This article is part of the Digital Freedom and Control Project produced exclusively for the World Policy Journal by students from the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.

By Anna Edgerton

El Salvador is no stranger to bad news. A brutal civil war terrorized the country for 12 years and left a legacy of polarized politics and armed groups that were ripe for the transition to criminal gangs. El Salvador has one the highest murder rates in the world—a sad reality that makes tragic news commonplace.

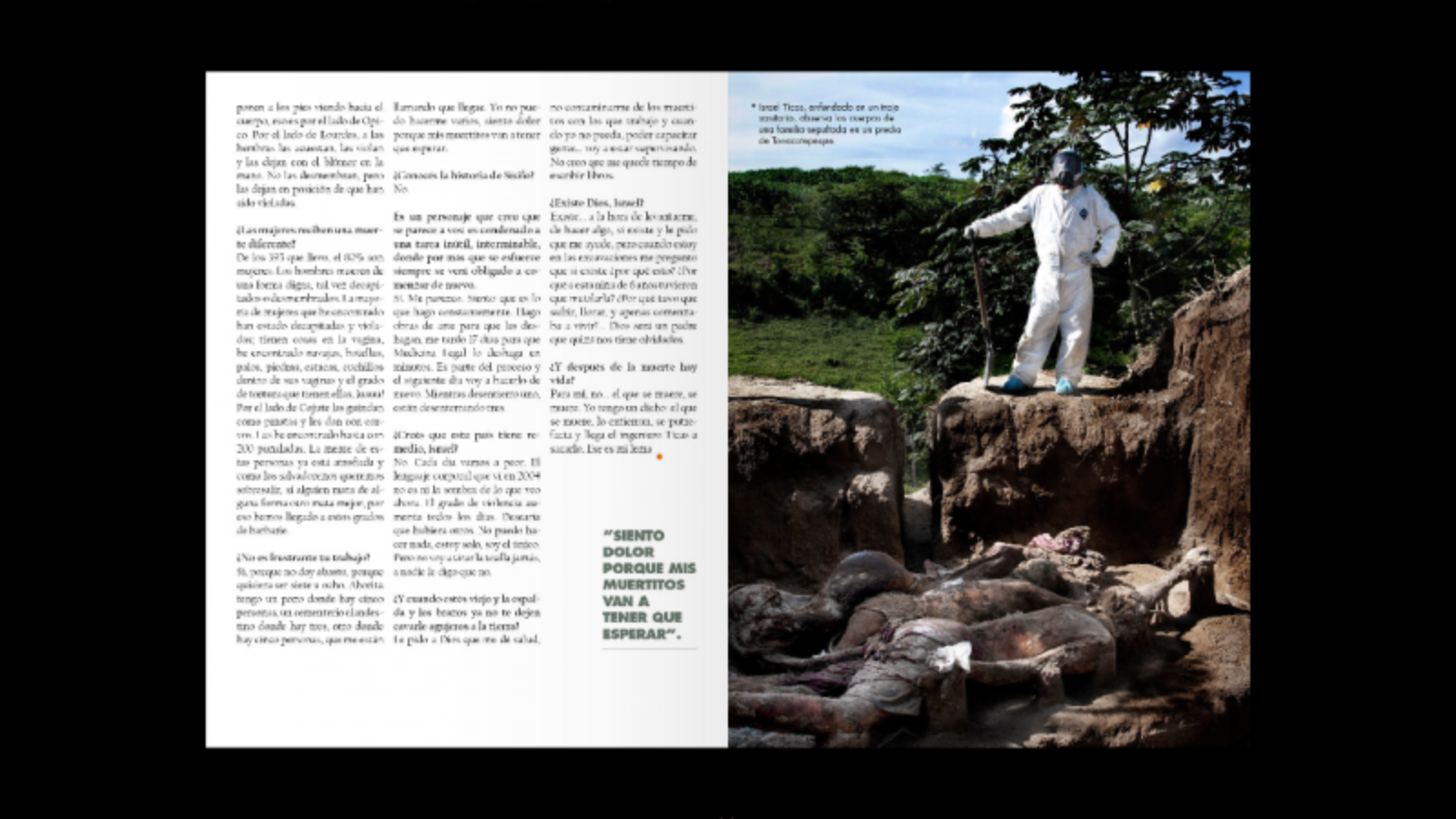

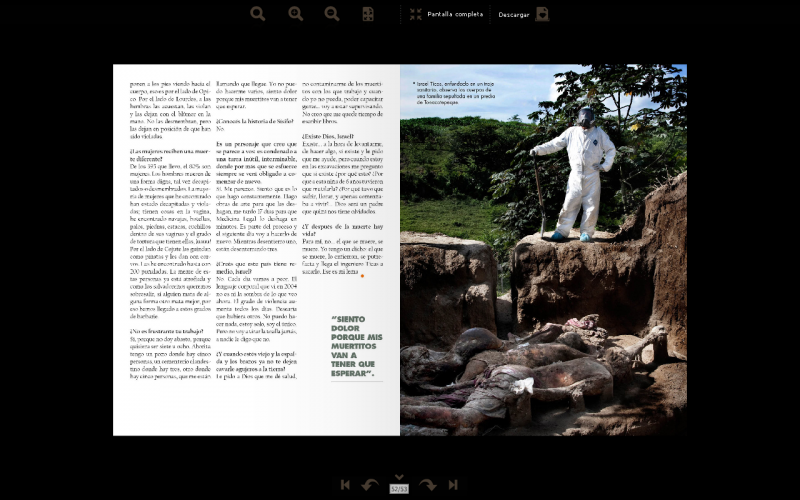

One award-winning magazine piece shows a different side of these alarming statistics. El Criminalista del pais de las ultimas cosas, chronicles the story of Isaac Ticas, El Salvador’s only criminalista, or forensic anthropologist. His passion is death, and his job is to dig up the half-decomposed bodies of those who have fallen victim to gang violence. Two journalists follow him as he does his grisly work and use his story to illustrate the heartache behind the homicide. The writing is graceful and intimate, and turning the pages reveals pictures of a remarkably beautiful countryside, followed by images of decomposing bodies and photographs of decapitated heads.

This disturbing story is not documented on paper, however, but in pages that must be turned with the click of a mouse. The project, at over 12,000 words, can only be found online, in the form of a revista digital (a digital magazine, pictured above) in four chapters, laid out with pictures and a corresponding video.

The report was published in a newspaper that has never been printed on paper: El Faro, Central America’s first online-only newspaper, begun by Carlos Dada and Jorge Siman in 1998, even before some established publications began to build their own websites. El Salvador’s 12-year civil war officially ended in 1992, and Dada said that the country’s media left much to be desired by way of independence and in-depth investigation.

“We both felt, especially after the peace accords, that a lot of exiles were coming back. Those people, intellectuals, artists, progressive businessmen, etc., were a very attractive public that would feel disrespected by a mass media designed to drive an agenda and talk to the public in a very basic way," Dada said. "We thought Salvadorans deserved more sophisticated media.”

Dada explained that they began their operation online, because they didn’t have the resources to start a print operation. Putting content online was supposed to be a temporary arrangement while they gathered the momentum needed to launch a newspaper. Somewhere along the way, the digital part of the periódico digital became the distinction that the operation needed to establish itself initially in the field of Latin American journalism.

Since it has always existed only online, the newspaper began with nothing: no costs of operation, no salaries for its founders or the novice journalists who signed up to learn the craft under Dada. And no revenue. This gave the publication the freedom to “say things no one else is saying, uncomfortable things for powerful people,” Dada said.

The country of El Salvador could be seen as an unlikely place to begin an online newspaper. The country is small, with a population of around 7 million people. Only 16 percent of people have regular access to the Internet. Yet this fraction of the population is precisely the target audience of El Faro: “the decision makers and the opinion leaders and the middle class youth,” according to Dada. “It’s the perfect public if one aims to spark real changes,” he said.

It’s difficult to pin down how many people in El Salvador actually read El Faro. The publication itself reports its traffic in static figures on the website: more than 300,000 readers and more than 950,000 page views a month. These numbers were based on the traffic to the website in March 2010. More recent metrics were not available.

El Faro, which in Spanish means “the lighthouse,” stands out in Latin America for its pioneering work in online journalism. Last month the publication won the Ortega y Gasset award from the Spanish newspaper El Pais for El Criminalista as the best multimedia project of 2010. The award recognizes excellence in journalism that contributes to “the defense of freedom, independence, rigor and honesty as essential virtues of journalism,” according to El Pais.

“It’s curious to have a country as small as El Salvador, to have a newspaper as small as El Faro—maybe 20 journalists—but we have a lot of international recognition,” said Bernat Camps, the photographer who worked on El Criminalista.

Dada said he appreciates the awards as “a vehicle to get more visibility among certain circles.” However, he pointed out that a lot of good stories have not received the same recognition as some other stories that were not as strong. For the awards that his publication has received, he explained that as "the definitive judges of the quality of a piece of journalism, they mean nothing.”

One of El Faro’s most important stories was an investigative report by Dada, in which he interviewed a man who confessed to a leadership role in the 1980 murder Monseñor Óscar Romero, the archbishop of San Salvador who had become a champion of El Salvador’s poor and had spoken out against government-sponsored death squads. The article was reproduced in newspapers throughout Latin America and Dada was interviewed in many television broadcasts. Like El Criminalista, such investigative journalism is the essence of El Faro’s identity, and helps push Latin American journalism as a whole to new heights.

*****

Anna Edgerton is an independent journalist based in New York. She will be writing for El Clarín in Argentina and pursuing a masters degree in international affairs from Columbia University. Follow her on Twitter.

Digital Freedom and Control

Russia and Asia

Latin America

Middle East