and excess food. Eliminating waste is daunting, but the alternative is worse.

There are solutions. First, we get back to the basics—turn to the practices of our grandmothers and great-grandmothers, canning, salting, drying, pickling, fermenting, and otherwise extending the shelf life of our food. In Greenland, for example, the Inuit prepare kiviak—a meal of whole seabirds fermented in the body of a seal—for the long, harsh winters. Perhaps more appetizing to many of us, salted, smoked, and cured charcuterie has been a popular preserved food in southwestern Europe for at least 2,000 years and has now spread far more widely throughout Europe and America. In celebration of World Environment Day 2013, the United Nations Environmental Program and Food and Agricultural Organization highlighted traditional food preservation as one key way to reduce waste.

Anti-waste campaigns like Denmark’s Stop Wasting Food also target consumers. Comprised of over 30,000 Danes, Stop Wasting Food has been recognized by the United Nations for organizing school programs, informational videos and booklets, and community events in an educational campaign with reach across Europe. Similar initiatives have taken root in the United Kingdom, Portugal, Ethiopia, Zambia, South Africa, and the Asia-Pacific region.

LOST IN THE CHAIN

Food is lost at every step in the value chain, not only at the consumer level. To reduce losses between field and table—particularly in developing nations—farmers need roads to get their goods to market, and inexpensive, efficient means to store and transport crops. World Resources Institute recommends electric-powered refrigeration, evaporative coolers, resealable plastic storage bags, and small metal silos. So, by investing in infrastructure, governments can also invest in reducing waste.

These recommendations are critical to the livelihoods of farmers and processors worldwide, but they do not address the larger, underlying problems caused by industrialization. Supermarkets and megastores favor large producers, and require that more food be transported farther, to less-accessible markets than ever before. The availability of local markets—farm stands, farmers markets, food co-ops—is critical. Local access shortens the transport chain, gives farmers a place to sell perishables without long-term storage, and links consumers to smallholders, making them a more intimate part of the food chain.

For cultures of the past facing the vagaries of an unpredictable environment, wastefulness was often dangerous.It invited death. Modernization has largely enabled us to turn our backs on that mindset. We’ve created a decentralized waste machine, easy to overlook at the local scale, but devastating from a larger perspective. Starvation may seem impossible when there is a convenience store on every city block, but if we as a species ever forget how to stretch our food—particularly as our global population multiplies and lives longer than ever—the danger is very real.

Amy G. McDermott is a journalist covering ecology, conservation, and the humanistic side of science. She is the founding editor of Hawkmoth magazine, and has written for Natural History magazine and TED-Ed, among others.

*****

*****

Compiled by Brendan Krisel and Sasha Mitchell

Designed by Meehyun Nam-Thompson

Sources: World Resources Institute, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations