Confessions of a Secular Missionary

By William Powers

Consider this radical notion: the environmental crisis is not all about gloom and doom. Instead, it is a door that opens up to a renewed vision of how we live and find happiness. It starts with a conversation about the question, “How much is enough?”

This conversation is vitally important because of some bad news. Technology alone won’t save us from environmental collapse. It will take four to five generations of technological innovation to achieve carbon-free production. Alas, we don’t have that much time. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says the atmosphere’s tipping point could come within the next few decades. If climate change is not reversed swiftly, its effects could prove irreversible.

The human population will hit seven billion within the next year. From remote Umbrian villages to the sprawling cities that house China’s growing middle class, many of the world’s inhabitants dream of more. But the road to more leads only to collapse. If everyone in the world consumed the way an average American consumes, we would require an additional five planets’ worth of resources. More than an ethical imperative, the need to reduce our material expectations and consumption is essential for the very survival of our species.

The good news, however, is that consuming sustainably doesn’t have to hurt. I’ve spent a good part of the last 15 years as an aid worker and analyst, traveling to some 50 countries and examining how human civilization can get back into harmony with our biosphere, by aligning our consumption with our real needs. What I’ve found has left me surprisingly optimistic.

THE GOSPEL OF MORE-IS-BETTER

Perhaps you’ve heard the story of the indigenous man whistling his way through the jungle around his village when he comes upon a well-dressed aid official with a clipboard in hand.

“What are you doing?” the official asks.

“Walking in the forest,” the man replies.

“You should be working,” the official says, suggesting the man and his fellow villagers cut down the forest and build a profitable cattle ranch. When the indigenous man asks him why, the official says, “To earn money.”

“Why do I need money?” the man asks.

“So that you can have assets and savings.”

“Why do I need to have those things?”

Exasperated, the official blurts out, “So that someday you can retire and stroll happily through the forest!”

“But that’s what I’m doing right now,” the man says, continuing on his way.

For a long time, I was that aid official. That was my clipboard.

I spent years as a secular missionary, preaching the gospel of more-is-better. Like missionaries of all stripes, my deeds sometimes failed to match my words. As a fellow at the World Bank, I flew business class to a sustainability conference in India. As an aid worker in war-ravaged Liberia, I lived in a handsome villa on the coast. In Bolivia, my fellow development experts and I admired one another’s luxury apartments while the Illimani glacier melted above us—a victim of the global warming caused in part by our own appallingly large carbon footprints.

In short, I’ve been a poster child for the slogan: GOT FOUR MORE PLANETS?

How could it be otherwise? Consumption is bound up in America’s cultural DNA. One of my earliest memories is of July 4, 1976. I was five years old. My parents took my sister and me from our long Island home into Manhattan to see the fireworks extravaganza celebrating the American bicentennial. I can still see the color and feel the firepower that rose from the dozens of barges in the Hudson and East Rivers, our collective national pride blooming so colorfully in the sky.

Eating hot dogs in fluffy white buns, drinking Coke, and watching fireworks, I knew my country was great. I’d help my dad hang the Stars and Stripes in front of our comfortable suburban home, then watch him get the grill going. He expertly flipped the burgers and rolled the hot dogs. The salt on my skin after a day at the beach, the taste of mustard—all of it gave me a hopeful feeling. It felt like freedom. It promised something.

These were the rituals that gave life to the mythology of my American child- hood. Summer drives across the country, a big house with a back yard, my parents’ stable incomes—all confirming the myth and converting it into our reality.

We epitomized the American Dream. But over the years, it became apparent to me that the dream could end—or that the dream was less attainable for others. What seemed to be unlimited economic growth took on darker shades.

As I grew up, Long Island was being paved over. A few small farms and patches of wild forests had survived suburbanization, but most had disappeared forever, transformed into a million uninspired cul-de-sacs. Beyond the safety and prosperity of my upper-middle-class life was something I couldn’t yet articulate—ecocide, the destruction of our planet by our current economic model. Until then, it had invisibly fueled our lifestyle. Now, the effects were surfacing, as Nobel Laureates began predicting that global warming could cause half the planet’s plant and animal species to become extinct in just a few decades.

The price of my privileged upbringing was my ignorance of the true effects of global hyper-development, which degrades and poisons the human being while it destroys our planet. I was taught to see myself as a child of the American Dream. In reality, I am a child of the Age of Ecocide.

THE 12×12 SOLUTION

Four years ago, I spent 40 days living the minimalist life in a 12-foot-by-12- foot cabin in the north Carolina woods. I chronicled this existence in my book, Twelve by Twelve: A One-Room Cabin Off the Grid & Beyond the American Dream. I’ve spent much of the past year traveling the United States, asking thousands of people, millions if you count TV and radio, “How much is enough?” Whenever I talked directly about ecocide and global warming, dystopia and extinction, eyes glazed over—a natural human defense, a denial mechanism that builds a wall between me and the audience. But if you want to change attitudes about consumption it won’t ever happen through shame or blame. The revolution must be irresistible. What audiences everywhere did love is the concept that Less is More. (Never mind that Less is Moral. How dreary.) Guide folks into a vision of their lives with less material clutter and over-scheduling and you strike a powerful chord.

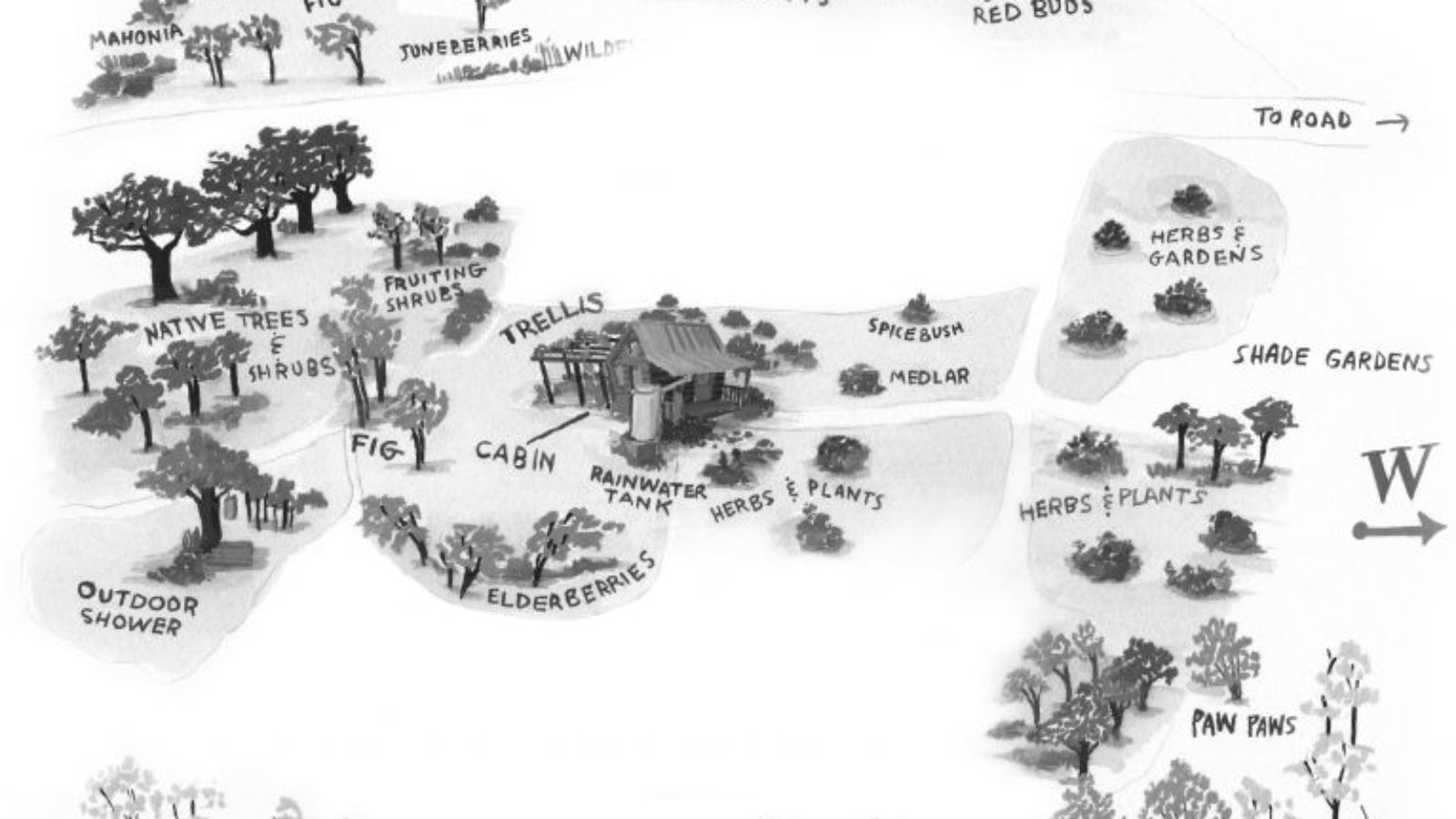

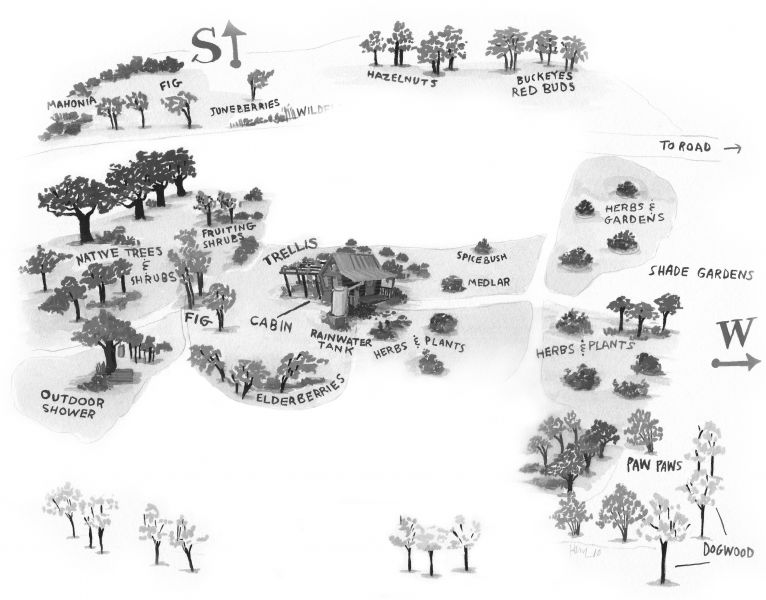

I came to the cabin in the woods by way of a 60-year-old American physician, a woman I refer to in Twelve by Twelve as Jackie Benton—a pseudonym, to protect her privacy. Eight years ago, Benton downsized to a tiny off-the-grid cabin in North Carolina. The first time I met her, she was tending to a stray honey bee in front of her 144-square-foot home, with no electricity or running water. She introduced me to the world of her “wildcrafter” neighbors—organic farmers, biofuel brewers, eco-developers, and homeschoolers. As a senior physician, she could earn a quarter of a million dollars a year. Instead, she limits her income to $11,000 a year—just enough to satisfy her basic needs—and lets the health care system keep the rest. To my surprise, she invited me to stay, alone, in her 12×12. While Benton traveled, I spent a season there, exploring what the poet Wendell Berry called “the strenuous outline of enough.” I was amazed by how easily I adjusted to candlelight instead of electric lights, food out of Benton’s lush gardens instead of a supermarket aisle. I found an immense amount of pleasure in simplifying, and have carried the practice into my life beyond the cabin.

The 12×12 forced me to consider “enough”—the sweet spot between too little and too much. Not everyone will live a complete 12×12 life, as Jackie does. But all of us can ask, “What’s my 12×12?”

I live in New York City now. So part of my 12×12 is taking public transport—I don’t own a car because it’s not needed here—and growing some of my food in a city garden.

WHO’S IMPOVERISHED, ANYWAY?

In October 2011, I visited the University of Minnesota’s Humphrey Institute of International Affairs to give a talk en- titled “What’s Your 12×12?” In the audience were professionals and intellectuals from more than a dozen developing countries. I was expecting a wholesale rejection of the “voluntary simplicity” concept. After all, these were all successful developing-country elites who were benefiting from rapid economic growth and increasing prosperity.

But the overwhelming consensus in the room was that reducing consumption is more than a survival imperative. It is actually a more desirable way to live. One audience member, a thirty-something man from China, described the contentedness of his childhood, growing up in a 10-foot-by-15-foot house—the solidarity it brought, the freedom from clutter and distraction. Others spoke of the need to ratchet up living standards, but only to a point that would allow for an intelligent, holistic balance between doing and being—just enough, and not more, food, shelter, fresh air, family and friendship.

At a certain point in my “development” career, I began to question the whole notion of impoverishment. Indeed, most of the so-called “impoverished beneficiaries” of my programs seemed better off than me. They wore bigger smiles. They engaged more easily in the moment. Through their kinship networks and close relationship with the land, they achieved a greater sense of meaning and purpose. I talked with these folks everywhere from the Gambian coast to the Amazon, and the vast majority told me they would not trade their lifestyle—with its simplicity and rootedness—for mine, despite the obvious difference in wealth and mobility.

I do not mean to glorify material destitution. I’ve spent many hours with some of the millions of people for whom a 12×12 would represent an unattainable level of prosperity—luxury, even. They live zero-by-zero, with no lush organic gardens, no gently flowing creek, no shelter at all. They live in what you might call the Fourth World—those anarchic, failed places where community and basic necessities have been decimated by war, famine, and natural disaster. So, when discussing relatively “poorer” countries, I always make a clear, explicit distinction between people living in a state of material destitution and people living healthy subsistence lifestyles.

There’s a point where one’s material life is in balance—possessing neither too much nor too little. Roughly one- fifth of humanity has too much and is overdeveloped; another fifth or so has too little, and is underdeveloped. Neither of these groups experiences general well-being. The former can rarely experience the simple joy of being. The latter are so destitute that they can’t sustain their bodies physically. Fortunately, the third group—those with enough—is by far the largest. It is what I redefine as “sustainably developed,” ranging from subsistence livelihoods like the Mayans of Guatemala to the economic level of the average Western European in 1990. By this rough calculation, 60 percent of the world lives sustainably. In other words, if everyone lived as they did, our one planet would suffice to feed, clothe, shelter, and absorb the waste of everyone.

MOVING FORWARD

None of this is to say that downsizing from “too much” to “enough” will be easy. Modern societies inculcate the very self- interested, materialistic values that lead directly to ecological destruction. Policies and programs must be formulated to promote values known to support ecologically sustainable attitudes and behavior, including balanced consumption.

One place to start is to restrict the most overt promotion of consumption, otherwise known as advertising. Environmental psychologist Tim Kasser calls commercial advertising “the best funded, most sophisticated propaganda campaign ever employed in human history, with millions of dollars spent yearly to pay researchers to investigate how to ‘press the buy button’ and billions of dollars more spent to pay for-profit media corporations to deliver these messages to children, adolescents, and adults.” Advertising messages that inculcate the belief that people’s worth is dependent on what they own now appear in almost every possible venue. A global ban on all forms of marketing to children under the age of 12 might sap the global marketing juggernaut of some of its strength. It would halt the practice of preying on young people whose cognitive abilities and identities are still forming, making them particularly susceptible to advertising. This may seem like an extreme idea. After all, such a ban would conflict with the liberal-democratic value of freedom of expression. But moving toward genuine sustainability will inevitably involve trade-offs, and this is one that I would be comfortable making.

As a wise friend from an indigenous community in the Amazon once told me, “We have the power to imagine something new…a world of ‘enough’ that is marked by happiness and sustainability.” one place to start, on a personal level, is to question the myth that having more is being more—that we need to consume our way out of recession, that failing to work 70-hour weeks means we’ll revert to Homo erectus.

Another way to become part of the solution is to get directly involved. During the past decade, hundreds of thousands of grassroots NGOs and community groups around the world have formed with the specific goal of challenging over-consumption. The sustainable consumption movement has gone a long way toward producing a major paradigm shift. And like other social movements, it begins with a vital, urgent question, one that will mark the early 21st century, and one I continue to ask myself every day. How much is enough?

*****

*****

William Powers is a senior fellow at the World Policy Institute. He has worked for more than a decade in development aid and conservation in Latin America, Africa, and Washington. His most recent book is Twelve by Twelve: A One-Room Cabin Off the Grid & Beyond the American Dream (New World Library, 2010).

[Illustration: Hannah Morris]