By Jake Adelstein

TOKYO—In June 2007, as Japan’s upper house elections were drawing near, the nation’s largest organized crime group—the 40,000 member Yamaguchi-gumi—decided to throw its support behind the country’s second leading political party, the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ). Fifteen of the Yamaguchi-gumi’s top-ranking members made the decision behind closed doors. After the die was cast, a meeting was convened at the sprawling Yamaguchi-gumi headquarters, which take up two square blocks in Kobe.

The gang’s most powerful executive members, the jikisan, were summoned from throughout Japan and ordered to put their full support behind the DPJ. The message was simple. “We’ve worked out a deal with a senior member of the DPJ. We help them get elected and they keep a criminal conspiracy law, the kyobozai, off the books for a few more years,” one insider said. The next month, calls went out from Yamaguchi-gumi headquarters to the heads of each local branch across the country. In Tokyo, even the conservative boss Goto Tadamasa, leader of the 1,000 strong Yamaguchi-gumi unit called the Goto-gumi, told his people, “We’re backing DPJ. Whatever resources you have available to help the local DPJ representative win, put them to work.” Bosses of the Inagawa-kai, Japan’s third largest organized crime group (10,000 members), met in an entertainment complex they own in Yokohama, and announced to board members that the Inagawa-kai would support DPJ as well. At the same time, the yakuza allegedly struck a deal with Mindan and Chosensoren— political and social organizations that lobby for the rights and interests of Japanese of Korean descent—to support the DPJ. Party leaders, in turn, promised both groups that they would strive to get Japanese- Koreans with permanent residence equal voting rights when they took office. According to the National Police Agency [NPA], of the more than 86,000 yakuza members in Japan, a third are of Korean descent.

An Unprecedented Deal

For decades, Japan’s vast, homegrown mafia network has exercised powerful control over the inner workings of domestic politics. With antecedents as far back as the early Tokugawa period in the seventeenth century, today’s yakuza came of age after World War II, calling themselves ninkyo dantai, or chivalrous organizations. Japan’s longest ruling party, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), has dominated Japanese politics since it was founded at the same time. The LDP couldn’t have existed without the financial support of Yoshio Kodama, a right-wing activist and industrialist with strong yakuza connections. From its earliest days, gang bosses funded and supported LDP candidates and elected officers, and were rewarded with public works projects, political favors and an agreement that no serious crackdown on the yakuza would take place. Their existence would remain effectively legal. The Japan Federation of Lawyers (Nichibenren) has argued for years that while the Japanese government officially recognizes 22 yakuza outfits and regulates them, the act of recognition itself legitimizes the organizations. For decades the federation has called for an across-the-board ban on the existence of organized crime groups.

Until the 1990s, the yakuza were tolerated, even accepted in Japanese society as fraternal organizations, like Kiwanis clubs.

Sokka Gakkai, a religious organization represented by the political party Komeito, used the Goto-gumi, to keep its party strong and squelch dissent. Tadamasa, the Goto-gumi boss, explicitly discusses these ties in his recently published autobiography. Some LDP senators and cabinet ministers used yakuza enforcers to deal with bad debts and bounced checks. Wealthy senators such as Eitaro Itoyama used organized crime to cover up scandals and increase their wealth.

In the summer of 2001 Tadamasa, the Goto-gumi leader, was able to get into the United States for a liver transplant using Hoshi Hitoshi, a former aide to ex-Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi (LDP). Hitoshi approached the FBI via the US Embassy in Tokyo to work out an information for visa deal, leveraging the FBI's concerns on yakuza assets in the United States. Tadamasa brags of his connections to Kishi in his memoirs and did not provide all the information promised, leading U.S. authorities to bar another crime boss, Inagawa Chihiro, from entering the U.S. despite former LDP Secretary General Makoto Koga's pleas to U.S. officials.

But a seismic shift is underway in Japanese politics. For the first time in modern history, the yakuza have swapped allegiances. Two of Japan’s three largest crime organizations adopted the DPJ as their official party in a single stroke. The most powerful, the Yamaguchi-gumi, has brought voters, funding and “diplomatic” aid to the DPJ. This spring it helped the DPJ suppress civil dissent and gather support for the party’s proposal to move some American military facilities to Tokunoshima, an island in Kagoshima prefecture. The Yamaguchi-gumi orchestrated this through right-wing groups with local gang connections.

Such political groups are often used as tools of the yakuza, because freedom of assembly and speech laws allow them to coerce and disturb under the guise of political activity. When it came to power, the DPJ promised to pay attention to Okinawa’s U.S. military burden. Their request to the Americans to move some training exercises made good on that promise, while the Yamaguchi-gumi will likely profit from any new construction for the Tokunoshima facilities through bid rigging and kickbacks.

The Democratic Party of Japan was actually created in 1998, when reform-minded politicians from a number of opposition parties united, hoping to create an authentic opposition party capable of taking over from the ruling LDP. Few ever thought it would happen. Yet during the 2007 House of Councilors election, the DPJ won a huge number of seats, seizing control of the upper house of the Japanese parliament, or Diet. In 2009, under the leadership of Yukio Hatoyama and still backed by the yakuza, the DPJ won the general election by a landslide— the first change in Japanese government since the two-party system was adopted at the end of World War II. Hatoyama became the prime minister. The Yamaguchi-gumi had picked a winner.

In Broad Daylight

The yakuza are not confined to the shadows. They have office buildings, business cards, even fan magazines. They are heavily involved in construction (including public works projects), bid-rigging, real estate, extortion, blackmail, stock manipulation, gambling, human trafficking and the sex trade. They often use civilians to front their operations, taking out small business loans offered by the Japanese government and defaulting on payment. A financial analyst for a major investment bank in Japan estimates that 40 percent of all small business loans made nationwide went to companies created by the yakuza. Sources within the Tokyo Police Department estimate that at least 10 percent of all defaulted loans by the New Bank Tokyo (Shinginko Tokyo) had been made to organized crime enterprises.

In the late 1990s, the yakuza got into finance. Yamaguchi-gumi leader Masaru Takumi set the example as first of a new breed— the economic yakuza—observing that “from now on, the first thing a yakuza needs to do when he gets up in the morning is read the business section of the newspaper.” The Yamaguchi-gumi have been particularly interested in venture firms, buying up stocks and creating markets with hundreds of listed companies, all with mob connections. In the 2008 edition of their annual report on crime in Japan, the National Police Agency (NPA) added a special section on the rapid emergence of organized crime into Japan’s securities and financial markets. The NPA report was a surprisingly stark admission of the crisis, with the police conceding they were fighting to protect Japan’s international reputation as much as its economy. The report went on to state that the yakuza had become frequent stock-traders, adept at market manipulation. The NPA warned that the yakuza’s move from “old-fashioned” crime rackets like drugs and prostitution, to mainstream financial markets is “a disease that will shake the foundations of the economy.”

By 2008, the Securities and Exchange Surveillance Commission, the NPA and the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department had compiled a watch list of hundreds of companies suspected of direct or indirect links to mafia money. The issue had become so bad that the Osaka Stock Exchange was forced to introduce an entirely new screening system to establish which companies have direct mob links or large quantities of yakuza cash on their shareholder register. More than 50 companies faced the threat of delisting. In May 2010, the NPA finally agreed to begin sharing their internal lists of known yakuza members with financial institutions, in an effort to halt a further advance of organized crime into Japan’s financial spheres.

No Mafiosi

The yakuza tend to be gentler than their Italian cousins. In general, they are not involved in theft, burglary, armed robbery, or other street crimes. Inter-yakuza gang wars do break out on a semi-regular basis, but rarely do they attack public figures. In 1992, the film director Itami Juzo was slashed in front of his home after he made a film lampooning the yakuza and, worse still, demonstrating how the gangs could be driven out of civilian affairs using a lawyer. In April 2007, before the DJP and the Yamaguchi-gumi had struck their deal, the mayor of Nagasaki— an independent who had been backed by the DJP and Komeito—was assassinated by a Yamaguchi-gumi crime boss for allegedly interfering with yakuza attempts to win a share of public works contracts. Despite this, leaders of the ruling LDP party tolerated the yakuza’s existence for years, sometimes even socializing with them.

The yakuza are not confined to the shadows. They have office buildings, business cards, even fan magazines.

By conspiring and working with the LDP, the yakuza made sure that no major addition to the law was put on the books, and that their existence itself wasn’t banned. At the same time, they gained access to information that allowed them to participate in bid rigging for public works projects and suppress proposed laws that might cut into their revenue. For example, human trafficking regulations were long opposed by the Geinoren, the Association of Foreign Entertainment Brokers. Some members of this lobbying group were yakuza, and the group held its annual meetings at LDP headquarters. Former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was once a guest speaker. Former LDP Senator Kobayashi Akira directly pressured the head of Tokyo Immigration to stop raiding Philippine sex clubs. Eventually, heavy criticism from the United States and international pressure forced Japan to pass significant laws against sex-trafficking.

A Growing Problem

Until the 1990s, the yakuza were tolerated, even accepted in Japanese society as fraternal organizations, like Kiwanis clubs. They put their logos on office doors, held press conferences and intimidated the general public with impunity. In 1992, the Japanese government passed the first openly anti-mob legislation and larger yakuza groups were classified as “designated violent groups.” The new statutes limited yakuza activities and cut into their protection rackets. So, as Japan’s financial and real-estate bubbles ballooned, the yakuza shifted into real estate and other legitimate businesses, and the government continued to revise the law to limit their power. Still, no legislative fiat has made membership in a criminal organization outright illegal, or has given police the anti-mob tools long considered crucial in other countries. There is no wiretapping, plea bargaining, or witness protection program in Japan. As a result, the leaders of each organization are well-known and often public figures. Each New Year’s day, the de facto head of the Yamaguchi-gumi, Kiyoshi Takayama, distributes envelopes filled with cash to neighborhood children in Kobe, in a much photographed bid to show his inner Santa.

In addition to major yakuza groups across Japan today, there are perhaps 100 minor gangs. Some began as coalitions of professional gamblers and illegal operators. The Inagawa-kai, for example, has factions in 22 of Japan’s local governments and is managed by a corporate board, which determines the position and title of each member and the status of each faction. The board also has the power to raise or lower the monthly association dues, which can be as high as $30,000 a month per faction. The chairman of the board is generally the most powerful person in the organization. Others, like the Yamaguchi-gumi, began as quasi labor unions for dock workers.

Almost all yakuza are structured like a pyramid, with a first, second and third tier. Within each group is a motherless family. Young recruits pledge their allegiance to the oyabun (a father figure, of sorts), and the oyabun of the third tier reports to an oyabun above  him, and so on. Alliances are made in ritual ceremonies, with yakuza pairing off as equals (kyodai or brothers) or in a teacher and disciple relationship. The oyabun commands absolute loyalty. The top tier of all organizations receive membership dues from the lower ranking tiers, and headquarters use the money to fund large-scale operations like stock market manipulation or loan-shark shops. For the Yamaguchi-gumi, the headquarters can, at times, function like a private equity group, putting up capital for large-scale fraud schemes. When Lehman Brothers Japan was defrauded of $350 million in 2008, police believed that the Yamaguchi-gumi provided some of the funding to make the deal work.

him, and so on. Alliances are made in ritual ceremonies, with yakuza pairing off as equals (kyodai or brothers) or in a teacher and disciple relationship. The oyabun commands absolute loyalty. The top tier of all organizations receive membership dues from the lower ranking tiers, and headquarters use the money to fund large-scale operations like stock market manipulation or loan-shark shops. For the Yamaguchi-gumi, the headquarters can, at times, function like a private equity group, putting up capital for large-scale fraud schemes. When Lehman Brothers Japan was defrauded of $350 million in 2008, police believed that the Yamaguchi-gumi provided some of the funding to make the deal work.

With 86,000 gangsters in the country’s crime syndicates, the yakuza today are many times the strength of the American mafia at its peak. The most powerful concentration of the Italian-American crime networks, in New York, is estimated to have fallen from 3,000 members in 1970 to just 1,200 members today. Yet across Japan, the yakuza are only growing. They are such a persistent problem in civil affairs that an entire industry of lawyers specializes in dealing with criminal syndicates. In the city of Nagoya, home to the Kodo-kai, a 4,000-member Yamaguchi-gumi unit, the Nagoya Lawyer’s

Association advises businesses and landlords to insert an “organized-crime exclusionary clause” into their contracts, and issued a manual entitled “Organized Crime Front Companies: What They Are and How to Deal With Them.” Large real estate companies have even been known to pay yakuza enforcers to assist in evicting tenants who refuse to leave. In March 2008, the Suruga Corporation—a real estate investment firm once listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange— was revealed to have paid over $157 million to Yamaguchi-gumi affiliates over several years to remove tenants from properties they wanted to buy. A former bureaucrat and prosecutor from the Organized Crime Control Bureau of the national police sat on Suruga’s board of directors.

Married to the Mob

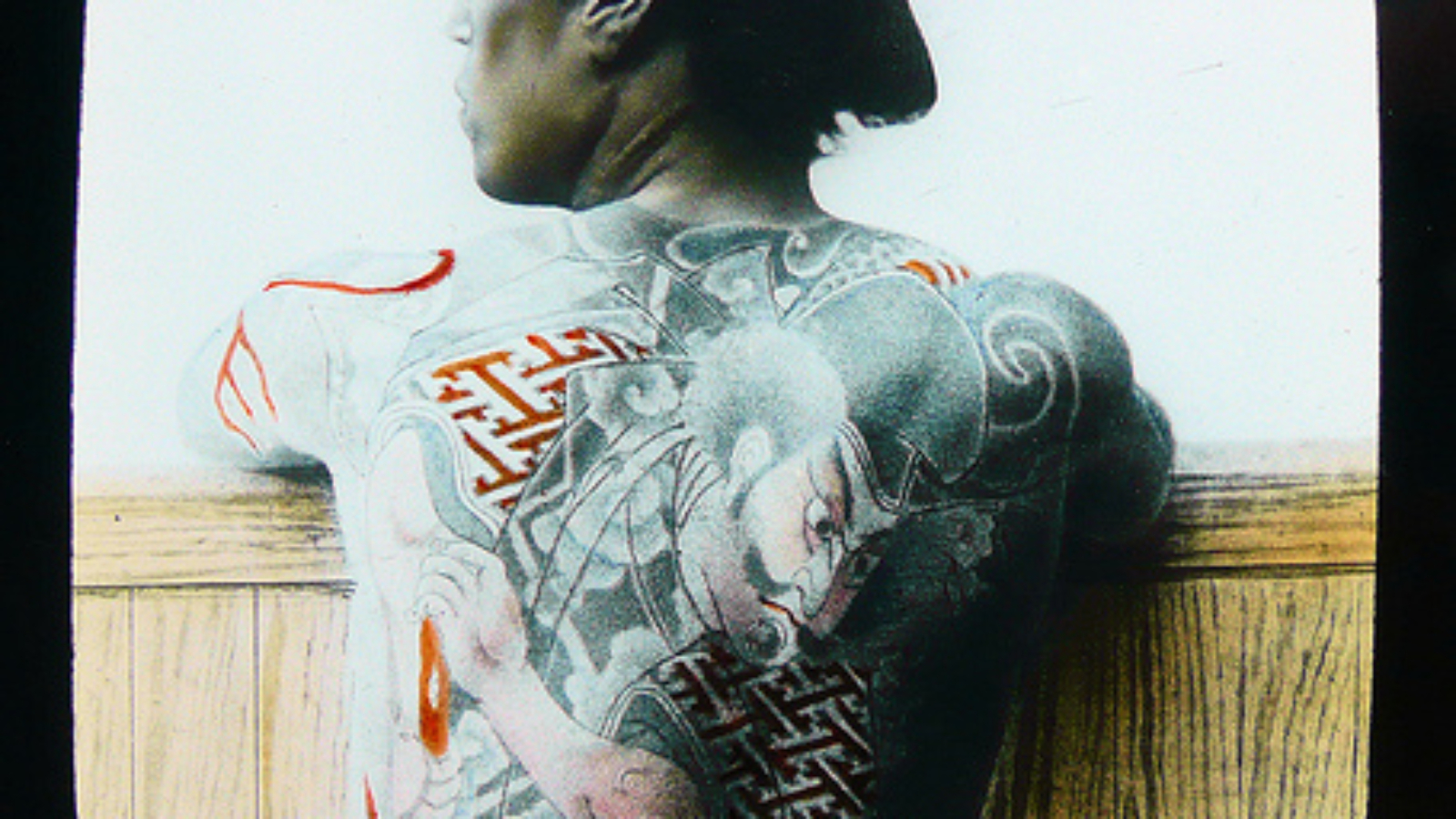

The yakuza have long-standing links with their country’s ruling parties. The Inagawakai, which still has their headquarters across from the Ritz-Carlton in midtown Tokyo, was a major power broker for many years and had former members elected as senators. For much of its history, even in the earliest days of the post-war era, the Inagawa-kai not only backed favored politicians, but produced them. Former Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi’s grandfather, a cabinet minister, was referred to by his constituents as irezumidaijin, or the “tattooed minister,” because of his affiliation with a yakuza group. Many top-ranking yakuza favor heavy tattoos that cover much of their bodies.

More recently, former LDP Senator Koichi Hamada was an Inagawa-kai member, according to police sources and organized crime members. Before his career in politics even began, in 1969, he maintained close ties with a number of organized crime players, including Kodama, the notorious power broker. Hamada is said to have been hand picked by the head of the Inagawa-kai to represent the group’s interests in the Diet.

Former Prime Minister Yoshio Mori was also notorious for his connections with the yakuza—so much so that he was accused by the media of being “married to the mob” after he admitted that, while in office, he attended a 1996 wedding reception for the son of a former yakuza group head. On December 11, 2000, the weekly magazine Shukan Gendai published photos of the then prime minister together with gang members at the event. Mori promptly tried (unsuccessfully) to sue the magazine, demanding nearly $400,000 for defamation.

The Turn

In 2007, the Yamaguchi-gumi felt its very survival was at stake. The shift of their support to the DPJ was a direct response to fears that a strong LDP electoral triumph would embolden its leaders to act against their interests. Tokyo governor Shintaro Ishihara had already led several waves of crackdowns on illegal sex businesses and gambling dens in the Shinjuku and Roppongi districts of Tokyo, cutting off the yakuzas’ shinogi, or revenue streams. With money low and laws that could further limit their activities on the horizon, it was time to make a dramatic change.

Yamaguchi-gumi members now admit that, in 2007, a DPJ leader made a deal with Takayama Kiyoshi, the acting head of the clan. Sources in law enforcement and the criminal underworld both assert that, by promising no new anti-organized crime laws, the two major yakuza groups actively pledged to support the DPJ. The yakuza would require their members to vote for candidates and contribute funds to the party— including corporate donations from front companies and individual contributions from their employees. Moreover, the clans would provide the DPJ with information that could embarrass political rivals and strong-arm any opposition party members who might attempt to damage the party’s reputation. The yakuza are media savvy. An NPA report on a Yamaguchi-gumi in Tokyo noted the particular attention the gang paid the press, including the “…intimidation of mass media. Using the organization name (and powers), members will seriously and relentlessly threaten whoever is responsible for unfavorable coverage. The leaders offer information to weekly publications (including thank-you payments to reporters).”

When Lehman Brothers Japan was defrauded of $350 million in 2008, police believed that the Yamaguchi-gumi provided some of the funding to make the deal work.

While the DPJ ’s recent success may be in no small part because of their yakuza backers, it comes at a price. After the 2007 elections, a DPJ Diet member from Saga prefecture, Hiroshi Ogushi, was spotted at the funeral of a murdered yakuza head. “I was asked to do it by a supporter and couldn’t refuse,” he said. “I never met the guy myself.” He resigned from his position soon after. The DPJ leader Ichiro Ozawa has also been tarnished by recent revelations of his ties to organized crime. In 2008, the Asahi Shimbun and other leading newspapers reported that, in 2005, the politician had used offices in a Fukuoka building belonging to a real estate agency run by the yakuza. Speculation has run rampant across the Japanese blogosphere as to whether Ozawa has direct yakuza connections. The most prevalent theory connects Ozawa through his mentor, Shin Kanemaru, who was well known for his ties to organized crime. A black cloud hangs over him, although no one is willing to go on the record and say that, indeed, Ozawa cut a deal with the Yamaguchi-gumi.

When asked for evidence of yakuza and DPJ collusion, police sources say the most damning evidence is the appointment of Shizuka Kamei. Kamei, the Minister of the Financial Services Agency (FSA) is charged with maintaining the integrity of the nation’s finance industry. But as an official in the NPA says, “With his past yakuza connections, the appointment of this man is a slap in the face to the government’s last three years of attempting to clean up the stock markets and keep the yakuza out of high finance. It’s the equivalent of putting a fox in charge of the hen house.”

The Fox

Shizuka Kamei was born in Shobara, Hiroshima, on November 1, 1936. His father, Soichi Kamei, was a farmer, while his older brother, Ikuo Kamei, later became an LDP legislator. The younger Kamei graduated from the prestigious Tokyo University with a degree in economics. During his college years, he studied Marx and Lenin, but never supported communism. After graduation, he worked as a laborer at a large Japanese chemical company. The anpo toso—the national movement opposing the U.S.-Japan security treaty in the early 1960s—led Kamei to a dramatic career change.

According to the newspaper Chugoku Shimbun, Kamei witnessed students protesting the anpo toso break through crowds of police and rush into the Diet building. He grew frustrated by the inaction of officers on the scene. He joined the National Police Agency in 1962 to “help contribute to public order,” rising through the ranks to the secretariat. In 1977, Kamei retired from the police force to enter politics, and was elected a senator on the LDP ticket 1979, rising rapidly and eventually forming his own faction within the party, which became known for its influence in the agriculture and construction industries. In 2005, Kamei left the LDP to form the People’s New Party.

During the whirlwind election of 2009, Kamei’s People’s New Party, together with the Social Democratic Party, formed a coalition with the victorious DPJ. A gifted multitasker, Kamei’s reward was to head the banking and postal services ministry in the current cabinet of Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama, as well as the Financial Services Agency. All the while, he remains the leader of the People’s New Party. He is unafraid to wield his power. Kamei’s magnum opus has been a bill known as “the moratorium.” Passed in the lower house of the Diet last November, the new law encourages banking and loan businesses to allow debtors to defer repayment on loans. At the same time, the FSA has been busy pressuring Japanese banks to be more lenient with the requirements for borrowers, and to provide loans for more small and medium-sized businesses. These may seem like benevolent measures for a depressed economy, but police sources allege that the major beneficiaries of these changes will be yakuza.

[The DPJ] don’t disapprove if their political appointees happen to have yakuza ties.

According to sources within the NPA and the Tokyo Metropolitan Police, as well as senior yakuza members, Kamei still has connections to organized crime. His associates include a number of corrupt individuals, including three Yamaguchi-gumi members— advisor Eichu Kyo, stock-speculator Ikeda Yasuji, and Kajiyama Susumu, also known as “the Emperor Loan Shark.” Kamei has also received funds from front companies run by the yakuza. The book Botochinjutsu, published by the Mainichi Newspaper in 1992, points out that Kamei has admitted receiving $5 million, paid into his own bank account from a yakuza front company. While Kamei has been connected to a number of political scandals in the past 20 years, he has never been criminally charged. Police sources speculate that his many years in the NPA have won him strong support within the police force and access to sources who leak details of investigations, making it nearly impossible for law enforcement to build a case against him. A long exposé of Kamei, written anonymously, noted that people too close to him have a habit of killing themselves, disappearing, or dying as soon as the authorities show any interest.

According to organized crime sources and law enforcement, the Kamei-backed moratorium bill will ultimately benefit organized crime more than anything else. Sources say Kamei was approached by the Yamaguchi-gumi via a right-wing political party, Nihon Kominto, and asked to implement the moratorium to save yakuza-related front companies, since many had lost huge amounts in real estate speculation when the bubble collapsed. They also hope to spur growth of debt collection agencies. Not coincidentally, the Yamaguchi-gumi are well invested in this field (their use of extra-legal tactics results in high rates of repayment).

The relaxation of inspection laws, coupled with Kamei’s ability to bring pressure on the financial oversight institutions he supervises, will make it even easier for yakuza groups to take out small business loans that become ripe for default. One police source notes, “A third or more of the loans made to small businesses through special programs are consumed by yakuza front companies, which don’t repay them. They take the money, trash the company, move the assets somewhere else and repeat the process. Lax checks on firms wishing to borrow make this very easy to do. By weakening checks and urging banks to loan more, it may be that Kamei is indirectly funneling money into the coffers of organized crime.” Changes in proper lending practices have started to bankrupt Japan’s consumer loan industry, and Kamei has been a vocal opponent of any attempts to save it. If the industry fails, there will be a surge in the use of loan sharks, according to the Japanese media and law enforcement. Once again, Kamei’s stance appears to benefit organized crime.

Who Let the Dogs Out?

If the DPJ has a strong aversion to organized crime, it’s not apparent. Shizuka Kamei’s appointment certainly suggests that, even if the DPJ does not overtly support the Yamaguchi-gumi or the Inagawa-kai, they don’t disapprove if their political appointees happen to have yakuza ties. With the dramatic turn in the 2007 elections—which replaced the half century rule of the LDP by the DPJ— it doesn’t seem as though the electorate cares much either. Criminal reform amid today’s economic turmoil seems far down the list of priorities for the nation’s voters. The yakuza, then, are well situated to control— even expand—their traditional activities for some time to come.

But the Yamaguchi-gumi and Inagawakai support of political parties is never a matter of loyalty. It’s always a question of what’s being done on their behalf. The DPJ kept its promise—there’s no criminal conspiracy law on the books. At the same time, police across Japan have been applying a wider interpretation to existing laws, arresting organized crime bosses for murders committed in gang wars and holding them liable for criminal activity conducted by their underlings—a new tactic in this conflict. The Yamaguchi-gumi is allegedly very unhappy with the DPJ’s failure to restrain its “dogs.”

In his autobiography, Tadamasa, the former head of the Goto-gumi, offered to testify in open session before the Diet on the dirty work he conducted as an organized crime boss for Sokka Gakkai and its political party, Komeito. The timing couldn’t be worse for the DPJ, which was on the verge of forming an alliance with Komeito to maintain a majority in the Diet. As the media began reporting on the book, Komeito found itself facing some serious public relations problems. Should DPJ popularity plummet, there is a looming possibility that they will have to form a coalition government, and what recently could have been a critical ally (the Komeito) is now receiving a public drubbing. Police officers who collect intelligence on organized crime say that the yakuza are sending the DPJ a clear message—do our bidding or you will be replaced. Just as we made you, we can unmake you.

The last DPJ-backed politician who was extremely vocal about the [yakuza] issue was the assassinated mayor of Nagasaki.

But now, more than ever before, the yakuza’s threats may be moot. In late May of this year, the National Police Agency summoned the heads of Japan’s three major crime groups to their offices for separate, clandestine meetings. Each of them was told the following (this comes from a source inside the NPA who wishes to remain unnamed): “Under the current administration, we may not be able to get a criminal conspiracy law on the books. But if you’ve been paying attention, we’re working with the Ministry of Justice to apply the existing ‘Laws on Punishment of Organized Crimes and Control of Criminal Proceeds’ in that fashion. That’s why your bosses are getting arrested for gangland murders along with the trigger men. Tell your executives that your days are numbered. Two, three years at most. Behave yourselves, avoid harming civilians, and maybe you’ll have a little more time. Either way, things aren’t going to go back to the way they were. You’ve been warned.”

In June of this year, Hatoyama resigned as prime minister, taking responsibility for his inability to keep his campaign promises about the American military presence in Okinawa. DPJ leader Ichiro Ozawa, believed to have been involved in many illegal activities, also announced he would resign, amid a scandal over his use of political funds. Kamei Shizuka resigned a week later, perhaps fearing public scrutiny, but made sure his successor was a political disciple who will do his bidding.

The new prime minister, Naoto Kan, is said to strongly oppose any back door deals with criminal elements. The day before his election, Kan said, “Ichiro Ozawa has invited the suspicions of the Japanese people. For his own sake, the sake of the party, and the sake of Japanese politics, it would be best for him to be quiet for a while.” On the other hand, Prime Minister Kan will need to tread carefully. He has yet to address Japan’s growing yakuza problem publicly. The last DPJ-backed politician who was extremely vocal about the issue was the assassinated mayor of Nagasaki. The nation’s new leader appears to have had nothing to do with brokering the deal between his party and the yakuza, but he will be expected to honor it.

Sarah Noorbakhsh contributed to this article.

Read about the scandals between sumo wrestling and the yakuza.

Watch Jake Adelstein on The Daily Show.

Top picture from Okinawa Soba via Flickr.

Graphs via wikimedia commons, public domain images.