By Belinda Cooper

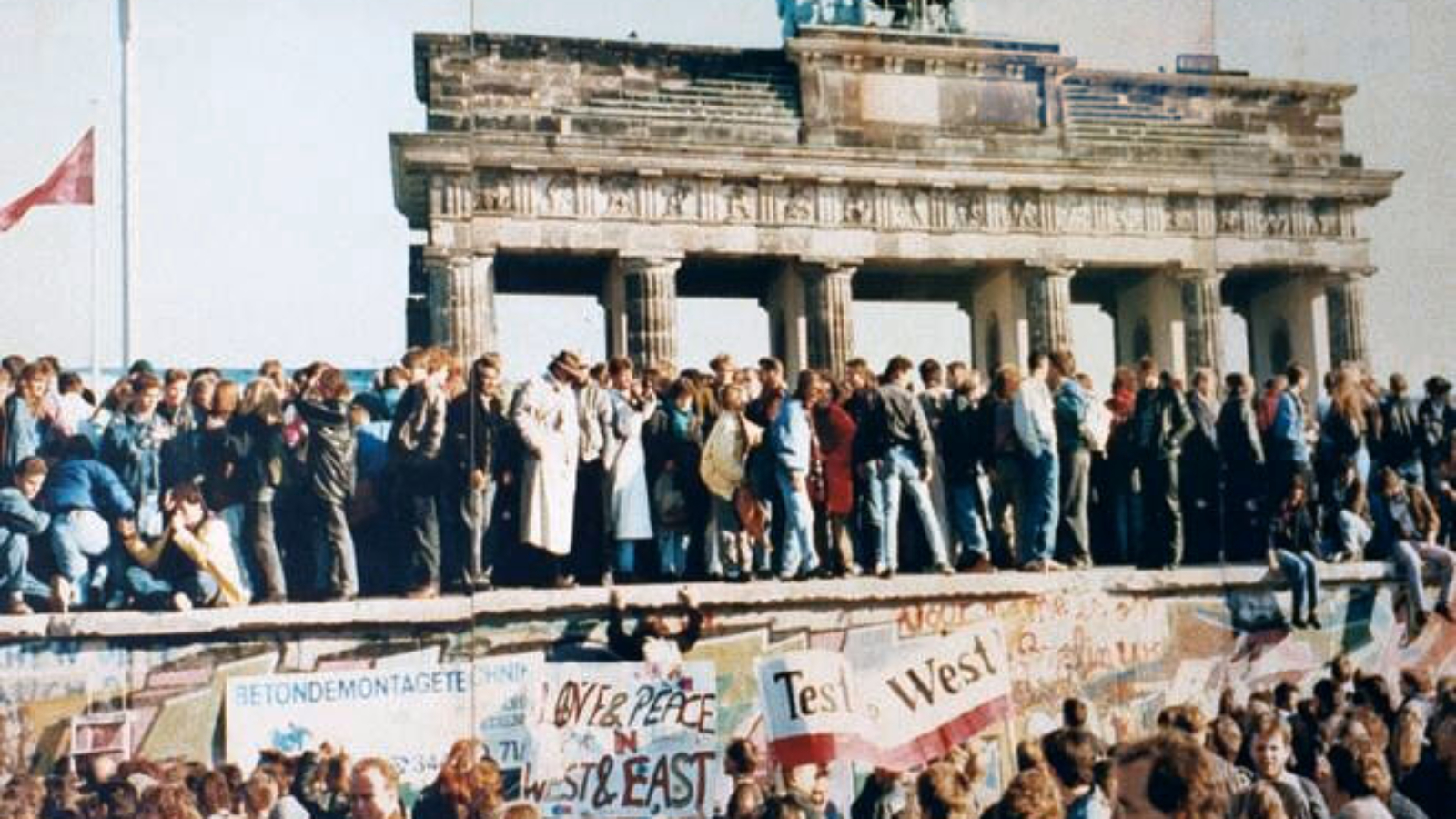

In the heady days of autumn 1989, I lived in West Berlin, working closely with an East German dissident group and traveling around Eastern Europe as a journalist and fixer for Western media. I was privileged to have a front-row seat as East Germans rose up peacefully, the Wall fell, and people all over the region demanded their freedom. Even though the Egyptian context is different in many ways, the events unfolding there in recent weeks have had a joyful, if sometimes anxious, familiarity. Yet my observations in Germany two decades ago also bring some sobering thoughts amidst the rejoicing.

This moment is certainly an incredible one: I recognize the unforgettable euphoria and sense of limitless possibility after throwing off decades of dictatorship, and the unity of purpose bringing together the most disparate people and groups. Yet this high cannot last. Different interests and visions of the future will assert themselves. This leads, on the one hand, to the wonderful spectacle of a long-silenced people debating and arguing in the streets–a development that’s already been noted in Egypt and a precursor to the messiness of democracy. But it will also bring a sense of letdown as unity breaks down and the parameters of reality and legality become clear. It’s a psychological moment that has to be taken seriously, because the failure to rapidly achieve all their hoped-for goals may sour people on the idea of democracy. Yet because dissidents all worked together toward the overthrow of the dictatorship, even when they disagree and separate into distinct parties and interest groups, that shared experience and the friendships forged in adversity are likely to give them a common level of communication that makes dialogue possible.

Still, participating in a democratic system is not something learned overnight. Revolutions like the East German, Eastern European, and now Egyptian ones prove that the desire for freedom and participation is deeply rooted, but that doesn’t mean the democratic mechanisms of debate, compromise, majority rule and minority protection have been internalized. Perhaps unfortunately, Egypt does not seem to have anything like the Round Tables set up to act as interim governments throughout Eastern Europe once the regimes began to totter and fall. In Egypt the military has taken on that role. Those Round Tables allowed new opposition parties and civil society groups to work toward reform with what remained of the old governments, and gave them an opportunity for hands-on experience of leadership before new elections and full transfers of power. In any case, while the Egyptian protesters have given much cause for hope, the establishment and internalization of new institutions and modes of participating will not be simple.

Finally, any democratic Egyptian government will face the problems of “transitional justice” – how a society emerging from dictatorship and repression deals with collaborators with the previous regime. Should former government bureaucrats, teachers, or police officers be kept from working in the new system, as in Czechoslovakia’s system of lustration? Should members of the former regime be put on trial? Should secret police files be made public, as they were in Germany? What about a truth commission, as in South Africa and many other transitioning societies? Some will call for amnesties, but new governments must weigh the temporary social peace that these may bring against the importance of establishing the principles of rule of law and accountability.

All these methods have their strengths and weaknesses. The new government must satisfy the popular desire for truth and justice without falling into vengeance, depriving society of the experience of the old elites, or (as with Iraq’s Baathists) creating a large group of disaffected people with little to do but make trouble. This process, too, will not please everyone. Some will feel it does not go far enough; an East German dissident famously complained, “We hoped for justice, and got rule of law.” Others will argue that moving forward is more important than dealing with the past. Yet societies that have tried to avoid a reckoning with the past have found that, sooner or later, it comes back to haunt them. Fortunately, Egyptians have the experiences of societies from Latin America to Europe to Africa to inform them as they strive to create a transitional process that works for them.

Belinda Cooper, a Senior Fellow at the World Policy Institute, lived in Berlin in 1989 and closely followed the revolutions in East Germany and Eastern Europe.