As economic opportunities fail to materialize and unemployment spreads across Western Europe, prospective immigrants decide it's a bad time to move while the recently arrived are return home. All the while, further barriers to immigration are erected to protect the jobs of domestic-born workers. In the final installment of a three-part series (parts one and two), the World Policy Journal explores the long-term implications of the post-recession immigration slowdown, reported in the OECD’s annual International Migration Outlook.

***

Immigrants have been particularly hard-hit by the recession in Europe. Cutbacks in spending on consumer goods and housing have caused a steep fall in demand for labor in developed countries, particularly the kinds of cheaper labor provided by immigrants working in factories, construction and services. Immigrants in lower-skill fields, especially young ones, are the first to lose their jobs.

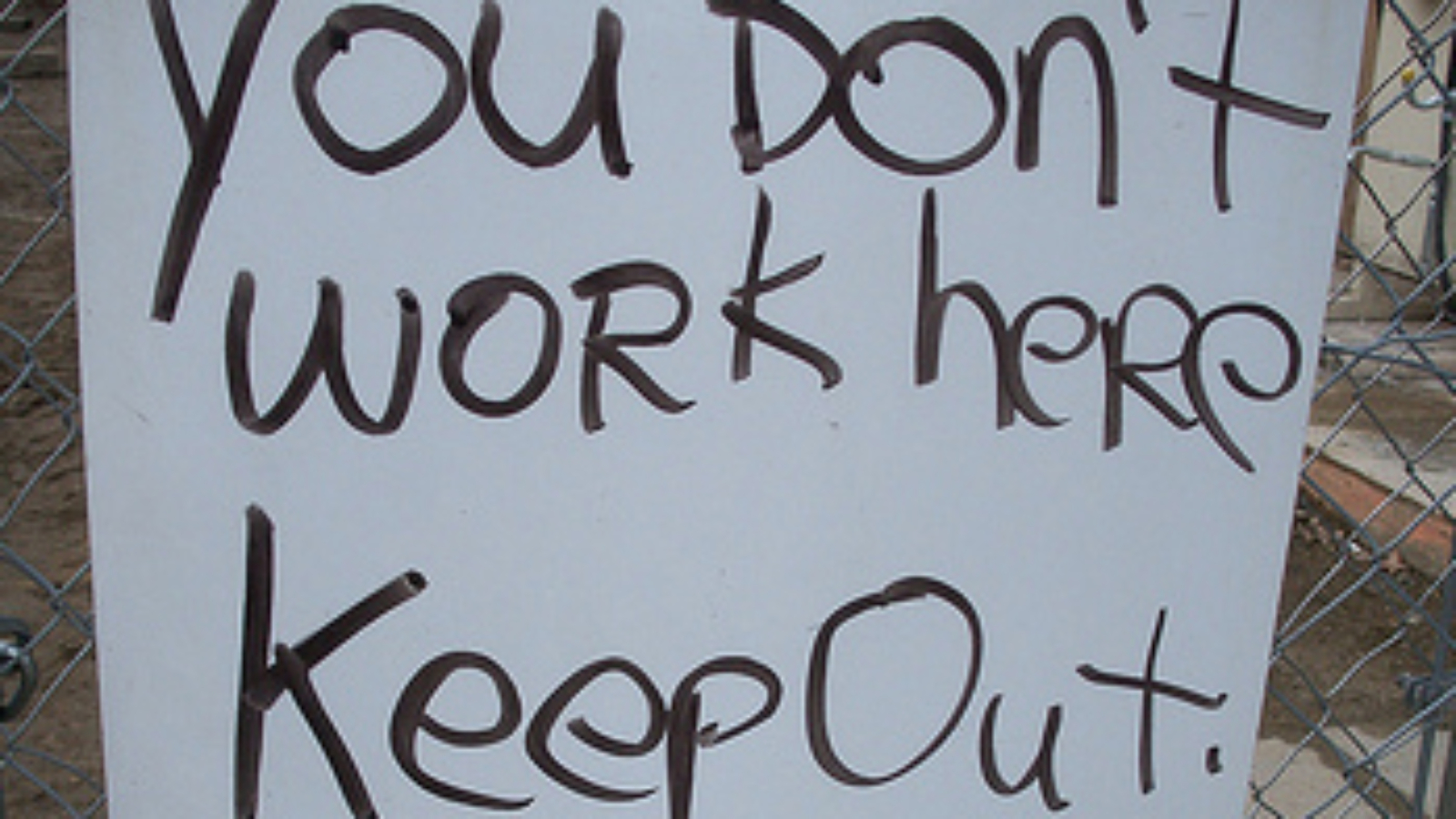

Domestic-born public employees vote to protect their jobs, while the foreign-born have neither the numbers nor clout to affectively sway politicians. It is more politically palatable for European politicians to send home temporary workers and limit immigration than to let the market shed the least productive labor.

“Yet, migration did not come to a halt,” the OECD reminded, “in part because family and humanitarian movements are less sensitive to changes in labor market conditions, but also because of structural needs and demographic trends.”

But the decreasing immigration trend line will need to be reversed, the organization warned, if the labor needs of an aging population in the developed world are to be met.

Europe’s ‘Bermuda Triangle’: Debt, Decelerating Growth, and Demographic Decline

Europe’s biggest structural problems are due largely to improper—or at least unsustainable—allocations of public spending (Europe’s debt levels were covered in part one). “Governments have spent years padding civil-service payrolls,” the Economist complained two weeks ago, “unveiling benefits like baby bonuses or early-retirement payments just before elections, and shoveling subsidies to politically powerful interest groups.”

These spending policies have played a large role in Europe’s current debt crisis, and many blame them for the slow growth forecast across Western Europe in the decade ahead.

Without an increase in current migration rates, the working-age population in OECD countries will come a virtual standstill in just a decade, increasing by only 1.9 percent, compared with an 8.6 percent increase between 2000 and 2010. The UN Population Division projects the working-age population of the European Union to shrink by 20 million between 2005 and 2020—and for 40 million more to be counted among those over the age of 65. (See graph, from The Economist)

Take the example of Francois Couder, a 43 year-old worker (interviewed in a related story on NPR) who lays underground cable for France Telecom. He complains that the rules have changed since the company was privatized in 1998. “We came into the company with a clear contract to work 40 years and retire. Now, the closer we get to retirement, they say, no, you need to go a little longer. Will they keep adding years? … [If so,] what’s the point?”

Couder’s assumption that terms can remain constant on a 40-year contract is emblematic of the European mindset and its massive self-contradictions. It is clearly impossible to preserve public benefits like low retirement ages with generous pensions for low-skilled workers while allowing immigrants, from places like Eastern Europe and North Africa—who will do the same work for lower wages and work for longer—to reach ten, 15, 20 percent of the population. The situation becomes more untenable if they follow the European example: retire at 60, file for a pension, and put the continent further into debt.

The immigration slowdown accentuates the most fundamental shift in the global economy since colonization. As the developing world’s population grows and becomes more productive—while Europe ages—the gap in economic opportunities between the two worlds narrows and the distinction between them means less. As Western Europe sheds jobs and becomes restrictive to newcomers, prospects are improving in immigrants' home countries. That immigration inflows to Europe's OECD member countries have dropped hugely is unsurprising. What would surprise is if Europe were to do little about it.

–David Black