As the global gap between the haves and the have-not grows ever wider, attention focuses on the top and the bottom of the socioeconomic spectrum. But what about the middle? Creating sustainable development might ultimately hinge on how we understand “middle class,” since achieving that vaguely defined status is now the ambition of billions of people. To find out what it means to be middle class, World Policy Journal chose to explore three countries at different levels of economic development—Liberia, with a per capita annual income of roughly $400; Indonesia, at around $4,000; and the Netherlands, at around $40,000. We asked writers in each country to profile its middle class—its aspirations, politics, and prospects.

*****

*****

LIBERIA: VERY RICH, OR VERY POOR

By Tecee Boley

MONROVIA—It is after 8 o’clock in the evening on the Barnersville estate, a low-income housing project on the outskirts of the capital of Liberia. The entire area is dark. A few candles illuminate small shops along the road. A path leads to Kollie Yard, a cluster of faded whitewashed houses surrounding a sand pit. The homes are modest; more than a hundred people share a common toilet. Saye Guinkpa has just returned home from central Monrovia, where he earns $250 a month working as a trainee at the Ministry of Justice. In a white T-shirt and khakis, the 30-year-old emerges from the two-room unit he shares with his girlfriend and two roommates. On the floor is a full-size mattress draped in a mosquito net. There is no electricity or running water. Guinkpa pays $15 a month for the privilege of living here.

With a degree in economics and accounting from the University of Liberia, Guinkpa earns more than four times what a policeman or entry-level civil servant can earn, and much more than the dollar a day that three out of four Liberians live on. Guinkpa says he was shocked to learn just how poor Liberia is compared to the rest of the world—a reality he only became aware of when he reached college. “It’s why I decided to press on with economics,” he says.

In Liberia, income disparities are so wide that, in a sense, there are only two classes—very rich and very poor, with a gaping hole in the middle. A recent report by the African Development Bank Group estimated that only 4.8 percent of Liberia’s population can be considered middle class—the lowest percentage on the continent, among the countries for which such data is available. Only 15 percent of the workforce is formally employed, and 79 percent of those who are employed nevertheless do not enjoy a steady income, according to a recent Ministry of Labor survey. In this bifurcated socioeconomic landscape, people like Guinkpa are the closest thing there is to an emerging middle class—educated and employed, but hardly members of the elite.

While he enjoys his job and realizes he is fortunate, Guinkpa’s lifestyle does not match Western notions of middle-class comfort. He doesn’t have a television or a car. He wakes up at 5 o’clock in the morning to bathe outdoors with a bucket, in the privacy afforded by darkness. He spends half his income on shared taxis that take him to work downtown. A vacation is out of the question. His $3,000 annual salary may seem generous, considering that the annual average income per capita is $400. But in Monrovia, where an influx of foreign aid workers has resulted in double- digit inflation, the cost of living is high. Even the most humble roadside restaurant charges the equivalent of three dollars for a plate of food. “There’s no room for saving,” Guinkpa says. “It would mean I would have to starve.”

Guinkpa aspires to become a financial analyst for the government, earning twice what he now takes home. He fears that, instead, he will have to work a lower-paying job his entire life. He believes that the fact that he was educated in Liberia—and not abroad, like some children of the elite—ill keep him from any kind of real upward mobility. “Someone who graduated abroad has vast experience, he has learning with technology that’s far ahead of you,” he says. “When he comes back and you and he go for a job in a competitive market, he will win.”

THE COSTS OF CIVIL WAR

Following 14 years of civil war that ended in 2003, the country has had to rebuild state institutions from the ground up, repair a shattered national infrastructure, and above all help individual citizens contribute to economic growth and the rebuilding of the state. The war was a stark example of how class inequality can stir unrest. The country’s traditional elites are the “Americo-Liberians,” descendants of the freed American slaves who founded the country in 1822 and, ever since, have oppressed the descendents of the indigenous people their ancestors encountered upon arrival. In 1980, the indigenous-descent population rose up and overthrew the Americo-Liberians. Reeling from widespread corruption and economic mismanagement, the country remained highly unstable, as factions within the new power structure fought for control. Liberia finally erupted into full-scale war in 1989, when Charles Taylor, a former Liberian government minister who had fled the country and was living in Cote d’Ivoire, invaded with the backing of Libyan President Muammar Gaddafi.

The elite, including most skilled and educated workers, fled the country, and the economy collapsed. According to government figures, GDP fell 90 percent between 1987 and 1995, one of the sharpest economic collapses ever recorded in any nation. By the time of the first postwar elections in 2005, average income in Liberia was just one-quarter of what it had been in 1987, and just one-sixth of its level in 1979. By 1993, agricultural production—historically the most significant contributor to GDP—had dropped by 75 percent from its 1979 level, as people fled their farms.

Still, peace has paid some dividends. By 2008, agriculture had returned to 61 percent of GDP, according to the World Bank. And the economy is unquestionably expanding, with annual GDP growth averaging 9 percent since 2004.

MIDDLE CLASS, OR WORKING POOR?

Chid Liberty owns a garment factory in Monrovia that employs 40 people, mostly women. He plans to scale up production over the next 18 months and eventually employ 900 people. Most of his workers earn $100 a month, plus a $30 transportation stipend and a bag of rice. The company also provides healthcare and a 100 percent annual savings matching program. Liberty’s father was Liberia’s ambassador to Germany during the regime of Samuel Doe, the Liberian soldier who overthrew Americo-Liberian rule in 1980. Liberty’s family later fled the country and went into exile in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Liberty is now one of the growing number of Liberian exiles returning to help rebuild the country.

“If anyone says, ‘Yes, there is a middle class in Liberia,’ I believe they have the middle class confused with the working poor,” he says, sitting at the restaurant of one of Monrovia’s few high-end hotels. “I don’t think a security guard earning $60 a month can be called middle class, when one bag of rice could cost him $40. There’s no way to support a family there.” While Liberty would like to pay his own employees more, he sees Liberia’s low wages as a competitive advantage that he must exploit.

Liberty believes cultivating a middle class will require investments in small and mid-size businesses like his, which might allow him to become profitable enough to raise salaries. “As we move forward with larger corporations coming in now—which I’m in favor of, because they do provide some level of employment—they’re not going to have jobs for a lot of Liberia’s working poor,” he says. “And I really think it takes a concerted effort on behalf of Liberian entrepreneurs and our policymakers to figure out what types of industries we can bring in that specifically target jobs for the poor. I’m not sure that oil companies or many of the major concessionaires are going to do that.”

BRIDGING THE GAP

To bridge the gap between the poor and the rich—to help build a genuine middle class of families that have managed to bootstrap themselves out of poverty—Africa’s first female president, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, introduced the Poverty Reduction Strategy (PRS) in 2008. The three-year, multi-pillared plan stresses the creation of a middle class through the attraction of foreign investment, which Johnson Sirleaf believes is critical to the growth of the economy. It also aims to empower domestic entrepreneurs to conduct business and create jobs by expanding microcredit and investing in infrastructure, increasing the size and purchasing power of the Liberian middle class. More than 200,000 new jobs have been created since Johnson Sirleaf took office in 2006, according to the government. At the same time, the Central Bank has injected $5 million into the domestic economy under a credit stimulus initiative for small and mid-size commercial borrowers, which also involved reducing interest rates from 14 percent to 8 percent.

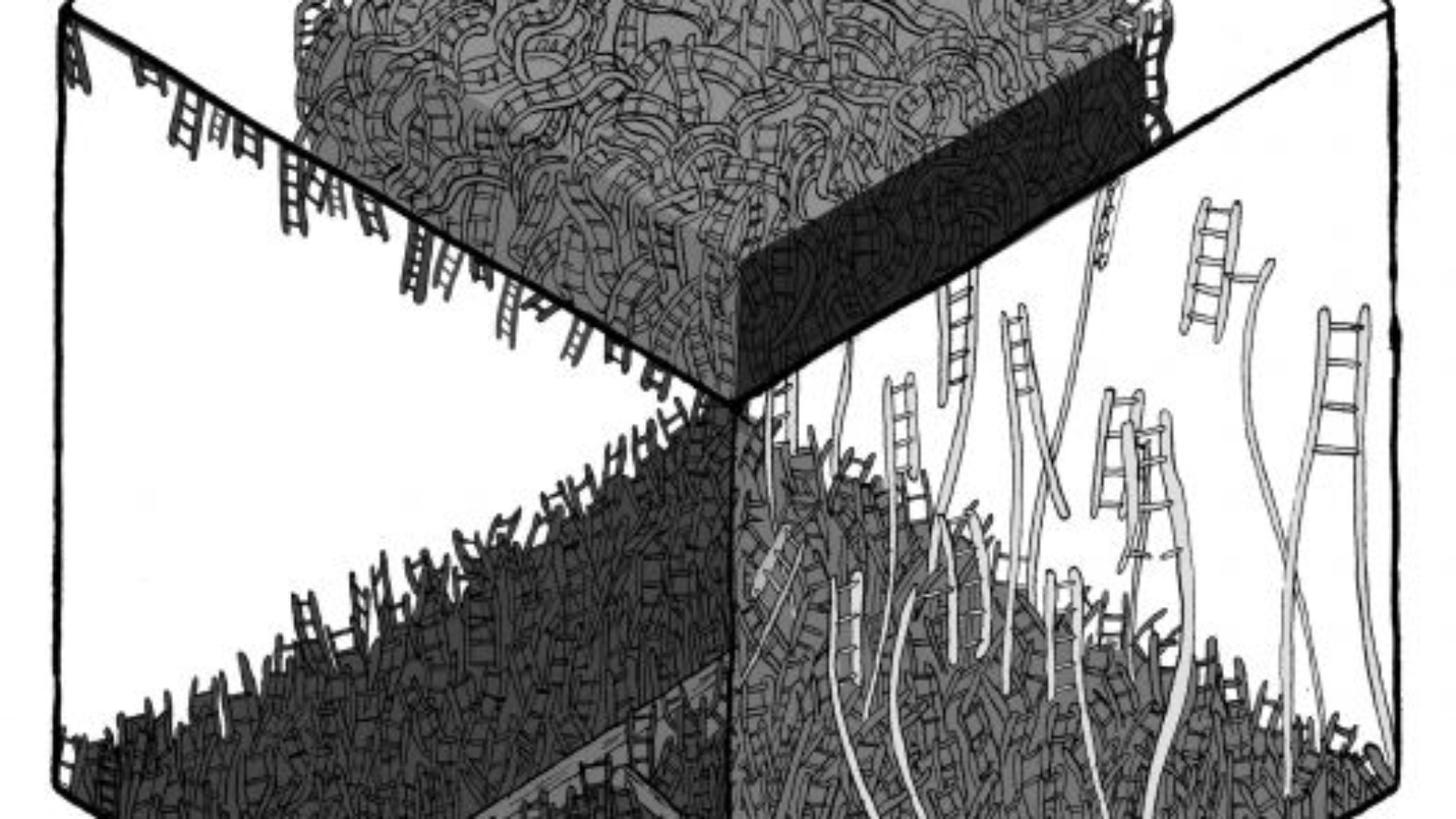

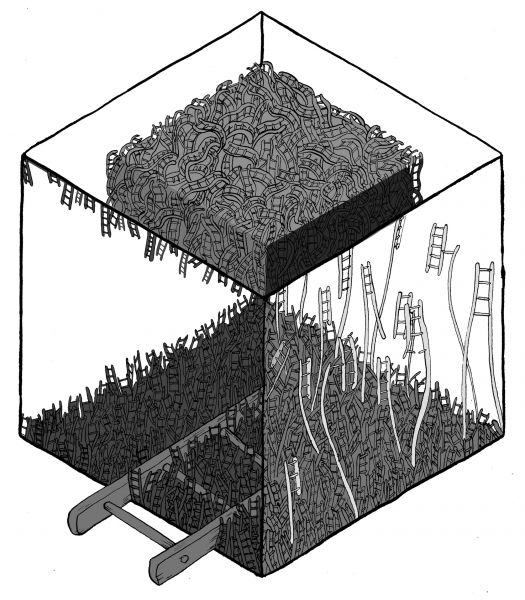

Critics point out that income distribution has remained virtually unchanged since the PRS was introduced in 2008 and that, according to World Bank figures, 3 out of 4 Liberians are still living below the poverty line. Yet Amara Konneh, the Minister of Planning and Economic Affairs, proudly lists a number of major rehabilitation projects—the building of roads, schools and hospitals—as evidence of the success of the PRS and the government’s plans for the development of a middle class in Africa’s oldest republic. “I think we’ve begun the process,” he says. “The economy is picking up and I believe that within the next five to 10 years we will see more people in Liberia climbing the ladder from poverty into the middle class.”

With the PRS set to expire in August, the government is introducing a new plan, Liberia Rising 2030, that aims to make Liberia a middle-income country—defined by the World Bank as a country with annual per capita income of around $4,000—within 18 years. The government has already met some important milestones. Last year GDP grew by 6.3 percent, up from 4.6 percent in 2009. This year the IMF projects the economy will grow 5.9 percent. Since 2006, income per capita has risen by a third.

In Konneh’s vision, Liberia Rising 2030 is a long-term project that will create a genuine middle class—people who will own their own homes and drive their own cars, provide their children with a decent education and quality healthcare, and possess enough disposable income to go on vacation. “There’s never been a Li- berian Dream,” Konneh says. “When you ask people about the good old days, they tell you about people driving Jaguars. Now, those are the people in the upper class. Then you have the lower class. There’s no middle,” he added. “So what we’re trying to say is, let’s create a Liberian Dream.”

So far, the government’s strategy to increase GDP has focused on foreign direct investment, an approach that some say has placed too little emphasis on developing the domestic economy. Foreign direct investment rose from $2.8 million in 2002 to $378 million in 2009, according to the World Bank. Despite the government’s efforts, however, the private investment landscape in Liberia remains relatively limited, with the exceptions of Arcelor Mittal, which mines iron ore, and a 2.5 million acre concession—the world’s largest rubber plantation—given to Firestone.

Nevertheless, Liberia is rich in natural resources, including timber, iron ore, gold and diamonds. Most of the population lives off the land, but there are also a number of large commercial farms. As more foreign investments come online, GDP is expected to rise. California-based Chevron, which acquired three deepwater blocks last September, will start looking for oil and gas off Liberia’s coasts by the end of the year, and employ Liberians in the process. Libe- ria also recently signed agreements with Indonesian palm oil company Golden Veroleum, Anadarko Petroleum and iron-ore miner China-Union Ltd.—all pledging to support the country’s social and economic development, but also eager to exploit its abundant natural resources.

These investments are an “expression of confidence in the leadership and future of Liberia, which are essential conditions to attract other major investors in all sectors of the economy,” President Johnson Sirleaf told The Wall Street Journal. “The creation of jobs and the revenue of possible oil finds will transform the econ- omy through infrastructure development.”

UNCHANGING BARRIERS

Despite five years of free-market policies that have drawn billions in public and private investments, life remains a struggle for Saye Guinkpa and thousands of others like him, with degrees and jobs but not much hope of advancement. Even as the private sector grows, a government job is still the only guaranteed path to upward mobility. After all, senior government staffers certainly don’t ride in shared taxis, and some can even afford to live in luxurious compounds with round-the-clock security and ocean views. But many talented young people like Guinkpa face seemingly immutable class barriers based on descent and skin color. Even after decades of violence and upheaval, lighter-skinned Americo-Liberians remain seated at the highest echelons of public life—a reality unchanged, so far, by the country’s nascent economic development.

The most that seems possible, for the moment, is a move out of what is effectively an urban underclass—one broad notch above subsistence—into what has the prospects of becoming a middle class, at least in Monrovia itself. For his part, Guinkpa remains undeterred by the fact that he has no immediate prospects for anything beyond that. “It motivates me to work harder,” he says.

Tecee Boley is a Liberian journalist who reports for Liberian Women’s Democracy Radio. This article was prepared with the assistance of New Narratives, a training program for women journalists in Africa.

*****

*****

INDONESIA: INNOVATION AND INVOCATION

By Aubrey Belford

JAKARTA—Twenty-five miles south of the city—far enough from the urban tangle for the air to be breathable—the unfinished Sentul City housing estates are, on the surface, familiar imitations of Western suburbia. A sign off the six-lane expressway leading to the development welcomes visitors to the “City of Ennovation.” Just alongside the development sits the Bellanova Country Mall, the entry point to a landscape of wide boulevards and meticulous landscaping, detached houses, and empty lots awaiting new construction.

The parking lot outside the mall is packed with sedans and SUVs. At an arcade inside, Rina Damayanti, a 29-year-old house- ife, watches as her husband, Aldi Rahman, thumbs the remote control of a miniature car carrying their 4 year-old son, Rosihan. She says life here beats the chaos of Jakarta—it is clean, comfortable and friendly.

“It’s better here,” she says. “There’s community life here. People make a priority of self-discipline and educating their kids.”

Just across the expressway, a similar housing development is rising. For the moment, this aspiring rival—called Bukit Az-Zikra, or “The Hill of Invocation”—comprises mostly rows of unbuilt homes. But its developers are confident that it will soon be a thriving, 400-home housing complex. Unlike the unabashedly worldly Sentul City, however, Bukit Az-Zikra will offer a vision of modernity and prosperity specifically intended for the observant Indonesian Muslim.

About 40 people already live in the complex, which will ultimately feature an office and shopping complex—based on “Islamic principles” of trade and business—to rival the mall across the expressway. All residents, when at the complex, are obliged to join prayers five times a day. Smoking is banned, and traditional Islamic dress is mandatory. Towering above the complex is the 10,000-person capacity Muammar Gaddafi Mosque—built with funding from the Libyan government’s international missionary arm.

Beside the mosque is a large, white-walled villa. This is the home of Arifin Il- ham, a celebrity television preacher and the public face of Bukit Az-Zikra. The housing complex’s ethos is based on the same message that Arifin brings to Indonesians in his television and radio sermons, and to the thousands-strong mass gatherings he holds for zikr, or Sufi-inspired chanting. Society is full of maksiat (immorality) and corruption, he argues, and in need of internal spiritual renewal. It is a message that resonates with Indonesia’s swelling middle class, who make up a key part of Arifin’s audience and are the explicit target market for his version of Islamicized suburbia.

Standing on his balcony as the call to prayer booms from the mosque, Arifin—a boyishly handsome man in his early 40s who speaks in a coarse growl—reflects on the needs of his followers. “They’re already successful. They already have the world. But—” Arifin breaks into English. “His soul—poor. All are fine, have money, popularity, success, but no heart.”

In other words, all this new money—and the secular suburban life on the other side of the expressway—is bad for the soul. Living alongside Muslims according to Islamic principles is the way to remove this taint. “Even charitable people, without an environment of brotherhood, can become weak,” Arifin says.

Arifin’s popularity is evidence that the growth of a middle class can take an unpredictable path. In Indonesia, the largest Muslim-majority country in the world, prosperity has not led inexorably to an embrace of secular values.

RICHER AND POORER

Known just a few years ago as a political and economic basket case, Indonesia today is stable, getting richer, and its middle class is exploding in size and influence. The world’s fourth most populous nation, with Southeast Asia’s biggest economy, Indonesia now boasts a per capita national income of $4,380—just enough to qualify as an “upper middle income” economy, according to the World Bank. Its economy grew by 6.1 percent last year and is drawing interest from investors faster than at any time since the 1997 Asian financial crisis crashed the economy, leading to the violent undoing of the 32-year Suharto dictatorship.

In Jakarta and in cities around the country, new cars are jamming roads. Colossal air-conditioned malls spring forth from former rice fields and cleared slums. The number of people spending at least six dollars a day jumped from just 1.7 percent of the population in 2003 to 6.5 percent in 2010, according to the World Bank. Of course, their share of the entire population of 238 million remains tiny, reflecting significant and growing economic inequalities. Still, Indonesia is a huge country, so even a small middle class translates to 15 million individuals buying cars, booking holidays, and saving for college degrees.

Working out just who comprises Indonesia’s middle class is an inexact science. Unlike similar emerging economies like China and India, little detailed study has been done on the subject, according to Enrique Blanco Armas, the senior Indonesia economist at the World Bank.

One issue is that Indonesia’s boom is not being driven by manufacturing or high-value services. “It’s definitely true that you don’t see the kind of job creation you see in other countries,” Armas says. “And that’s definitely linked to the pattern of growth in Indonesia, where the growth has mostly come from mining and commodities.”

At the bottom end of the socioeconomic hierarchy, tens of millions are moving out of poverty by working in mines or growing and selling palm oil. To move up further requires a decent education, as well as good luck, hard work, and family connections. Add to this, for some, the helping hands of nepotism and bribery.

But genuine social mobility is not yet a reality, according to Kecuk Suhariyanto, the director of analysis and development at Indonesia’s Central Statistics Agency. Kecuk supplies the raw data behind the World Bank figures, but claims that it doesn’t tell the whole story. (Indeed, he seemed apologetic about what he described as terrible deficien- cies in the information he can provide.)

Indonesia’s rich are likely much richer than the data suggests, says Kecuk. At the top end, the Bank estimates that the number of people spending more than $20 a day is 0.2 percent of the population. By Kecuk’s reckoning, that is probably a huge underestimate. Only in recent years has the government become serious about collecting income taxes and analyzing the data that yields. The richest Indonesians have, so far, been very good at keeping their wealth a secret.

“We can say that Indonesia’s economy is great—growth is 6.1 percent and our GDP is rising,” Kecuk says. “But if we look at the structure of things, the poor are staying poor, the rich are staying rich, and the number of those moving up is very tiny.”

That small group—the nascent middle class—has been the vanguard in a broader society shift that has surprised many observers. As Indonesia has become richer and more democratic, it has also become more religious and culturally conservative. For Christians, evangelical churches are supplanting more established orders. For the roughly 85 percent of Indonesians who are Muslim, an Arabized, reformist orthodoxy is gaining popularity over traditional Indonesian forms of religious practice, which mix Islam with elements of Hinduism, animism and Buddhism.

Plenty of factors contribute to this seeming paradox. But one issue stands out—corruption. Indonesia’s material success has left the country awash in dirty money. Transparency International ranks Indonesia 110th out of 178 nations on its Corruption Perceptions Index, making it cleaner than Mali but grubbier than Kazakhstan. Corruption is no secret, and it is not the reserve of an elite power group. Indeed, to be middle class in Indonesia is to be corruption’s victim, its beneficiary, or, commonly, both. The increasing religiosity of some upwardly mobile Indonesians seems, at least in part, to be a reaction to that reality.

BAD MUSLIM, GOOD BUSINESSMAN

Growing up in the Central Javanese city of Solo, Agus Prastawa was, by his own description, a bad Muslim. As a boy living in the heartland of Java’s traditional mys- ticism, a belief system known as Kejawen, Agus was given the weekly job of placing woven banana leaves and flowers at the door of his home, as nighttime offerings to local spirits—a common practice frowned upon by orthodox Muslims as shirk, or idolatry. Now middle-aged, Agus is a fairly wealthy man, running a small property development firm in Jakarta that builds homes and shopping complexes. He refuses to divulge his net worth, except to say he has “enough.”

As a young man, Agus attended university in the port city of Surabaya. As he gained an education and began to earn money, he gave little thought to embracing religion. But by 2003, he was growing disillusioned with the notoriously dirty nature of his chosen profession. After stumbling across Arifin Ilham’s sermons, Agus had a spiritual awakening.

Sitting around a table with other followers of Ustad—the honorific term by which Arifin’s followers refer to him—I venture a question about corruption, anticipating that things might get awkward. Instead, everyone chuckles in recognition. Dealing with grasping civil servants, who ask for bribes to speed up services or secure approval, is something that happens “every day,” Agus says. The result is an uncertain compromise—get a middleman to do the bribing, so at least you don’t have to directly hand over the cash. “I’ve been wanting to know, for my strength, for my belief, what I should do so it’s not wrong,” he says. “It’s a dilemma. After being around Ustad and Az-Zikra, I asked friends if what I was doing was wrong or right, and in the end I decided to use a ‘service person.’ We know it’s the wrong thing to do. We know in our religion you’ll go to hell, that it’s a sin. But if we say no, then our business can’t go on.”

This sort of skin-deep religiosity does not surprise Noorhaidi Hasan, an associate professor of Islam and politics at Indonesia’s Sunan Kalijaga State Islamic University. Arifin’s brand of religious teaching—personalized, accessible, and television friendly—is emblematic of a revival where many people choose to signal their faith by what they wear, how they dress and who they vote for. Noorhaidi calls this the “McDonaldization” of Islam.

“Those who react to globalization through Islam are not the deprived people, but the people who get the benefits of globalization themselves,” Noorhaidi says. Embracing this form of religiosity is a way of dealing with the anxieties that can come with new wealth and prosperity, and also represents an alternative, non-Westernized way to display rising status.

As a result, some in the middle class buy the West—Starbucks, KrispyKreme, and pop music. Others consume Islam—DVD sermons, veils and robes, a smattering of Arabic in everyday speech. Many mix the two.

THE NEXT STEP UP

This kind of a la carte religiosity—observance that doesn’t risk the bottom line—seems to survive the next step up the ladder, from middle class to genuinely wealthy. Down the hill from the Bukit Az-Zikra is the home of another Arifin follower, Denny Ernadie. The house is nothing grand, forsaking the immense size and neoclassical pomp favored by many Indonesian nouveaux riches. It is clean and comfortable, with a tiny courtyard out back that ensures a flow of air through the lounge room, where a flat screen television is tuned to Alif, a local Islamic cable channel that takes its name from the first letter of the Arabic alphabet. The house is strewn with souvenirs from Denny’s frequent trips abroad as a freelance consultant in the booming palm oil industry. On the couch, he has propped up a stuffed koala toy; in a nook where Denny does his prayers, a model of Kuala Lumpur’s Petronas Towers sits above a case holding Islamic books.

A decade ago, Denny quit his salaried position at an agribusiness firm—pushed, he recalls, by a persistent sense of spiritual emptiness. Cutting back on his hours by working as a freelancer, he abandoned an earlier life of sin—he declines to elaborate—and turned to religion. Denny thought he was trading money for spirituality by leaving his job, but in the end he need not have worried. Business never stopped coming in, and his income stayed high—something he attributes simply to the blessings of God.

“There is a verse in the Quran, that if we orient ourselves to religion—fully—then the world will follow,” he concludes.

In the coming years, many Indonesians will probably go the same way. Rising foreign investment and a likely pick-up in the growth of job-creating industries will allow Indonesia’s middle class to swell. Booming cities are becoming more cosmopolitan—Thai curries and Korean barbeque are growing trends. At the same time, liberal watchdogs point to a rising tide of religious intolerance. Local governments have appeased Islamists by passing laws discriminating against religious minorities and police have stood by while vigilantes bring violent morality campaigns to the streets.

As the middle class grows, it will likely combine both of Sentul’s versions of suburbia. At Arifin’s chanting sessions, 10,000 people at a time regularly pack the Bukit Az-Zikra mosque. Across the expressway, at the Sentul International Convention Center, the Canadian teen pop singer Justin Bieber played a sold-out show to screaming teens in April. The gleaming steel and glass convention center, which has a view of the mosque, fits the exact same number of people.

Aubrey Belford is a freelance reporter who writes about Asia from his base in Jakarta.

*****

*****

THE NETHERLANDS: PROSPERITY AND POPULISM

By Bas Heijne

AMSTERDAM—For the Dutch middle class, it appears, it is the best of times and the worst of times. Dutch men and women are almost completely happy about their lives, surveys suggest, with their satisfaction levels reaching an almost unimaginable 80 percent. When they open the front doors of their tidy houses and look outside, however, it’s another story altogether. Beyond their lives and families, they see a society that has gone wrong in all sorts of ways. The Dutch, it seems, are happy with their private lives, but decidedly unhappy with public life. Pollsters hear the same social ills cited repeatedly—unfriendliness and downright rudeness in public space, other parents raising unruly children, stifling bureaucracy, and a general lack of public spirit.

During the past decade or so, this form of discontent has created a surprisingly receptive audience among the Dutch middle class for a new breed of populist politicians who define the state of Dutch of society in apocalyptic terms. The first politician to recognize the opportunity this presented was a maverick named Pim Fortuyn, who built a devoted following by peddling a vision of a country in ruins, a nation whose identity was being wiped out by immigrants—especially Muslims—who refused to assimilate culturally. Without hesitation, Fortuyn compared himself to Moses, leading his people back to the Promised Land. In May 2002, just before national elections, his party was leading in the polls. Fortuyn was already choosing a suit for his inauguration as Prime Minister when he was shot to death in a parking lot outside a television studio, murdered by a radical environmentalist. In the aftermath of his shocking assassination, many of his followers called him a messiah, a redeemer.

Fortuyn’s natural successor is Geert Wilders, the leader of the Freedom Party. In spite of his flamboyantly bleached hair, Wilders is a much less exuberant figure. He is, however, far more radical in his views. So far, his movement has captured only about 15 percent of the vote. Yet his view of the state of Dutch society is widely shared, even by many of his political opponents. Wilders’ main concern is the so-called “Islamization” of Dutch society—a largely imaginary smothering of liberal Dutch values by an aggressive and oppressive Islam. Wilders’ activities consist mostly of an ongoing campaign of verbal attacks on Dutch Muslims, and many of his policy ideas are no more than cheap provocations, including a proposed tax on the Muslim headscarf, which he calls a kopvoddentax—a “head-rag tax.” (It sounds even worse in Dutch.)

While some of these antics are frowned upon even within Wilders’ own constituency, the basic tenets of his revolt have become completely mainstream. Crime rates continue to fall, and there has been no sharp decline in income, even during the global recession. Yet, all evidence to the contrary, conventional wisdom now holds that the Dutch middle class is in crisis. In a feat requiring no small amount of political talent, the populist right has fueled a form of social and political schizophrenia, fostering a support base of middle-class voters who are prosperous and content—but terrified and furious at the same time.

EGALITARIAN FANTASIES

The Dutch generally do not like to talk about class, and their collective prosperity has usually allowed them to avoid the topic. Per capita annual income is around $40,000, ten times the level that the World Bank considers “middle income” by global standards. The Low Countries have a long tradition of egalitarianism, and during the revolutionary 1960s, progressive ideas about equality became mainstream, as the country moved away from strict, stultifying divisions between various Christian denominations. These days, more or less everybody is supposed to be middle class in this nation of more than 16 million.

This is a fantasy. Though income disparity is modest compared to many other developed Western societies, there are quite a few fabulously wealthy Dutch citizens, while about 10 percent of the population lives below the official poverty line. Still, the image of an all-inclusive middle class endures. Very few Dutch citizens identify as “working class,” and on the other end of the spectrum, a great effort is made to avoid seeming too wealthy.

High-end retailers, like the Albert Heijn chain of supermarkets, cater to the expensive tastes of Dutch families with plenty of disposable income, but market a very specific kind of luxury—one that is accessible to all. Faced with public anger over a financial scandal at its parent company and the extremely generous compensation package that was promised to its CEO, Albert Heijn responded with an ad campaign meant to convey an ethos of modesty and averageness. The supermarket’s advertisements now feature a shop manager played by an actor who radiates “average Dutchman”—a balding, decidedly unglamorous figure. Even the royal family is supposed to behave as if it were middle class. On Queensday, the national holiday that celebrates the country’s monarchy, the royals visit small towns around the country and take part in traditional local festivities. They travel just the way their subjects might—by bus.

THE NEW POPULISTS

Wilders’ far-right movement has attracted voters who are beginning to doubt whether they are part of this supposedly expansive middle class. Many live in poorer neighborhoods in the bigger cities and feel left behind by economic growth and globalization. The genius of the new populists like Fortuyn and Wilders has been to tap into this anxiety without also engaging in economic populism—indeed, by ignoring economic issues almost entirely. What they are really exploiting is the fear of loss of identity—national, local, even existential. They have built a political movement around an anti-immigrant sentiment expressed in almost purely cultural terms, allowing them to attack and scapegoat the less affluent—the immigrant lower classes—without referring to class. In their vision, the problem with Muslim immigrants isn’t only that they commit crimes, or that they are a drain on the social-welfare system, or that they are dragging down standards of living. Instead, the real problem is Islam. The problem with poor immigrants isn’t the fact that they’re relatively poor, or that they are not middle-class enough—the problem is that they’re not “Dutch” enough.

The puzzled reaction of the political establishment to the fact that this message appeals to sizable sections of the Dutch electorate reveals a form of honest ignorance. The preoccupations of the populist right simply do not make sense to most mainstream leaders, and they have struggled in vain to find an effective response. This traditional political establishment now stands accused of betraying its own social-democratic principles. Its representatives still speak the language of equality and social commitment, but they are no longer perceived as caring for the common good. In the new populist mindset, the establishment is identified as the enemy within—committed to a vapid multiculturalism, forever stuck in 1968, when, in the view of Wilders and his followers, the old ideals of social democracy were betrayed by a group of romantic egotists lusting for power.

The irony, of course, is that the rise of right-wing populism is a powerful tribute to the real and unquestioned prosperity and economic stability of the Dutch middle class. After all, only a relatively prosperous electorate could afford to become obsessed with the “Islamization” of the Netherlands and the bureaucratic wastefulness of the European Union.

COMPETING NOSTALGIAS

What remains to be seen is whether this populist moment will truly bring a close to the decades-long Dutch experiment in progressive politics. The 1960s marked the end of the system of so-called “pillarization,” as many Dutch broke loose from a narrow sense of group identity derived from various denominations of Christianity (and for that matter, socialism)—the traditional sources of security and comfort. Dutch political culture became increasingly focused on personal freedom and the rejection of dogma and tradition. European unity, multiculturalism, and secularism became the new consensus values; personal emancipation, economic prosperity and security the new consensus political ideals. The Dutch developed a reputation for an almost radical form of tolerance—a relaxed attitude toward soft drugs, homosexuality, abortion and, later, euthanasia. To the surprise of many outside the Netherlands, these issues were resolved without much protest or even debate.

For those who applauded Dutch pragmatism and tolerance, the sudden rise of right-wing populism came as a big surprise. It should not have. With the total embrace of personal freedom and self-expression, the idea of what makes a coherent society was lost somewhere. Common social unifiers lost their appeal. Nationalism became deeply suspect. Other ideas of community—including class solidarity—were largely discarded as old-fashioned, folkloric or simply stupid. Identity could only be discussed as a personal matter. This development undeniably aided in the further emancipation of women, gays, blacks and immigrants. But it also undermined any attempts to foster social cohesion—creating a vacuum that right-wing populists like Fortuyn and Wilders and found quite easy to fill.

So far, the progressive-minded establishment has largely failed to counter the seemingly inexorable rise of populism. In the meantime, perhaps the most potent competition to the right-wing vision is coming not from within the political realm, but from the world of popular culture. There, a form of middle-class consciousness seems to be emerging, fueled by a vaguely nationalistic nostalgia for a less fragmented society—a nostalgia that is more sentimental than angry. Many television commercials now stress the “typically Dutch” qualities of products. A Dutch offshoot of the British cellular provider Vodafone promises a simple and honest “Dutch way” of dealing with customers. A new game show called I Love Holland attracts millions of viewers every week, even though it offers few (if any) prizes and no dramatic competitions. Contestants are quizzed about language, Dutch historical figures, and present-day media celebrities—all designed to promote a feeling of shared togetherness.

The most successful of these efforts is a “reality” show called Farmer Seeks Wife, which chronicles the romantic adventures of Dutch farmers searching for partners to share the burden of milking cows and harvesting crops. In its fifth season, the show broke viewership records. One episode garnered more than five million viewers, surpassing the audiences for news reports about natural disasters or royal weddings. In one way, it is a typical dating show. The farmers, mostly young men, appear as the Dutch equivalent of the Noble Savage—socially awkward and naïve about women and affairs of the heart. The women who participate come from the other end of Dutch society. They are worldly, tired of the dating game and looking for a much simpler life. These would be recognizable types in any modern society. But the real explanation of the show’s success is the vision of Dutch society it promotes—a Holland that is simple and humane, unthreatened by the dark forces of globalization and immigration. The innocence that radiates from the program may be cleverly manipulated by its makers, but its appeal serves as proof that the so-called crisis of the Dutch middle class has more to do with a desire for a shared identity than with economic inequality. The shows might be silly, and the entertainment executives behind them are hardly creative geniuses. But when it comes to understanding the Dutch public, they are light-years ahead of the country’s political establishment.

Bas Heijne, a Dutch novelist and essayist, is a columnist for NRC Handelsblad, a daily newspaper based in Rotterdam.

[Illustration: Marshall Hopkins]