This article is part of the Digital Freedom and Control Project produced exclusively for the World Policy Journal by students from the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.

By Umair Irfan

As new media platforms blur the distinction between activists and journalists, a new paradigm for reporting is being forged throughout the Middle East, starting in Egypt.

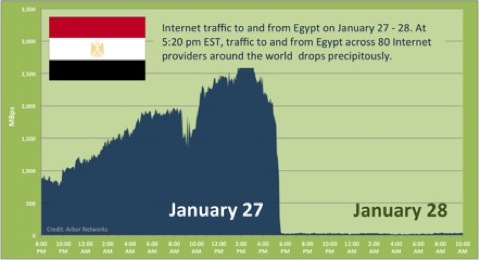

Widespread revolts in the Middle East spread throughout the region in part because information circumvented the government-controlled media. Through social media, as well as through websites and blogs, information about the extent and the nature of the protests was conveyed so effectively that in Egypt, the government shut down the country’s Internet entirely for a few days in January in an attempt to quell the unrest. On January 28, the Internet in Egypt went silent, shown in the graph below.

That, too, was unsuccessful.

As the protests against the Egyptian regime unfolded, a movement in what can be loosely defined as the field of journalism, gathered momentum to challenge state-controlled media directly, reform it, or bypass it altogether. Many of the new media reporters, bloggers and Twitterers, were more often driven by ideology and revolutionary fervor than by journalistic ideals.

With these factors at play, a model of journalism new to Egypt is emerging, though it’s not clear how free it will be or to what extent opinion and advocacy will drive the coverage. The United States, as well as other institutions around the world, are trying to influence the outcome by guiding activists and reporters through the intricacies of social media and providing pro-democracy civics training.

“I think what happened in the Middle East was entirely organic,” says Susannah Vila, director of content and outreach at Movements.org, a private non-profit that receives funding from the U.S. State Department. The group helps network activists while providing tools and training for social movements. “New technologies facilitated [the uprisings]. Technology made more people want to take action.”

Movements.org was formed in 2008 after a meeting in New York City, called the Alliance of Youth Movements Summit. The New York Times reports that it was attended by activists from Egypt who later helped lead the uprisings. The summit also produced “a field manual for youth empowerment,” which a State Department press release described as the antithesis to the Al Qaeda field manual. Seminars at the summit included “How To Build Transnational Social Movements Using New Technology,” “How To Use New Mobile Technologies,” and “How To Preserve Group Safety And Security.”

Egypt, as the largest Arab country, has highly influential media that is distributed throughout the Middle East, including television, radio and print. Until now those media were under tight state control. Social networking tools allowed reporters to operate outside of those controls, creating a parallel stream of information using digital media and a model for the region to follow.

“With the government tightly controlling what journalists could report in mainstream, bloggers can cross many of the red lines un-punished, to a certain extent,” says Sarah El Sirgany, deputy editor for the Daily News Egypt, speaking to Pakinam Amer, another Egyptian reporter. El Sirgany also covered the uprisings earlier this year. “While [bloggers] don’t get sued or threatened by hefty fines or lengthy jail sentences, they are subject to arbitrary arrest and detention without charge.”

Even pro-government media wavered in their support for Mubarak and signaled a desire for reform. Early in February, Al-Ahram, Egypt’s second-oldest newspaper, expressed solidarity with the uprisings shortly after Ahmed Mohamed Mahmoud, a reporter for an Al-Ahram affiliate, was shot dead after filming protests with his mobile phone.

Nonetheless, the traditional Egyptian press is far from free. In 2009, an Egyptian court banned a magazine for blasphemy. In its ruling, the court said "Freedom of press… should be used responsibly and not touch on the basic foundations of Egyptian society, and family, religion and morals."

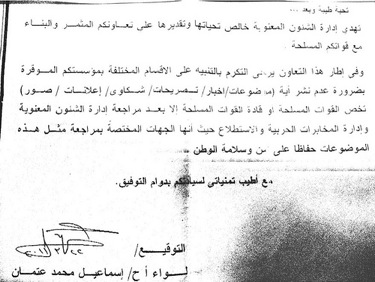

Even after Mubarak’s abdication, the Egyptian military is requiring all print reporters to have approval before publishing any reports pertaining to the military. This was highlighted in a memorandum issued to Egyptian media outlets by Major-General Ismail Muhammad Etman in late March. A number of activists and journalists have been imprisoned by the military, with one blogger, Maikel Nabil Sanad, sentenced to three years in prison for insulting the military.

English translation:

The Morale Affairs Department expresses its sincere greetings and its appreciation of your fruitful and constructive co-operation with your Armed Forces.

In light of this co-operation, we kindly request that you notify the different departments at your estimable institution of the necessity to refrain from publishing any items –stories, news, announcements, complaints, advertisement, pictures—pertaining to the Armed Forces or to Commanders of the Armed Forces without first referring to the Morale Affairs Department and the Department of Military Intelligence and Information Gathering, as these are the authorities specialized in reviewing such matters, and that is to ensure the safety and security of the homeland.

With my best wishes for your continued success,

Major-General Ismail Muhammad Etman 22/03/2011

With such restrictions, the need for improved journalism skills is great. Shortly before the uprisings in January, UNESCO launched a project with Cairo University to develop a model for training journalists. The project studies was intended to study how journalism is taught in Egypt and to issue recommendations. The pro-democracy movement in Egypt has opened up new vistas for the project.

“We know that journalism, and the educational programs that enable individuals to practice and upgrade their journalistic skills, are essential tools for the underpinning of key democratic principles that are fundamental to the development of every country,” says Abdul Waheed Khan, an Assistant Director-General at UNESCO.

During the uprisings, UNESCO’s central office was very vocal about the need for the government to respect the rights of journalists and strongly condemned Mahmoud’s killing. "Silencing the media or attempting to intimidate them is an unacceptable assault on the right of citizens to be informed," said the Director General of UNESCO, Irina Bokova.

After Mubarak stepped down, UNESCO’s Cairo office began to offer workshops and classes for active journalists, focusing on how to operate outside of state control. Led by The Guardian’s Reader’s Editor Chris Elliot, one workshop in April highlighted the importance of acknowledging mistakes in reporting and issuing corrections. In addition, the workshop covered the ethics of social media and the distinctions between opinion and reporting.

In the wake of the upheavals, the U.S. government established ways of communicating directly with journalists and denizens of the Middle East to promote its messages and ideals. The State Department started an Arabic Twitter feed, @USAbilAraby, shortly after Mubarak stepped down. The feed posts statements by President Obama and Secretary Clinton that pertain to the Arab world and currently has over 7,000 followers. A similar Twitter account was established in Farsi.

America’s history of supporting Mubarak, as well as other ousted leaders in the Middle East, has led to some skepticism in the region about its intentions. Non-profits like Movements.org are trying to combat this skepticism through a more open engagement with local activists and reporters. “You try to as transparent as possible,” says Vila, who points out that the United States have shifted their approach in dealing with the Middle East. “I think that if you look at the past 20 years, there has been an increased interest in democracy promotion [in U.S. policy].”

The confluence of activism, journalism, outside guidance, and domestic pressures has created a novel approach to Egyptian news coverage. “The sources of news are not limited to wire services or established news websites, but expand to include the product of civil journalists’ work,” says Sarah El Sirgany. “Having a Twitter page combining major newspapers’ headlines with the latest updates of bloggers and other civil journalists has become a necessity of any news room.”

The online aspect of journalism will still require state support, since Internet infrastructure remains in the hands of the government. With the democratization of reporting and messaging tools through the web, the barriers between those seeking to promote a message and those seeking to report are disappearing. Whether this will result in the best obtainable version of the truth remains to be seen.

As El Sirgany recalls, hearing the news Mubarak’s resignation: “It was short enough to fit in a Tweet. But it was mighty.”

*****

Umair Irfan is a recent graduate of Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. He is now working for ClimateWire in Washington D.C.

Photo “Blinded by Journalism” by Ahmad Hammoud.

Digital Freedom and Control

Russia and Asia

Latin America

Middle East