From the Winter 2015/16 Issue “Latin America On Life Support?“

By Christopher Reeve

CARACAS, Venezuela—“This is the first time I feel like an emigrant,” says Evelyn, who calls herself a “free spirit,” and whose name has been changed out of fear of retaliation. She has left Venezuela twice before. Now she is waiting in her sister’s apartment to be summoned for her final interview at the U.S. Embassy in Caracas to receive an immigrant visa and leave her homeland a third and likely final time. “Before, I escaped,” the 62-year-old consultant says about her prior adieus. “Now I am emigrating.”

There is singing in the next room. On the other side of a closed door, a group of women in their early 20s break into song. “So that she may never leave!” they repeat, joining Marc Anthony. In the song, called “Flor Pálida,” Anthony tells the story of a flower he finds in poor condition and nurses to health. He promises to care for the flower so that it might stay with him forever. The women are partaking in a going-away party for two lifelong friends who are moving to Ecuador. The women sing, laugh, and recall good times—they don’t cry. They are used to these goodbye parties.

For the first time in its history, Venezuela is finding its place among other Latin American nations, where political, economic, and social conditions have thrust citizens abroad. Sixteen years ago, Hugo Chávez became president of Venezuela and put the country on a trajectory mired in controversy.

PRICE TAGS OF SOCIALISM

Chávez’s socialist agenda helped reduce infant mortality, but increasing violence has actually lowered life expectancy for men. Price controls were introduced to make basic goods like milk and Harina Pan, Venezuela’s most popular brand of corn flour used to make arepas, accessible to the country’s most vulnerable citizens. But the price controls have led to widespread shortages, ballooning inflation, a thriving black market for hard-to-access goods like toilet paper, shampoo, and diapers, and at supermarkets, looting, fighting, and lines that span blocks. Producers of goods face insolvency as the cost of inputs purchased at black market rates easily exceed government-mandated prices for final products. Expropriations have decreased efficiency and productivity. Three legal and one illegal exchange rates feed speculative trading and gaming of the monetary system. Depending on which rate you apply, a basic lunch might cost over $100 and a domestic flight less than $7. The chaos that is Venezuela’s economy is currently a vicious cycle that feeds on the lack of confidence it creates.

The “food basket,” a tool used to determine how much the average Venezuelan household needs to spend on the minimum amount of monthly food, is currently at over 78,000 bolivares (or $12,284). The minimum wage is just under 7,500 bolivares ($1,181). Venezuelan homes need over 10 minimum wages to be able to afford the baseline nutritional intake. It doesn’t matter though. Venezuelans can spend several weeks trying to find milk and rice unsuccessfully. Bottled water is more difficult to come by than cola, and supermarket meat sections are empty. Food is only the beginning. Goods like car parts, pet kibble, prescription medicine, and over-the-counter painkillers require time, money, and, increasingly, connections to acquire.

The government blames conditions on an “economic war” brought on by Venezuela’s escuálidos, people who oppose the country’s ruling Socialist Party, and the Colombians in Cúcuta, who, with exiled Venezuelans in Miami, determine and publish the black market bolivar-dollar exchange rate. “This bourgeoisie that has dared to sequester the economy will be sorry in the future for having caused the pain and suffering of the people,” Venezuela’s current president, Nicolás Maduro, announced at this year’s Independence Day celebration in Caracas. “Long live the legacy of Hugo Chávez!”

“Viva!” onlookers responded.

The government accuses low-level traders, believed by many to be Colombians who buy products at prices well below their market value in order to resell them at a profit, a process called bachaqueo, for conditions in Venezuela.

The scapegoating of Colombians for Venezuela’s economic woes came to a head in late August. The Venezuelan government began cleansing border areas of Colombians. Security officials pulled Colombians from their homes in towns like San Antonio de Táchira and put them on buses to Colombia. Over 1,000 Colombians were deported. Thousands more, fearing increasing xenophobia, left voluntarily. Border crossings were closed. Meanwhile, a car ride from Maracaibo in Venezuela’s western Zulia state to the Colombian border town of Maicao reveals Venezuelans, not just Colombians, continuing to move underpriced goods from Venezuela to free markets in Colombia.

The irony is that when it was politically expedient to welcome and nationalize thousands of Colombians that is exactly what Chávez did. With Venezuela no longer riding the wave of relatively high oil prices of the 2000s, any notions of the country as a socialist utopia open to the poor and down-trodden of other lands are all but dead. And the government does not admit to making mistakes.

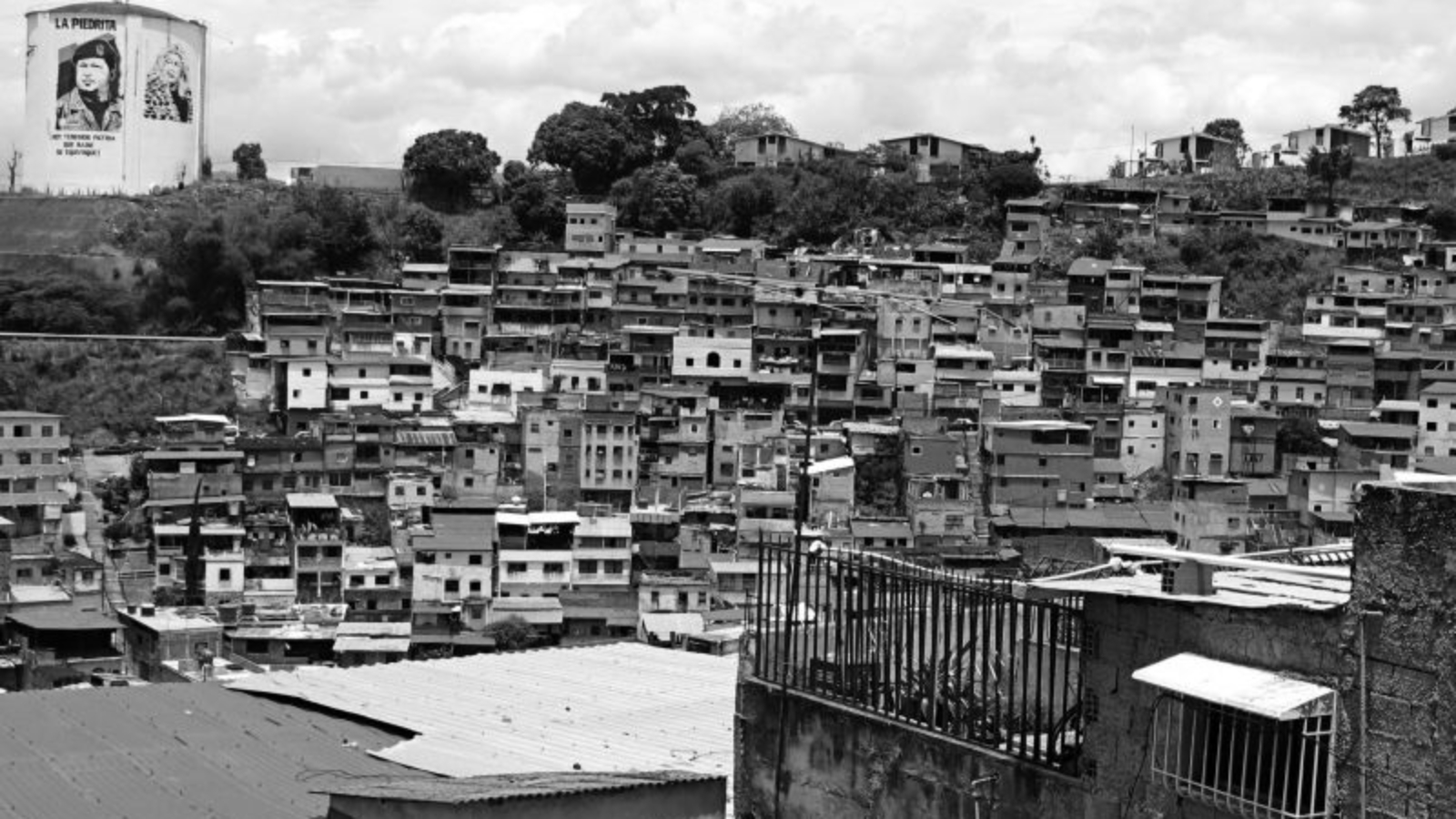

MASKING REALIDAD

Venezuela’s capital, Caracas, tucked in a horizontal valley, enjoys a year-round cool climate and green, cloudy mountain scenery. The city’s beauty masks a violent reality.

Four years ago, Evelyn’s son Nelson, whose name has also been changed per request, was in his car in front of his apartment building in Caracas one evening. Two men with guns cocked approached both sides of the vehicle, pointed their weapons at him, and demanded the car and Nelson’s cell phone. Nelson gave the men the least expensive of three phones he kept for such occasions, a popular strategy in Venezuela, a country with rampant crime and recognized as having the second highest homicide rate in the world. Caracas, with a homicide rate of 116 per 100,000 inhabitants, is the second most violent city in the world, according to the Citizen Council for Public Safety and Criminal Justice, a Mexican civil society organization. The Venezuelan cities of Valencia, Ciudad Guayana, and Barquisimeto also make the group’s list.

Nelson, now 32, obliged because he knew Venezuelans are killed for less. The armed robbery was the beginning of a period when Nelson began seriously to consider leaving a Venezuela that was increasingly dangerous, polarized, and foreign to many of its citizens. Weeks after the car robbery, a man on a motorcycle tried to rob Nelson, who escaped by running into a shopping center. For Nelson, Venezuela had passed the point where strategizing to stay safe consumes the mind. He recalls that a partner at his construction firm had been kidnapped, as had another partner’s daughter. The danger was getting too close for comfort. Friends and colleagues were already leaving the country. “That’s when I decide, ‘You know what? This country’s going to hell,’” he says. He gave his boss one month’s notice before his departure.

The car robbery her son experienced was also the tipping point for Evelyn. She knows he could have easily been killed. Decades ago, Evelyn had difficulty getting pregnant, and once Nelson was conceived, she experienced a high-risk pregnancy. She wasn’t going to lose her only son to the Wild West that Venezuela had become. Nelson was born in Miami. About his mother’s desire to have her only child in the United States, he says, “I thank her every time I can, because it opened up a lot of possibilities for my future.” U.S. citizenship was Nelson’s ticket out of Venezuela.

Nelson left the country for Miami. Evelyn left the capital for Maracaibo, some eight and half hours from Caracas, near the Colombian border. It is here in Venezuela’s second city, with its flat landscape, low-rise buildings, and distinctly Caribbean feel, that Evelyn awaits her departure from the country.

Hours before we spoke in her sister’s small kitchen, Evelyn had gone to buy snow cones at her favorite spot. The owner’s children now run the small stand. Their father was killed for not paying the vacuna, a “tax” bandits levy on businesses for “protection.” While Evelyn sought snow cones, her nephew, with other family members in the car, hit the gas and made an abrupt left turn when he saw a motorcycle with three men coming at him. One of the men pulled something out of his pants and pointed it in the direction of the car. Whether the men were malandros, thugs, or not, in Venezuela you don’t stick around to find out. Paranoia, especially regarding men on motorcycles, is endemic.

Venezuela’s socialist leaders don’t recognize the ills of their oil-rich country. In 2012, Univision’s Jorge Ramos asked Diosdado Cabello, the speaker of Venezuela’s National Assembly who is also accused of drug trafficking, about the country’s high level of violence. “Part of the international war against Venezuela is what you are saying,” Cabello responded. He then alluded to the idea that Ramos was working with the U.S. government to help the latter gain control of Venezuela’s natural resources.

VENEZUELANS WANT OUT

There is also scant public recognition that Venezuelans want out. Six percent of Venezuelans, or two million, have already left, and 10 percent are in the process of leaving, according to several surveys. Another study finds that nearly half of Venezuelans (49 percent) would leave Venezuela if they could. In the United States alone, the population of Venezuelan-born jumped from 49,000 in 1990, nine years before Chávez came to power, to 248,000 in 2013.

Last summer, Maduro blamed right-wing elements for spreading the lie that Venezuela’s youth want to leave their country. “The youth of this country love Venezuela,” he said, “and want to create a homeland.” The reality, though, is that 65 percent of Venezuela’s youth want to emigrate. Venezuela’s vice president, Jorge Arreaza, said that more than a brain drain, the country was experiencing a “brain robbery,” implying a conspiracy to steal the country’s talent. Arreaza’s recognition that Venezuelans are leaving is rare. Official voices generally decry figures, rankings, and reports that cast a shadow on their socialist experiment as exaggerations and conspiracies.

Violent crime, economic malaise, loss of hope, and emigration are recurrent topics of conversation in Venezuela. Statistics about desire to emigrate and perceptions of Venezuela’s state of affairs come from surveys. The government does not appear to analyze airport migration forms to access hard data on emigration patterns. If it does, conclusions are not made public. The Mexican organization that listed Caracas as the second most violent city in the world says Venezuelan data is hard to come by, noting that the nation’s “leaders, instead of transparency and accountability, prefer concealment or propaganda, frequently based on lies.”

The first two times Evelyn left Venezuela, she was happy—but not now. She leaves family behind, and it will be difficult for them to qualify for visas to the United States. “Now I’m saying goodbye to Venezuela. It feels very different,” she says. “There is pain.” In 2013, Nelson started petitioning the U.S.’s Department of Homeland Security to give his mother residency. For a filing fee of $420, U.S. citizens at least 21 years of age can do the same for their non-U.S. citizen parents. Not all requests are granted. From the beginning of 2015 until late October, 2,348 Venezuelans were granted immigrant visas. Venezuelans receiving non-immigrant visas to the U.S. during the same period number 237,924. Many within this category, once in the U.S., will remain. The U.S. State Department, which grants the visas, does not provide data on total requests for either category.

Back in Caracas, Carmen, (who also asks to conceal her name out of fear), 25, has struggled with the decision to leave Venezuela. “I wouldn’t go to another country to feel like a foreigner unless I’ve come to feel like a foreigner in my own country,” she says one afternoon in a café in the high-class Altamira district. “I now feel like a foreigner in this country.” Carmen, who works in finance, was wrestling with how to leave Venezuela. She just knows she wants out. She is investigating new Spanish legislation that welcomes descendants of Sephardic Jews to the Iberian State that expelled them in the 15th century. Carmen is now researching her surnames to see if any of them could grant her a ticket to Madrid.

She reflects on some of the major reasons Venezuelans offer for emigrating: desire for personal and professional development (44 percent); insecurity (21 percent); and poor economic conditions (20 percent), according to a recent study by DatinCorp, one of a handful of firms that sheds light on Venezuelans’ perceptions of their country. Carmen says she can’t choose any single reason over any others. She eventually decides on her major reason for wanting to leave. “I find it difficult to stay in a country where the government constantly makes you the enemy.” When Maduro echoes Chávez and calls the enemies of the people, “oligarchs,” “burghers,” and “squalid,” he refers to people like Carmen, who, at least until recently, have led relatively comfortable lives.

On a recent trip to New York, Carmen recalls sitting in a plaza in midtown Manhattan. She didn’t feel the need to constantly assess the safety of her surroundings. She didn’t feel the ever-present fear of being robbed. “That tranquility is invaluable,” she says. “If you don’t live in Caracas, you don’t appreciate it.” Carmen’s brother was kidnapped and eventually released. Kidnapping for ransom is increasingly common in Venezuela.

“In Caracas, there isn’t a single area where I feel safe,” Carmen says. Another recent DatinCorp report says that nearly 60 percent of Venezuelan families have been victims of crime in the last year. Carmen says that Venezuela’s crime and violence have translated into a loss of freedom for Venezuelans, as many don’t go out at night anymore, choosing instead to lock themselves in their homes at sunset.

Two weeks after Carmen and I spoke, she messaged me to say that she had been offered a scholarship to earn a graduate degree in the United Kingdom. Venezuela’s Central Bank used to sell dollars to Venezuelans like Carmen at a rate of 6.30 bolivares, well below today’s 730 bolivares market value, as published by Miami-based dolartoday.com. Carmen, who says half of her family and friends have already left Venezuela, knows students who did not receive dollars they bought from the Venezuelan government. In April of this year, Tarek William Saab, Venezuela’s ombudsman, announced that 60 percent of Venezuelan students who had left the country for post-graduate studies had not returned, which, along with decreasing reserves, is a reason Venezuela’s central bankers would stop selling cheap dollars to Venezuelan students going abroad.

As a stipulation for receiving the scholarship, Carmen agreed to return to Venezuela after her studies. Like the 60 percent of her peers who defected, though, she has no plans to do so. With the start of fall, Carmen began her first semester as a master’s candidate at the English university that agreed to accept her. Nelson, in Miami, has a law degree. They both have education levels that are reflective of most Venezuelans abroad. Ninety percent of those who have left Venezuela have at least one post-secondary degree. A Pew Center analysis of Hispanics of Venezuelan origin (foreign and U.S.-born) in the United States found that that community has higher education levels than the U.S. population as a whole. Half of Venezuelans 25 and older have at least a bachelor’s degree, compared with 29 percent of the U.S. population.

AT HOME IN DADE

Some 41 percent of Venezuelans in the United States are in Florida. Tomás Páez, a sociologist at the Central University of Venezuela and author of La Voz de la Diáspora Venezolana (The Voice of the Venezuelan Diaspora), estimates Miami is home to 120,000 to 130,000 Venezuelans. “Miami te espera,”

“Miami awaits you,” declares a billboard alongside a highway in Caracas, beckoning would-be émigrés. The ad is for housing in the city of Doral in Miami-Dade County. Miami, like it was for Cubans, has become the capital of the Venezuelan exile community. Doral, now affectionately called Doralzuela, has become the center for social and political gatherings for Venezuelans opposed to the ruling regime 1,300 miles away.

José Colina, 41, is president of Politically Persecuted Venezuelans in Exile (VEPPEX). Colina’s race, humble origins, military background, public fallout with Venezuela’s “officialists,” and the fact that men like Diosdado Cabello of Venezuela’s National Assembly, regularly single him out as “the fugitive,” give credibility and are perceived as badges of honor by Venezuelan exiles looking for a leader in their fight against the Maduro government.

Based on asylum requests, Colina estimates that there are between 40,000 and 50,000 Venezuelans in the United States whose migration was the result of political persecution. Colina himself arrived in the United States 12 years ago. In 2002, Colina, a former lieutenant in Venezuela’s National Guard, was involved in a military takeover of Altamira’s France Square to demand that Chávez relinquish power. After eight months in hiding in Venezuela, followed by a month in Colombia, Colina, who had an American visa as he had studied there, boarded a flight to Miami.

“I made the decision to travel to the only country in the world where I would have the opportunity to prove my innocence and safeguard my life that was in danger.” After nearly two and a half years in various U.S. detention centers, petitioning for political asylum while Venezuela sought extradition, Colina became a free man in April 2006. “My life as a political exile started.”

Two years later, he founded VEPPEX. “Although the organization was born as a support and assistance platform for those who came as a result of political persecution, it became an organization of resistance, denunciation, and confrontation against the regime of Hugo Chávez and now Nicolás Maduro,” Colina says.

And VEPPEX is growing in size and reach. VEPPEX has 565 guayabera-wearing members in Miami alone, and another 12,000 members worldwide, Colina says. He adds that he has personally advised about 1,200 Venezuelans who sought political asylum. Other VEPPEX members have helped even more. Behind El Arepazo, a local restaurant, is a replica of a graveyard with 45 white crosses driven into the ground. On each cross is the name of a Venezuelan who was killed during the 2014 protests against the government. At a corner of the graveyard stands a statue of Simón Bolívar, the Venezuelan liberator and namesake of Chávez’s Bolivarian Revolution. Erecting the statue was, for Colina, also an accomplishment, a sort of visual marker that made the place “the heart of the Venezuelan exile community,” He further explains, “we didn’t leave to suck our thumbs or to be depressed while outside of the country. We left to fight, to continue the struggle that brought us outside of the country.”

While Colina lives in Doral, Nelson lives alone in a quiet development in the westernmost part of Hialeah, a city that is 95 percent Hispanic, largely Cuban and Cuban American. He keeps up with Venezuelan news, but is not an activist. He divided his childhood between Miami and Caracas, and recalls being happier in Caracas before Chávez’s policies and rhetoric changed everything for him. With Venezuelan colleagues, he cofounded a business in Doral. The firm has a steady clientele of Venezuelans, some newly arrived. But living in debt and feeling somewhat lonely, Nelson is not living the life he expected. “If I’m happy or not? I don’t think I’m very happy right now.” Since moving to Miami in 2011, he has gone to Venezuela seven times, the last nearly two years ago.

Now Nelson is focused on getting his mother out. Last summer, he had the chance to send her anything she wanted. She asked for toilet paper. But it’s not the shortages of basic goods that worries Nelson. “Mainly it’s her safety,” he says.

Another exile leader, Elio Aponte, 54, is living in hiding somewhere north of Miami, Florida. He is the founder of ORVEX, or Organization of Venezuelans in Exile. ORVEX, founded in 2005, helps Venezuelans record their tales of persecution and apply for political asylum. Aponte’s organization helps the “many undocumented Venezuelans in the shadows.” He puts the figure of such persons at 100,000. Aponte has spoken out against the ruling “officialist” party in Venezuela. In 2007, Aponte recounts, an announcer on Venezuelan state TV said that he was wanted for conspiracy. Aponte’s political asylum request was granted in 2010.

The Venezuelan government, Aponte says, has a list of the people who signed the referendum call against Chávez in 2003, and that the list is used to identify and intimidate. Aponte has called on Washington to refrain from deporting Venezuelans he says have been identified by the Maduro regime. Venezuela has various armed groups of official and semi-official status. He tells the story of one man whose political asylum request was rejected. Members of colectivos, armed groups of men affiliated with the ruling socialist party, told the man they were waiting for him in Venezuela. He went to Canada.

TARGETS

About 25,000 people are killed in Venezuela each year. Aponte says many of those homicides are politically motivated. With a dysfunctional criminal justice system and a stunning rate of 98 percent impunity, according to a government report, getting to the bottom of motives is nearly impossible. Many Venezuelans in the United States and Venezuela, adamantly requesting to withhold their names, have a real fear of violent, politically motivated reprisals.

Páez, the Central University of Venezuela sociologist, is currently in Spain with his wife and two daughters. His interest in the 2 million Venezuelans outside Venezuela is new. Páez used to focus on matters of business and entrepreneurship. That changed when one day he saw a pizzeria in Madrid with a name he recognized as having been established in Venezuela by an Italian immigrant family. He did some investigating. It turned out that the family had indeed left Venezuela for Spain.

In 2002, managers and workers at state-owned oil company Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA) went on strike. Oil production stopped for two months, and for their insubordination, some 19,000 employees were fired. A litmus test was established for anyone who wanted to work at PDVSA. You had to be on board with Chávez’s Bolivarian Revolution. In 2006, Chávez made his expectations clear: “The workers of Petróleos de Venezuela are with this revolution, and whoever isn’t should leave. Go to Miami or wherever.”

The son of the Italian family, a former PDVSA employee, left for Spain, as did his three sisters, one of whom was Páez’s sociology student. In Spain, Páez found 40 of his sociology students. He told himself, “This must be studied.” He ultimately conducted some 100 interviews and administered about 900 surveys among Venezuelans in 41 countries. It is Páez who came up with 90 percent as the figure for Venezuelans abroad with post-secondary degrees.

Páez rejects the notion that in order to contribute to Venezuela one must be inside the country. “They don’t even have to go back,” he says of emigrants. “They can contribute from afar.” He mentions Cuba, a country whose development model Chávez and Maduro have tried to emulate. “Cuba is going to experience a quantum leap with the support of those abroad. Those who left are going to save Cuba from the terror in which it finds itself.”

STAYING ON

The Andrés Bello Catholic University (UCAB) is 10 subway stations away from Plaza Venezuela in the center of Caracas. The subway system, over three decades old, is prone to delays or worse. On one trip to the university, the train stopped working several stations from Antímano, which is steps from the university. At a taxi stand, a man with a clipboard asks the destination. He looks onto a price list and states the fare. All passengers must open their bags. He peers inside and waves a hand-held metal detector over and around the bag, then does the same for each passenger. “It’s inconvenient, but for the greater good,” he says, “for all of us.”

Past security and on the other side of a pedestrian walkway over the Francisco Fajardo Highway, UCAB’s graduating students drink Polar beer and dance closely to the Pitbull-Osmani Garcia reggaeton hit “Taxi.” They let loose and enjoy their impending graduation at the outdoor fete. From the university, students have a view of the multicolored homes of the Antímano barrio, an informal settlement that climbs the hillside behind the subway station. In such barrios, the city’s poorest residents live and Chávez and his populist, socialist plan for Venezuela found their most ardent supporters. Today, the residents of such settlements face the same scarcity, inflation, and violence as their compatriots of greater means, but with fewer resources to deal with them. “You don’t go out because of the people of poor conduct,” says a 34-year-old woman from Petare, the largest barrio in Venezuela, about the malandros in her neighborhood. Like Venezuelans of other social strata, the woman says that she and her three children do not wear or expose anything that might be perceived as valuable. “No one wants to have anything. You don’t want to have something that will be taken from you,” she says. “The guys in the neighborhood are on watch to take cell phones.” The woman, born in Colombia, says she would leave Venezuela if not for the fact that her youngest child (and the girl’s father) is Venezuelan, which makes taking the girl to Colombia impossible at the moment.

Most students at UCAB come from a more privileged world. Many have bodyguards and travel in armored cars—at least until they can get out of Venezuela.

While many UCABistas say they hope to leave, others are adamant about staying and contributing their skills to improve conditions in Venezuela. After the music and beer celebration, a group of pedagogy majors, all wearing the same royal blue button-down shirt, settled down at UCAB’s food court.

Edward Izturriaga, 22, has no desire to leave. “I won’t leave unless I believe that with my life I’ve done something worthwhile,” he says. “And it’s not about my country per se. It’s about my life’s duty.” Izturriaga is tall with dark curly hair. “I want to feel the need, the actual privilege of having contributed something.” He measures his words before speaking. “May my life not be a statistic, like ‘300 Venezuelans were killed as a result of crime.’” Izturriaga has done all types of work, including acting as a street salesman. He now does small business consulting. He wants to develop soccer as a focus of a new brand of schools. The use of sports to engage young people is already proving effective.

In Caracas’s Sucre Municipality, politician Brian Fincheltub runs the 40-year-old Sucre Sports program for low-income youth. Fincheltub, a member of the opposition party Justice First, doesn’t sugarcoat the program’s major goal—“to lower the homicide rate.” Fincheltub meets a visitor at the two-year-old El Dorado Vertical Gym, a seven-floor structure built over a parking garage at the foot of Petare. At the gym—the largest in the country—Sucre’s young men and women can practice sports from boxing to basketball at no cost. There are even activities for persons with disabilities. Fincheltub says the mayor of Sucre Municipality, Carlos Ocariz, also of Justice First, has been able to lower Petare’s homicide rate by 45 percent.

Some 300 young Venezuelans from across the country gather for the finale of Future Now’s Lead 7 program. The young men and women, comprising 27 teams, have just finished a series of team-building activities that connect them with community members of Sucre, like taking the metro cable from the easternmost end of Caracas’s main subway line to Mariche, well above the city. They sit in the bleachers and on part of the outdoor basketball court of the Vertical Gym, with the colorful homes of the El Dorado barrio beginning to stack up just behind the court’s northern boundary. Andres Schloeter, a councilman in Sucre, asks the would-be leaders if they know people who have left Venezuela. Nearly everyone raises a hand. “May Venezuela be a welcoming country as it once was,” he says to applause. “A country of hope.”

The program’s participants are dedicated to staying in Venezuela and contributing their skills and knowledge to turning things around in a resource-rich country. Near the Vertical Gym’s boxing ring and through the cheerful chit-chat of their peers, a group of Lead 7 young men and women talk about staying in Venezuela. “I’ve thought of leaving, and I’ve thought of it many times,” says Pedro Rojas, a 25-year-old mechanical engineering graduate from Simón Bolívar University. “But I stay here because all of the unsatisfied needs to so many problems represent an opportunity.”

Gerardo Venegas, 27 and an industrial engineer graduate at UCAB, says, “Here, entrepreneurship is very easy compared to other countries. I think that we should take those opportunities. More than 1.5 million Venezuelan professionals have left, and the situation stays the same. Leaving is definitely not a solution to the issues we face here.”

FREE & FAIR?

Parliamentary elections are scheduled for early December, and, if free and fair elections are held and their results upheld, the ruling socialist party seems poised to begin its decline in Venezuela. But even if Parliament finds itself suddenly dominated by opposition parties, turning around the economic and social ills the country faces daily will take time. Perhaps it is that tough road ahead that feeds continued interest in leaving the country. Esther Bermudez is director of the popular website mequieroir.com. Typing the English-language equivalent, iwanttoleave.com, will also take people to Bermudez’s page with guidance for would-be Venezuelan émigrés. There is even information on traveling with pets. Bermudez says that traffic to her site has remained stable throughout 2015, with 180,000 page views a day, or over 5.5 million a month.

“We can affirm that the middle and upper classes in Venezuela have learned to emigrate. It’s already something that is normal and routine. We believe that it is an irreversible tendency,” she says. “Every year, countries like Australia and Canada receive thousands of residency visa requests from Venezuelans. Every Venezuelan has a friend or family member abroad.”

Although Venezuela has, at least in recent memory, always had social ills like crime and poverty, the country was an attractive destination for migrants from across Latin America, the Caribbean, and beyond. Caracas became home to Portuguese, German, Lebanese, Chinese, Romanian, Peruvian, and Brazilian migrants, among others. Venezuela’s reversal from a country that attracts outsiders to one that repels its citizens is not lost on observers. While the country is no longer the regional golden child, Venezuela still lags behind other Latin American states that have greater portions of their citizens abroad. Mexico and Colombia, countries with high levels of violence like Venezuela, have about 10 percent of their populations abroad. And compared to Venezuela, both countries have higher percentages of their populations receiving immigrant visas from the United States, the major destination for emigrants. There are even more extreme cases. There are currently 4.9 million Puerto Ricans outside of Puerto Rico, a U.S. commonwealth, compared to the 3.5 million on the island.

Without requiring U.S. visas, Puerto Ricans are moving to Florida en masse. As the region looks ahead, further migration might be jolted by decreasing global demand for and price of commodities, like copper and oil. For now, many Venezuelans are content to leave behind the Bolivarian Revolution for places like Panama and Colombia.

Nelson, in Miami, just received notice that his mother was approved for an immigrant visa. Once in the U.S., she will work on getting her green card, so she can stay permanently. “I’m happy!” he says.

*****

*****

Christopher Reeve is a writer and consultant specializing in Latin America.

[Photos courtesy of Christopher Reeve]