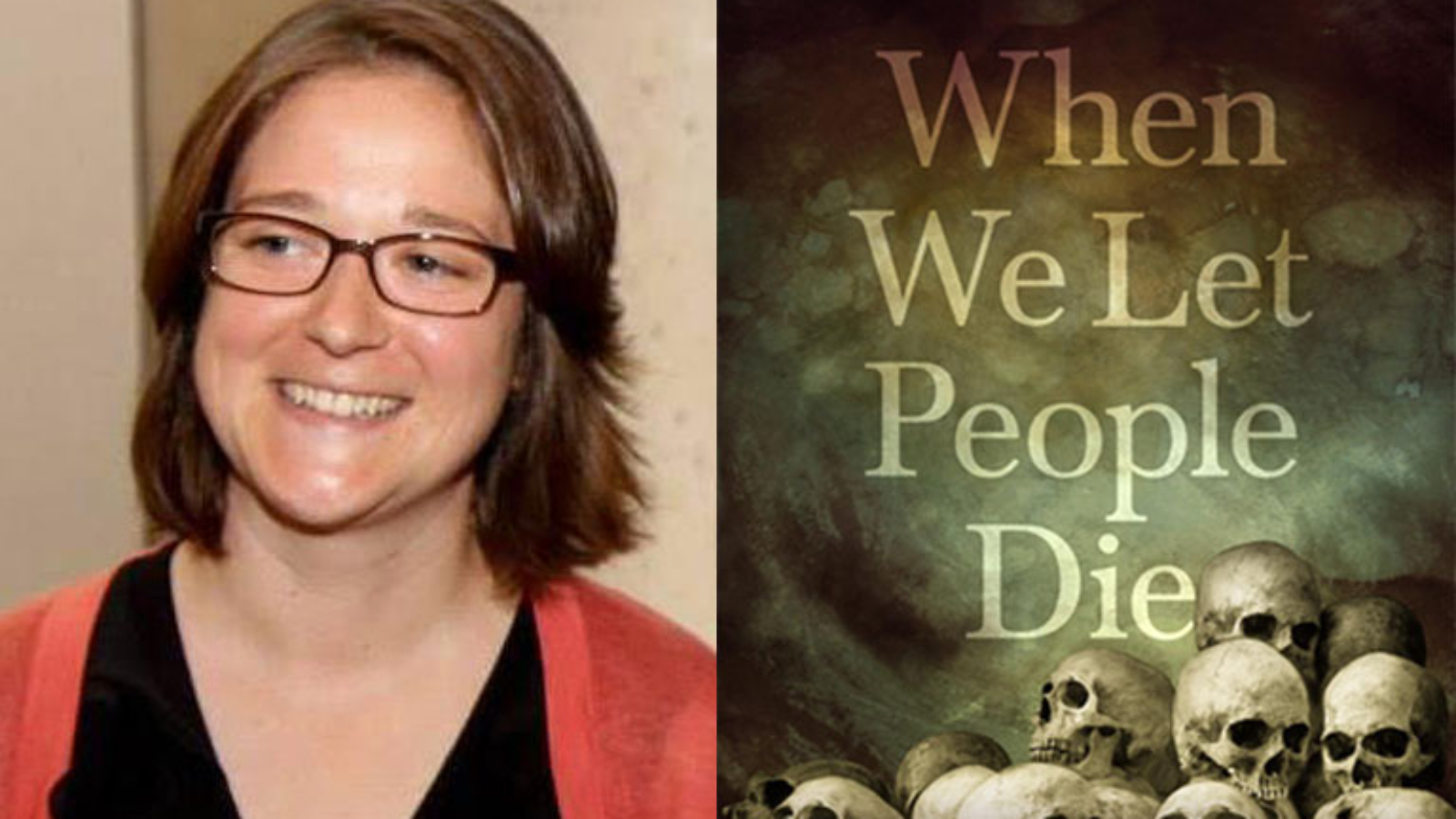

At the 2005 World Summit in New York City, every United Nations member state endorsed the “Responsibility to Protect” (R2P). While the principle is non-binding, by signing on the international community pledged to prevent and protect against human rights violations and crimes against humanity—a mandate it has not always upheld. World Policy Journal spoke with Corrie Hulse, managing editor of The Mantle and author of When We Let People Die: The Failure of the Responsibility to Protect, about the debate surrounding R2P.

WORLD POLICY JOURNAL: In your book, you write about the Responsibility to Protect, a commitment that came out of the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (ICISS) in 2001 and was endorsed by all the U.N. member states. Could you describe what the Responsibility to Protect is, and what it means for both sovereign states and the international community?

CORRIE HULSE: The Responsibility to Protect is a doctrine where the international community agreed that a state has the responsibility to protect its citizens from the four major crimes: genocide, ethnic cleansing, crimes against humanity, and war crimes. If a state is either unable or unwilling to protect its citizens from those crimes, then it becomes the responsibility of the international community to step in and protect those citizens. So the International Commission’s goal was ultimately for R2P to be focused on the prevention of these crimes. You hear a lot about atrocity prevention when you talk about R2P, although, as we see now, we often wait too long to act. And so R2P is mostly discussed in the context of response to crimes that are already happening.

WPJ: When the international community waits too long to get involved, what’s typically preventing them from doing so? Another way to put it: Why does the international community allow people to die?

CH: It’s a matter of political will and it’s case by case. If you look at what’s going on with the Rohingya right now, there was early warning that those atrocity crimes were bubbling up. Had states chosen to respond in, say, 2016 and been more forceful with with the current government in Myanmar, perhaps those crimes could have been prevented, and then you wouldn’t have seen this mass influx of refugees into Bangladesh. But there just wasn’t pressure on states to do that. It’s hard to see what could have been prevented until you look back, but in this case more pressure say, could have made prevention possible.

WPJ: The government of Myanmar seemingly hasn’t been willing to respond to the ongoing ethnic cleansing targeting the Rohingya. State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi has not even acknowledged it as ethnic cleansing and she’s been criticized for her inaction. Do we now see the international community scrambling to respond after the fact?

CH: Right. The U.S., for instance, is working on sanctions of military officials, and a lot of aid is going to Bangladesh in order to help people who are fleeing. There seems to be confusion about how to protect civilians and strengthen the government. Right now there’s a real struggle to figure out how countries should respond to that situation.

WPJ: Converse to what’s going on in Myanmar, what would you point to as a recent success of the Responsibility to Protect, either with a sovereign state or with the international community?

CH: I think there’s great movement within the NGO community. You may not see it from the outside, but these groups are building a broader acceptance of R2P within governments; finding allies within governments, which is really important; and generating more and more experts so that people understand what the doctrine is, how it can be used, and how each government can use it, unilaterally or within the United Nations. There’s a push recently to limit the veto granted to the five permanent members of the Security Council. The NGO community is increasingly pressuring governments to push for a suspension of that veto in atrocity cases.

WPJ: Since the Responsibility to Protect is non-binding, are NGOs one of the main ways through which private citizens could pressure their own government to intervene when a major human rights violation occurs?

CH: I wrote this book to reach the casual reader; it isn’t directed toward people who already know about R2P. With something like human rights and R2P, governments aren’t going to act unless their citizens want them to. And so as citizens get involved with their local NGOs and push for this action, soon you’ll see movement. Back in 2012, the huge Kony 2012 campaign saw a huge groundswell of support, with youth pushing for the U.S. to get involved in stopping Joseph Kony and the [Lord’s Resistance Army] in Uganda. And it did get the U.S. government to send military assistance, becoming more involved in the conflict than it had been before. That’s an example where, without citizen involvement, the government wouldn’t have taken action.

WPJ: With the viral YouTube video “Kony 2012” and again with coverage of the Rohingya, social media and the internet have played a big role in bringing people’s attention to mass atrocities. How does that affect the way the international community takes up the Responsibility to Protect?

CH: I don’t think it will necessarily affect the doctrine, per se. But it definitely will highlight the human rights issues. As these stories are told, people will see where their government needs to be involved. While Syria has been such an astronomical failure in terms of the international community’s response, we’ve seen how social media has allowed people around the world to understand what’s going on. I followed Bana al-Abed, the 7-year-old girl who was live-tweeting from Syria. She escaped and is now living in Turkey. Following her story in real time as her city was getting bombed, or reading the social media feeds of teenagers in Ghouta live-tweeting the bombings there, people will, I think, reach out to their governments and say, “Are you seeing what I’m seeing on social media here?”

WPJ: Shifting a bit toward U.S. policy, President Donald Trump came into office last January promoting this idea of “America First.” How does that ideology affect the United States’ relationship with the Responsibility to Protect?

CH: I think R2P’s on the back shelf. I don’t think he’s necessarily changed anything because I’m not sure he knows anything about it. But as we see the State Department downsizing, and cutting text about human rights and women’s rights, I definitely don’t see R2P being a priority in this administration. And as it becomes less of a priority, the U.S. could become less of a leader in anything that concerns atrocity prevention.

WPJ: If the United States is putting the Responsibility to Protect on the back shelf, does that affect how the rest of the world responds to humanitarian crises?

CH: We’re not the only country doing this, so if we’re not there, it’s not as if it stops. But our leadership is powerful in atrocity prevention, especially when it comes to Security Council votes. The upside is, while [U.S. Ambassador to the U.N.] Nikki Haley is problematic in a lot of areas, she has voted for things like resolutions on Syria. I don’t know whether she and Trump agree on those matters, but she has been voting in favor while Russia has been vetoing. Still, the U.S. is definitely not the leader it used to be, and it will be interesting to see what the long-term effect is, whether just a pause for a few years or something that will take us a decade or more to come back from.

WPJ: For anyone who reads your book and isn’t very familiar with R2P and the issues surrounding it, what’s the key thing you hope they take away?

CH: I would encourage them to ask questions. My goal was to take things that often are fairly jargon-filled and make them less daunting for someone who’s interested in human rights but didn’t study international law. It’s important that we all educate ourselves on these topics—that we really dig in and ask questions and keep reading. It’s important for us to know what’s going on with the Rohingya and what’s going on in Syria. It’s important for us to be global citizens.

* * *

* * *

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

[Interview conducted by John Kiehl]

[Photo courtesy of Corrie Hulse]