This article is part of the Digital Freedom and Control Project produced exclusively for the World Policy Journal by students from the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.

By Mariya Karimjee and Lakshmi Kumaraswami

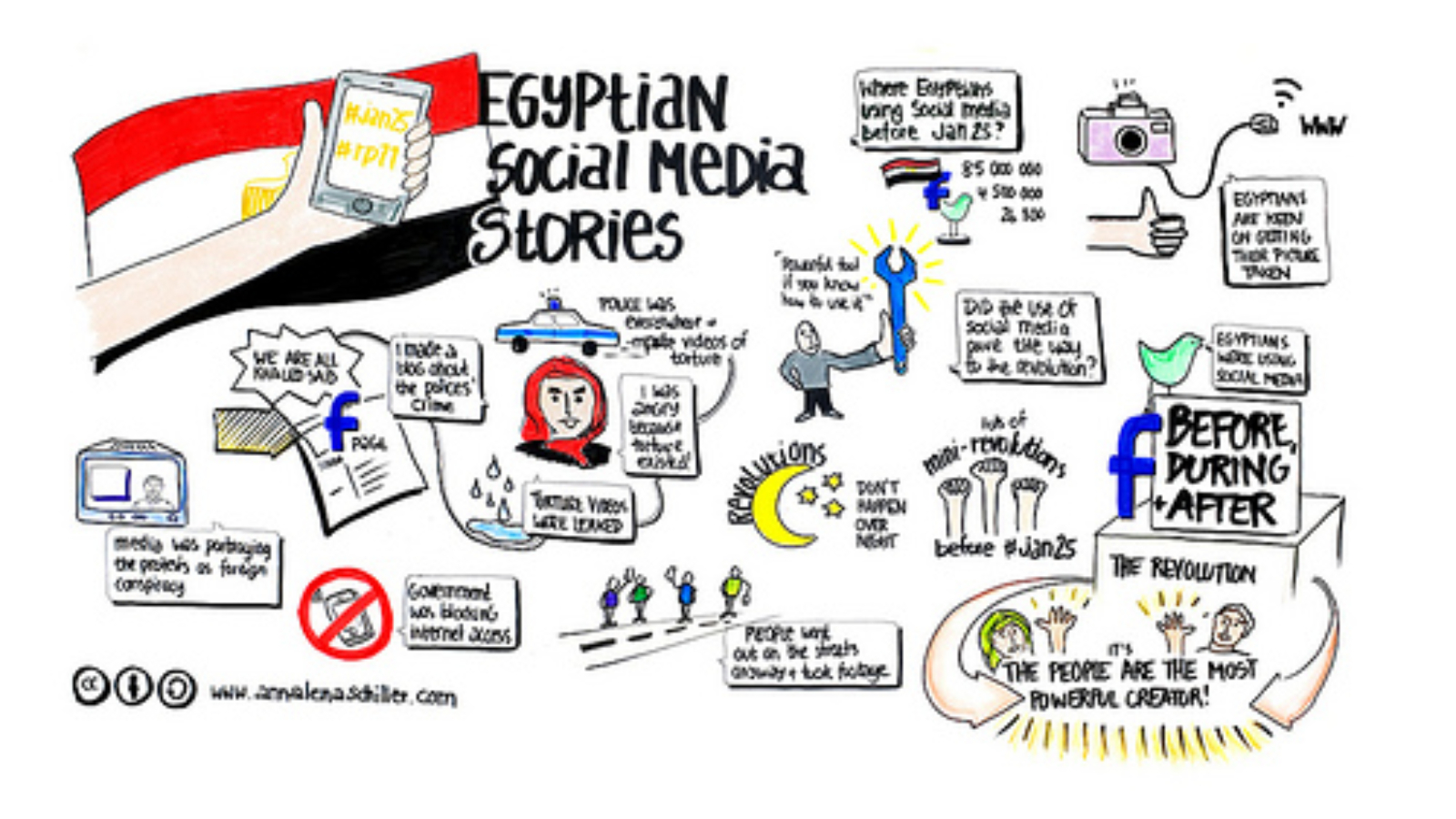

The number of registered Facebook users in the Middle East at the beginning of 2010 was 11.9 million. By the end of the year, the number had almost doubled to 21.3 million.

Those were mere statistics, until the uprisings in Tunisia, Egypt, Bahrain and other countries, in which commentators speculated how much social media, especially Facebook, had played a role. There is much debate, however, about how significant that role was in the revolutions and protests.

Some analysts say it was indispensable. “The whole process of mobility was virtual, Internet is what has brought people together in this protest,” said Amr Hamzawy, research director at the Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut, in an interview with Egypt News.

Clay Shirky, a professor at NYU and a Twitter evangelist, is the most public advocate of social media’s influence in the protests. He argued in Foreign Affairs that digital networks such as Facebook and Twitter made the protests possible by allowing information to spread and in effect broke down barriers to free speech in countries where it may not have been possible otherwise. Social media were also instrumental in spreading the protests from country to country.

Governments, he argued, have feared large, organized groups, but underestimated the power of individual communication on media such as Twitter and Facebook. Because the governments did not control the transmission of information on these platforms, the details and images of protests in other countries were allowed to spread. Furthermore, said Shirky, this information was then received and reused by television and “traditional” media, making large numbers of people aware of the protests and breaking the barrier of fear that might have kept them from joining.

Ethan Zuckerman, a senior researcher for the Berkman Center for Internet and Society, along with other analysts, made the argument for social media skepticism. He argued that Internet users were influential in organizing these protests, but that this is only part of the story. “I don't think they could have happened without MEDIA – the combination of Al Jazeera, social media and other media forces,” Zuckerman said in an email.

Jillian York, another researcher at the Berkman Center agrees. Social media was not the catalyst for the uprising, she argued.

“In Tunisia, it was unemployment and poverty and the self-immolation of young Mohammed Bouazizi that spurred citizens to take to the streets, eventually causing President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali to flee,” she wrote in The European Magazine. York added, “It’s fair to say that the Internet has changed the game, but to credit it for revolutions is disingenuous and takes credit away from the blood, sweat, and tear gas that make up a revolution.”

Malcolm Gladwell, author of The Tipping Point, wrote in The New Yorker, that people were protesting and bringing down governments long before Facebook or the Internet were invented. After the youth protests in Moldova in 2009 against their communist government, Gladwell argued that social media were getting far too much recognition.

Following the protests in Tunisia, he addressed the issue again in another New Yorker article. He argued that people make revolutions using any method or technology available to them, rather than the other way around. Unlike Shirky who believes that the protests were only possible because of social media, Gladwell believes that social media was a minor agent in the protests. “Barely anyone in East Germany in the nineteen-eighties had a phone…and in the French Revolution the crowd in the streets spoke to one another with that strange, today largely unknown instrument known as the human voice," wrote Gladwell.

Rawya Rageh, an Al Jazeera correspondent and Egyptian citizen witnessed the protestors on the ground in Tahrir Square. She noted that it was on Jan. 28, when the Internet was completely shut down, that the largest number of people took to the streets. “Social media did play a role in mobilizing Egyptian protesters during the uprising, but describing this as a 'Twitter and Facebook revolution' is an inaccurate description.”

Many of the people who took part in the protests from the very first day were Egyptians who didn’t have Internet access. “The majority were just ordinary people fed up with their living conditions, chronic unemployment and rampant corruption,” said Rageh.

While social networking media such as Facebook and Twitter were indisputably a factor of some importance in mobilizing the revolutions in Egypt and Tunisia, the same cannot be said about Yemen, which has lower internet penetration and literacy rates. Some Facebook events set up to publicize the demonstrations in Sana’a, had many attendees online, but few offline; when some groups on Facebook urged an anti-government rally on February 10, only about 100 people showed up.

According to Ethan Zuckerman, the Shirky-Gladwell debate creates a false dichotomy. “In Tunisia, social media helped document the protests—videos went up on Facebook, got amplified by sites like Nawaat.org, then ended up on Al Jazeera. Once they were on Jazeera, it was easy for Tunisians to see what their neighbors were doing and decide to join in,” he said. But it is a massive oversimplification, he said, to think of this as a Twitter or Facebook revolution, since it was not just social media that drove the uprisings, but the media in general. Zuckerman understands all media as working together.

“It's not just Facebook – it's an ecosystem that includes mobile phone video cameras, participatory media platforms, opposition media aggregators and satellite channels. It's a mistake to try to pin the story all on one technology.”

*****

Mariya Karimjee and Lakshmi Kumaraswami are recent graduates of Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.

Image courtesy of Flickr user Fraulein Schiller.

Digital Freedom and Control

Russia and Asia

Latin America

Middle East