As the global gap between the haves and the have-not grows ever wider, attention focuses on the top and the bottom of the socioeconomic spectrum. But what about the middle? Creating sustainable development might ultimately hinge on how we understand “middle class,” since achieving that vaguely defined status is now the ambition of billions of people. To find out what it means to be middle class, World Policy Journal chose to explore three countries at different levels of economic development—Liberia, with a per capita annual income of roughly $400; Indonesia, at around $4,000; and the Netherlands, at around $40,000. We asked writers in each country to profile its middle class—its aspirations, politics, and prospects.

*****

*****

INDONESIA: INNOVATION AND INVOCATION

By Aubrey Belford

JAKARTA—Twenty-five miles south of the city—far enough from the urban tangle for the air to be breathable—the unfinished Sentul City housing estates are, on the surface, familiar imitations of Western suburbia. A sign off the six-lane expressway leading to the development welcomes visitors to the “City of Ennovation.” Just alongside the development sits the Bellanova Country Mall, the entry point to a landscape of wide boulevards and meticulous landscaping, detached houses, and empty lots awaiting new construction.

The parking lot outside the mall is packed with sedans and SUVs. At an arcade inside, Rina Damayanti, a 29-year-old house- ife, watches as her husband, Aldi Rahman, thumbs the remote control of a miniature car carrying their 4 year-old son, Rosihan. She says life here beats the chaos of Jakarta—it is clean, comfortable and friendly.

“It’s better here,” she says. “There’s community life here. People make a priority of self-discipline and educating their kids.”

Just across the expressway, a similar housing development is rising. For the moment, this aspiring rival—called Bukit Az-Zikra, or “The Hill of Invocation”—comprises mostly rows of unbuilt homes. But its developers are confident that it will soon be a thriving, 400-home housing complex. Unlike the unabashedly worldly Sentul City, however, Bukit Az-Zikra will offer a vision of modernity and prosperity specifically intended for the observant Indonesian Muslim.

About 40 people already live in the complex, which will ultimately feature an office and shopping complex—based on “Islamic principles” of trade and business—to rival the mall across the expressway. All residents, when at the complex, are obliged to join prayers five times a day. Smoking is banned, and traditional Islamic dress is mandatory. Towering above the complex is the 10,000-person capacity Muammar Gaddafi Mosque—built with funding from the Libyan government’s international missionary arm.

Beside the mosque is a large, white-walled villa. This is the home of Arifin Il- ham, a celebrity television preacher and the public face of Bukit Az-Zikra. The housing complex’s ethos is based on the same message that Arifin brings to Indonesians in his television and radio sermons, and to the thousands-strong mass gatherings he holds for zikr, or Sufi-inspired chanting. Society is full of maksiat (immorality) and corruption, he argues, and in need of internal spiritual renewal. It is a message that resonates with Indonesia’s swelling middle class, who make up a key part of Arifin’s audience and are the explicit target market for his version of Islamicized suburbia.

Standing on his balcony as the call to prayer booms from the mosque, Arifin—a boyishly handsome man in his early 40s who speaks in a coarse growl—reflects on the needs of his followers. “They’re already successful. They already have the world. But—” Arifin breaks into English. “His soul—poor. All are fine, have money, popularity, success, but no heart.”

In other words, all this new money—and the secular suburban life on the other side of the expressway—is bad for the soul. Living alongside Muslims according to Islamic principles is the way to remove this taint. “Even charitable people, without an environment of brotherhood, can become weak,” Arifin says.

Arifin’s popularity is evidence that the growth of a middle class can take an unpredictable path. In Indonesia, the largest Muslim-majority country in the world, prosperity has not led inexorably to an embrace of secular values.

RICHER AND POORER

Known just a few years ago as a political and economic basket case, Indonesia today is stable, getting richer, and its middle class is exploding in size and influence. The world’s fourth most populous nation, with Southeast Asia’s biggest economy, Indonesia now boasts a per capita national income of $4,380—just enough to qualify as an “upper middle income” economy, according to the World Bank. Its economy grew by 6.1 percent last year and is drawing interest from investors faster than at any time since the 1997 Asian financial crisis crashed the economy, leading to the violent undoing of the 32-year Suharto dictatorship.

In Jakarta and in cities around the country, new cars are jamming roads. Colossal air-conditioned malls spring forth from former rice fields and cleared slums. The number of people spending at least six dollars a day jumped from just 1.7 percent of the population in 2003 to 6.5 percent in 2010, according to the World Bank. Of course, their share of the entire population of 238 million remains tiny, reflecting significant and growing economic inequalities. Still, Indonesia is a huge country, so even a small middle class translates to 15 million individuals buying cars, booking holidays, and saving for college degrees.

Working out just who comprises Indonesia’s middle class is an inexact science. Unlike similar emerging economies like China and India, little detailed study has been done on the subject, according to Enrique Blanco Armas, the senior Indonesia economist at the World Bank.

One issue is that Indonesia’s boom is not being driven by manufacturing or high-value services. “It’s definitely true that you don’t see the kind of job creation you see in other countries,” Armas says. “And that’s definitely linked to the pattern of growth in Indonesia, where the growth has mostly come from mining and commodities.”

At the bottom end of the socioeconomic hierarchy, tens of millions are moving out of poverty by working in mines or growing and selling palm oil. To move up further requires a decent education, as well as good luck, hard work, and family connections. Add to this, for some, the helping hands of nepotism and bribery.

But genuine social mobility is not yet a reality, according to Kecuk Suhariyanto, the director of analysis and development at Indonesia’s Central Statistics Agency. Kecuk supplies the raw data behind the World Bank figures, but claims that it doesn’t tell the whole story. (Indeed, he seemed apologetic about what he described as terrible deficien- cies in the information he can provide.)

Indonesia’s rich are likely much richer than the data suggests, says Kecuk. At the top end, the Bank estimates that the number of people spending more than $20 a day is 0.2 percent of the population. By Kecuk’s reckoning, that is probably a huge underestimate. Only in recent years has the government become serious about collecting income taxes and analyzing the data that yields. The richest Indonesians have, so far, been very good at keeping their wealth a secret.

“We can say that Indonesia’s economy is great—growth is 6.1 percent and our GDP is rising,” Kecuk says. “But if we look at the structure of things, the poor are staying poor, the rich are staying rich, and the number of those moving up is very tiny.”

That small group—the nascent middle class—has been the vanguard in a broader society shift that has surprised many observers. As Indonesia has become richer and more democratic, it has also become more religious and culturally conservative. For Christians, evangelical churches are supplanting more established orders. For the roughly 85 percent of Indonesians who are Muslim, an Arabized, reformist orthodoxy is gaining popularity over traditional Indonesian forms of religious practice, which mix Islam with elements of Hinduism, animism and Buddhism.

Plenty of factors contribute to this seeming paradox. But one issue stands out—corruption. Indonesia’s material success has left the country awash in dirty money. Transparency International ranks Indonesia 110th out of 178 nations on its Corruption Perceptions Index, making it cleaner than Mali but grubbier than Kazakhstan. Corruption is no secret, and it is not the reserve of an elite power group. Indeed, to be middle class in Indonesia is to be corruption’s victim, its beneficiary, or, commonly, both. The increasing religiosity of some upwardly mobile Indonesians seems, at least in part, to be a reaction to that reality.

BAD MUSLIM, GOOD BUSINESSMAN

Growing up in the Central Javanese city of Solo, Agus Prastawa was, by his own description, a bad Muslim. As a boy living in the heartland of Java’s traditional mys- ticism, a belief system known as Kejawen, Agus was given the weekly job of placing woven banana leaves and flowers at the door of his home, as nighttime offerings to local spirits—a common practice frowned upon by orthodox Muslims as shirk, or idolatry. Now middle-aged, Agus is a fairly wealthy man, running a small property development firm in Jakarta that builds homes and shopping complexes. He refuses to divulge his net worth, except to say he has “enough.”

As a young man, Agus attended university in the port city of Surabaya. As he gained an education and began to earn money, he gave little thought to embracing religion. But by 2003, he was growing disillusioned with the notoriously dirty nature of his chosen profession. After stumbling across Arifin Ilham’s sermons, Agus had a spiritual awakening.

Sitting around a table with other followers of Ustad—the honorific term by which Arifin’s followers refer to him—I venture a question about corruption, anticipating that things might get awkward. Instead, everyone chuckles in recognition. Dealing with grasping civil servants, who ask for bribes to speed up services or secure approval, is something that happens “every day,” Agus says. The result is an uncertain compromise—get a middleman to do the bribing, so at least you don’t have to directly hand over the cash. “I’ve been wanting to know, for my strength, for my belief, what I should do so it’s not wrong,” he says. “It’s a dilemma. After being around Ustad and Az-Zikra, I asked friends if what I was doing was wrong or right, and in the end I decided to use a ‘service person.’ We know it’s the wrong thing to do. We know in our religion you’ll go to hell, that it’s a sin. But if we say no, then our business can’t go on.”

This sort of skin-deep religiosity does not surprise Noorhaidi Hasan, an associate professor of Islam and politics at Indonesia’s Sunan Kalijaga State Islamic University. Arifin’s brand of religious teaching—personalized, accessible, and television friendly—is emblematic of a revival where many people choose to signal their faith by what they wear, how they dress and who they vote for. Noorhaidi calls this the “McDonaldization” of Islam.

“Those who react to globalization through Islam are not the deprived people, but the people who get the benefits of globalization themselves,” Noorhaidi says. Embracing this form of religiosity is a way of dealing with the anxieties that can come with new wealth and prosperity, and also represents an alternative, non-Westernized way to display rising status.

As a result, some in the middle class buy the West—Starbucks, KrispyKreme, and pop music. Others consume Islam—DVD sermons, veils and robes, a smattering of Arabic in everyday speech. Many mix the two.

THE NEXT STEP UP

This kind of a la carte religiosity—observance that doesn’t risk the bottom line—seems to survive the next step up the ladder, from middle class to genuinely wealthy. Down the hill from the Bukit Az-Zikra is the home of another Arifin follower, Denny Ernadie. The house is nothing grand, forsaking the immense size and neoclassical pomp favored by many Indonesian nouveaux riches. It is clean and comfortable, with a tiny courtyard out back that ensures a flow of air through the lounge room, where a flat screen television is tuned to Alif, a local Islamic cable channel that takes its name from the first letter of the Arabic alphabet. The house is strewn with souvenirs from Denny’s frequent trips abroad as a freelance consultant in the booming palm oil industry. On the couch, he has propped up a stuffed koala toy; in a nook where Denny does his prayers, a model of Kuala Lumpur’s Petronas Towers sits above a case holding Islamic books.

A decade ago, Denny quit his salaried position at an agribusiness firm—pushed, he recalls, by a persistent sense of spiritual emptiness. Cutting back on his hours by working as a freelancer, he abandoned an earlier life of sin—he declines to elaborate—and turned to religion. Denny thought he was trading money for spirituality by leaving his job, but in the end he need not have worried. Business never stopped coming in, and his income stayed high—something he attributes simply to the blessings of God.

“There is a verse in the Quran, that if we orient ourselves to religion—fully—then the world will follow,” he concludes.

In the coming years, many Indonesians will probably go the same way. Rising foreign investment and a likely pick-up in the growth of job-creating industries will allow Indonesia’s middle class to swell. Booming cities are becoming more cosmopolitan—Thai curries and Korean barbeque are growing trends. At the same time, liberal watchdogs point to a rising tide of religious intolerance. Local governments have appeased Islamists by passing laws discriminating against religious minorities and police have stood by while vigilantes bring violent morality campaigns to the streets.

As the middle class grows, it will likely combine both of Sentul’s versions of suburbia. At Arifin’s chanting sessions, 10,000 people at a time regularly pack the Bukit Az-Zikra mosque. Across the expressway, at the Sentul International Convention Center, the Canadian teen pop singer Justin Bieber played a sold-out show to screaming teens in April. The gleaming steel and glass convention center, which has a view of the mosque, fits the exact same number of people.

*****

*****

Aubrey Belford is a freelance reporter who writes about Asia from his base in Jakarta.

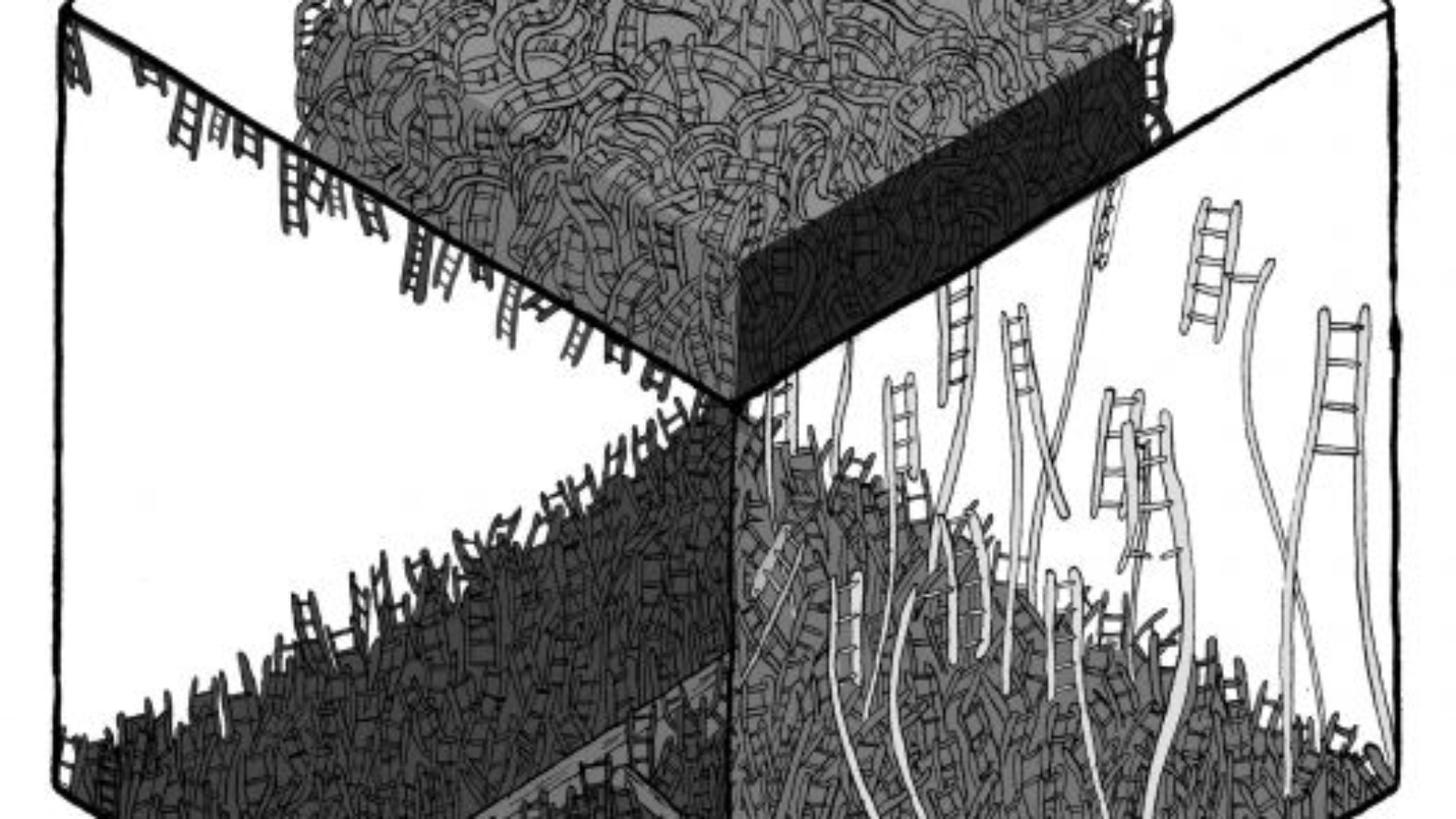

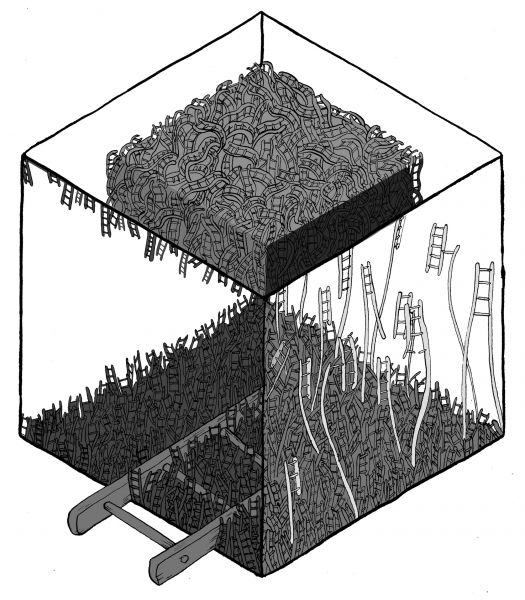

[Illustration courtesy of Marshall Hopkins]