This article is part of the Digital Freedom and Control Project produced exclusively for the World Policy Journal by students from the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.

By Joe Proudman

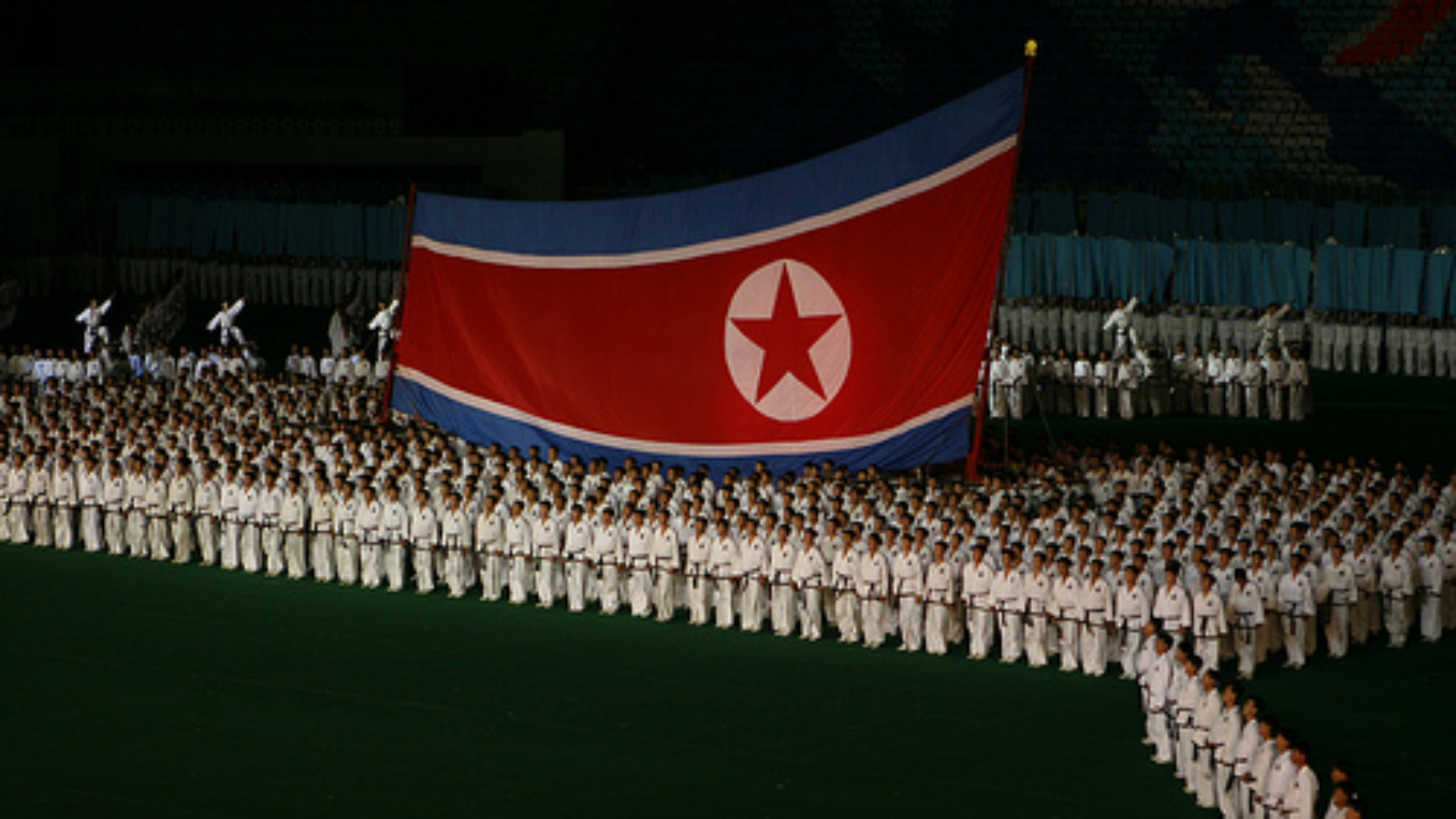

North Korea is known as one of the most repressive countries in the world. The government regularly tries to block information from reaching the outside world, and keep the outside world from seeping in. But even with such a strong grip on communication, the government has been unable to keep information from moving in and out.

U.S. policy makers are asking what, if any, role the Internet is playing in the flow of information. This was the question Senator Richard Lugar posed to a panel during a recent hearing of the Committee of Foreign Relations: “I'm curious to what information you have about so called social media or networks. To what extent are the young people, middle age or anyone in North Korea on the Internet or twittering or using iPads or what have you?”

The most specific answer to the senator’s question came from a witness before the panel, Marcus Noland, deputy director of the Peterson Institute for International Economics. “The number of people who have access to the Internet as we would understand it, is a very small group of the elite,” said Noland, author of Witness to Transformation, in a collection of interviews with North Korean refugees. “The North Korean approach to these issues is kind of characteristic of highly authoritarian regimes. On the one hand there is a desire to show that they also have the technology and a technological advanced society, on the other hand they are extreme concerned about the implications of these ways of communicating.”

Bruce Cummings, a Korea specialist at the University of Chicago, echoed Noland in an email interview: “In Pyongyang, where the elite live, many have access to good computers and the very controlled Internet. The average person outside Pyongyang barely knows what a computer looks like, I would guess. The tools of organizing dissent – Facebook, Twitter – don't exist.”

But there is some evidence that a few cracks of light are showing though in the notoriously secretive country. Charles K. Armstrong, a professor at Columbia University who specializes in modern history of Korea, says that the government’s control over media consumption has diminished over the past two decades, letting in more foreign media and the flow of information.

“This results from a combination of weakened state capacity after the economic implosion of the 1990s, so that the state no longer monitors radio use as it once did, as well as the use of new technologies – not so much the Internet, which is still mostly prohibited, but cell phones, of which there are now hundreds of thousands in the country,” he said.

Armstrong says that Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, as the regime of Kim Jong Il is officially known, may be facing tough choices between the country’s political goals, which are to keep a firm grip on information, and economic goals, which include improving technology.

“The Internet is not widely available in North Korea, and the government has tried to contain cell phone usage as much as possible. But it is impossible to have a functioning modern economy without the use of such technologies,” Armstrong said.

Developments inside the DPRK are reported by news sites based outside the country, which say they get their information from sources inside North Korea and the defectors who leave. Some of the websites devoted to North Korean news resemble blogs, such as North Korean Economy Watch or One Free Korea, which aggregate and comment on North Korean news.

Others, like Daily NK, purport to be actual news sites, producing original content on the DPRK. Daily NK English editor Eun Kyoung Kwon says the site was created by a group of people who were working for North Korean democratization and human rights. In 1999 they began the organization, Network for North Korean Democracy and Human Rights, to work with DPRK refugees. They needed an outlet to publish opinions and analyses on North Korea, and thus Daily NK was born.

“The mission of the Daily NK is to democratize North Korea and help them to establish a democratic country where the people can develop themselves, become the owner of the country, cooperate [with] each other for the country’s development,” Eun said. “In order to accomplish this mission, right now we need to release correct and real news and stories from North Korea so that outside people can understand the country correctly and the people.”

Daily NK, based in Seoul, South Korea, has established itself as a regular source of North Korean news. The Atlantic’s April 2011 issue credits the news site with scooping North Korea’s official newspaper, Rodong Sinmun, on Kim Jong Il’s annual message. The site is constantly updated with news from the North, in which sources are rarely named, but called for example, “citizens in Pyongsung” or “defector.” Nevertheless veteran North Korea watchers such as Cummings and Gordon Flake, question its reliability and accuracy at times.

Eun says that the intended audience is mainly South Koreans, Japanese, Chinese and English speaking readers who are trying to follow events in North Korea. He says that within North Korea, only the government has access to the news on the website.

Korea specialist Gordon Flake, testifying at a senate hearing in March, said short-wave radio broadcasts remain an important medium to provide news from the outside to North Koreans, especially along the Chinese border.

The one relatively new technology that is on the rise in North Korea, however, is cell phones, a technology that contributed to the deposing of leaders in Northern Africa.

“There are by my understanding some 260,000 to maybe 300,000 cell phones in operation in North Korea right now, the vast majority within Pyongyang, up and among the elite,” Flake said at the Senate hearing. “It’s an information transmission vehicle that did not exist before and among the elite who are most likely to be disillusioned, I think, probably in terms of the difference between expectations and reality. I think it's a very important factor in terms of understanding where North Korea is likely to go in the near future.”

A recent report by Yonhap News Agency cited a much higher number of over 430,000 cell phones being used last year – a figure released by the DPRK’s sole cell phone provider Orascom Telecom Holding, which is based out of Cairo.

“While few in number compared to countries like Egypt or Libya, let alone countries like China or South Korea,” Flake said in an email interview, “the rapid expansion of cell phones in North Korea represents a potential vehicle for communication that will likely continue to expand and which will be increasingly difficult for the government to control.”

In his book, Noland says that access to and consumption of foreign media by North Koreans has significantly increased. From interviews with refugees living in South Korea, that since 2006, he estimates that 50 percent of the population consumes foreign media, up from about 30 percent from 1998.

Although still limited, as North Korea continues to allow more technology, the information flow will continue to increase, shedding a little more light on the country.

*****

Joe Proudman is a journalist from California, where he worked for multiple news organizations including Bay Area News Group and Lee Enterprise. Most recently he interned at The New York Times and will intern as a photojournalist at The Star-Ledger in New Jersey this summer.

Photo courtesy of Flickr user Sheedl.

Digital Freedom and Control

Russia and Asia

Latin America

Middle East