This article originally appeared as Part VII in a series of articles on the history of the World Policy Institute leading up to World Policy Around the Table: A 50th Anniversary Celebration and Conversation.

By Amanda Dugan

Like a young boy on his bar mitzvah, the World Policy Institute reached a new level of maturity in its 13th year of existence. The year was 1974 and the World Policy Institute made headlines around the world with the report, “World Military and Social Expenditures.” Originally published as an annual report by the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency (ACDA), the World Military and Social Reports were discontinued in 1972. According to the then Secretary of Defense, Melvin Laird, these reports “contained misleading comparisons between military and social spending … complicating the Pentagon’s task of presenting the defense budget to Congress.” As a result of Secretary Laird’s concerns, any mentions of social needs were removed from the report. Also, with the ACDA restructuring and facing budget cuts, the staff in their economics bureau—the department responsible for the report—was dismissed, including the report’s author, Ruth Leger Sivard.

Despite these setbacks and the Pentagon’s attempt to bury the arms report, Sivard continued publishing her findings with the support of the Institute, along with the Arms Control Association (ACA) and the members of the Congress for Peace Through Law. And, while the ACDA stalled the release of its newly condensed and renamed, “World Military Expenditures and Arms Trade 1963-1973,” until January 1975, Sivard used her newly gained independence to provide the public with vital information about the social and economic consequences of the arms race.

In her own words, Sivard explained that the purpose of the report—comparing both social and military expenses—was to “bridge a gap in the information available to the public … [and] focus attention on the competition for resources,” encouraging the public to reassess their priorities. Similarly, Saul Mendlovitz, the Institute’s president, wrote in the foreword to the 1974 that in addition to filling this gap, the report was a “dismal reflection of our values as a world community that we have thought it necessary to invest so much more of our wealth in military power than in meeting the needs of society.” For its part, the ACDA explained that its decision to remove social expenditures was because “military spending retains a high priority in the budget of most nations.”

While the importance of arms spending within global budgets was confirmed by both reports, Sivard’s comparative context showed how the arms race was affecting developing nations that—although they were unable to provide basic services for their populations—were focusing the majority of their spending on military arms. In fact, military spending was increasing 5 percent every year in developing countries, compared to 1.4 percent in developed countries. Even more troubling, developing countries money on arms faster than they could make it. According to Sivard’s report, military spending increased 3.5 percent faster than these countries’ economic growth. Despite this statistic, the ACDA maintained that it would be “incorrect to assume” that developing nations were “putting strains on their economies by military spending.”

Regardless of the strain that military spending put on individual economies, the fact remained that by 1973 the world’s military spending was close to $300 billion. But, as the report made clear, it wasn’t just the diversion of financial resources that was a concern—there were as many soldiers per 10,000 population as teachers in developed nations; 25 percent of the world’s scientific talent worked on defense; and 40 percent of public and private research funding was devoted to defense. At the same time, while all of this money and talent was being channeled into arms development and defense, the United Nations spent only about $58 million annually for its conflict-prevention and peacekeeping operations, and this was the height of the “Disarmament Decade.”

As Saul put it, the report painted a “grim” picture of world values, and demonstrated how little progress the world had made toward creating a peaceful, cooperative system. At the same time though, the impact and resonance of the report was an encouraging sign of changing times. Newspapers in Japan and around Europe ran headlines covering the report, providing enough momentum to carry the report through its next few publications as Sivard and the Institute continued to expose the misappropriation of government funds on defense, in a world dealing with severe poverty and famine.

With all of this attention, the Institute’s message—the warning they had been giving for years—was impossible to ignore: Unless we changed the system, we would destroy it. As Douglas Dillon explained once, the Institute’s work was grounded in the belief that “the world should begin to make up its mind about fundamental changes in the near future, because otherwise we may not have very long before major catastrophes happen.” Now, with the Military and Social expenditures reports, the Institute had the quantitative backing to support these claims. According to George Kennan, in his foreword to the 1981 issue, “These volumes paint … the irrefutable statistical picture of the way in which our civilization is hurrying, in its anxious preoccupation with armed conflict, towards its own destruction.”

Realizing the importance of disarmament issues at the time, the Institute continued to develop in this direction under the new leadership of Robert Johansen. Launching two disarmament projects, Operation Turning Point and the Grenville Clark Project on Disarmament, the Institute started addressing policy issues at the source—through the politicians—while continuing its educational and grassroots efforts. And, with people such as Carl Sagan, Robert McNamara, and Robert Reich lending their names, the Institute was well positioned to make an impact.

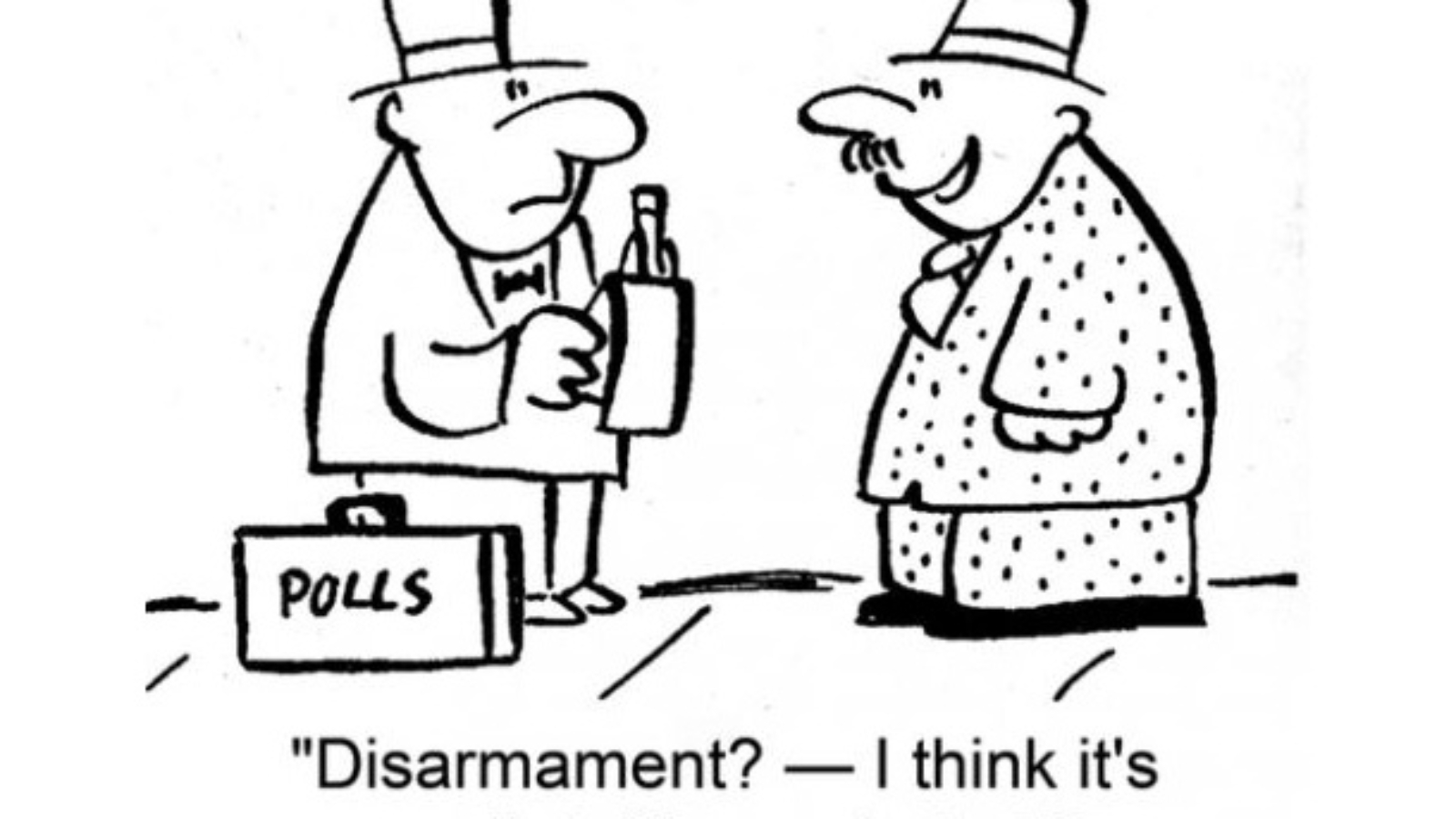

Setting out to provide new perspectives to the world’s problems, the Institute worked directly with Americans, launching a series of Greenberg polls to identify the American public’s real priorities. What they found was that—despite the prevailing policy assumptions—people were more concerned with economics, than with war. The willingness of the Institute to approach policy from a new platform set the stage for campaigns such as Clinton’s “It’s the economy, stupid,” and brought to light a shift in the American way of thinking. Rethinking security priorities in light of economic, social, and environmental concerns remains a cornerstone of the World Policy program, and as the Institute celebrates its 50th anniversary on May 3rd, we will continue to bring new perspectives and debates to the issues that affect all citizens.

****

****

Amanda Dugan is Director of Programs and Administration at World Policy Institute.

[Photo courtesty of Shutterstock]