This article is part of the Digital Freedom and Control Project produced exclusively for the World Policy Journal by students from the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.

By Sulome Anderson

Throughout 2011’s “Arab Awakening,” some truly iconic viral videos have circulated through social media platforms. Sometimes the videos roused public opinion against governments and created a revolutionary environment; sometimes they served as a way to show the world the brutality with which governments quashed protests. Whatever their effect, experts say the phenomenon of viral video has forever changed the dynamic between states and their citizens.

“It’s that ability to broadcast that makes such an impact because of its viral nature,” says Jeffrey Ghannam, author of the report Social Media in the Arab World: Leading up to the Uprisings of 2011. “The nature of viral video is such that it takes the world to the streets.”

One example of an iconic viral video that circulated during the 2009 protests in Iran is the video of Neda, a young protester, dying from a gunshot wound. In the weeks before the Egyptian protests of 2011, there were Khaled Said’s video of Egyptian police splitting up drugs and Asma Mahfouz calling the Egyptian people to protest. All three of these videos went viral, meaning that many people uploaded them to YouTube or disseminated them on social media networks, so that they could be viewed and shared by a large number of people, sometimes numbering in the millions.

“The Internet has provided an immeasurable opportunity for people in the Middle East and North Africa to tell their stories through their own voices and with their own eyes,” says Ghannam, who wrote the report for the Center for International Media Assistance. “The ability to get online and upload video is revolutionary in and of itself.”

What makes a video go viral? Alfred Hermida, a former BBC correspondent and journalism professor at the University of British Columbia, says that a combination of factors decide how widely a video is disseminated.

“It’s difficult to predict what will strike a chord and become the iconic image of an event,” says Hermida. She also mentioned the video of Neda in Iran, saying “people were sort of fascinated and horrified by the idea that they could watch a young girl die before their eyes.”

Hermida says videos that are disseminated to the masses usually bypass traditional media. “If a mainstream journalist had captured the death of Neda, it wouldn’t have gotten as much exposure because of its violent content,” says Hermida. “But people were able to view it on YouTube and on social media.”

One of the most important aspects of viral videos is their ability to bear witness to events that might otherwise never have been viewed by the global community. Leonard Witt, communications professor at Kennesaw State University and chief blogger of the Public Journalism Network, says the seeds of this phenomenon were sowed the first time a citizen picked up a camera to document brutality by the state.

“Now, every individual can post a video to the Internet, and that is a powerful tool,” says Witt. “Tyrants don’t like to be witnessed. They don’t like exposure.”

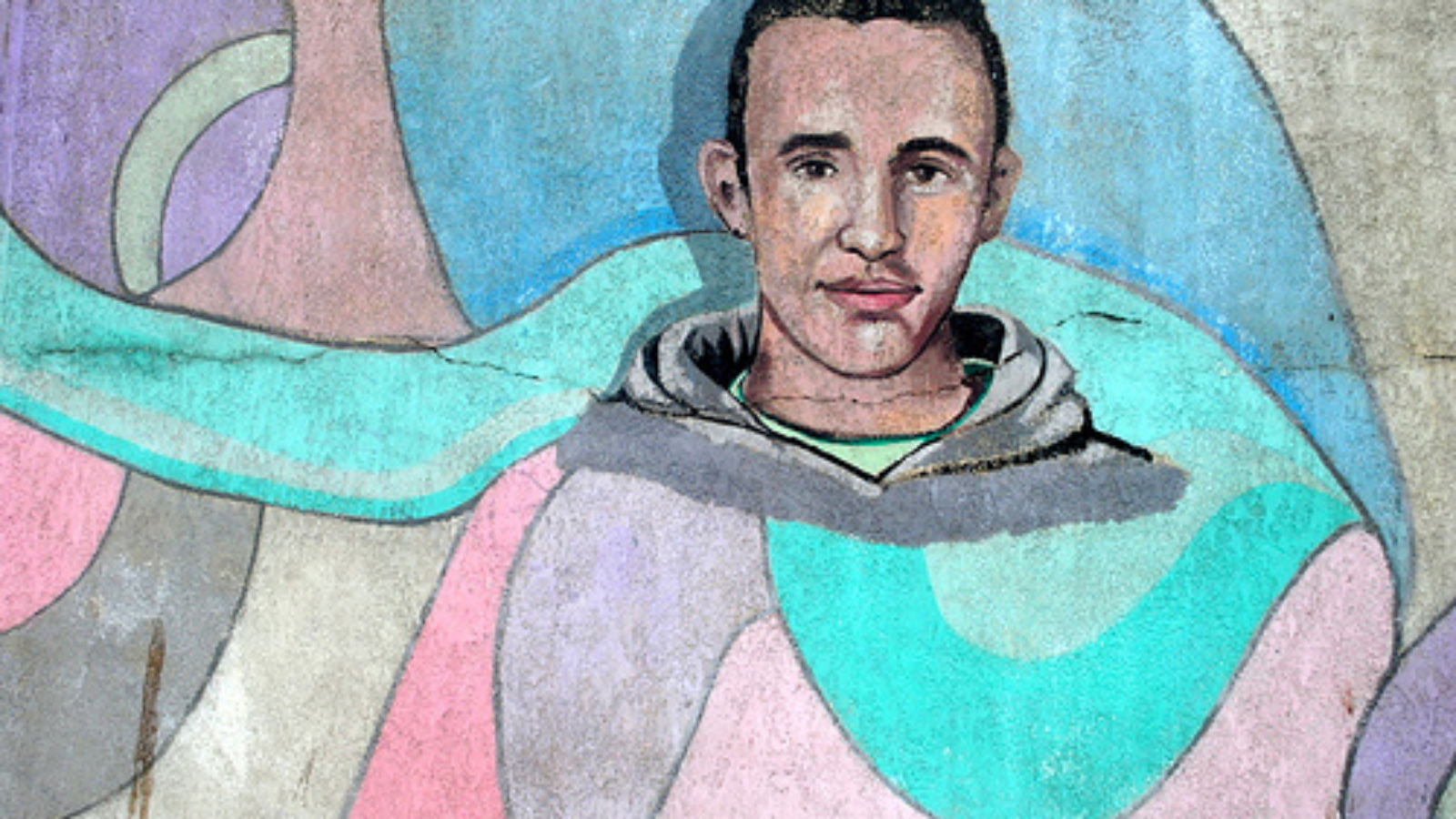

Area specialists say viral videos documenting brutality by the state may have been a factor in some of the revolutionary changes of recent months. In the case of Egyptian blogger Khaled Said, his possession of a video documenting Egyptian police dividing up confiscated drugs and discussing the possibility of selling them led to his brutal death by beating. His death prompted members of a youth movement to create a Facebook page called “We Are All Khaled Said,” which is credited by many for inciting unrest in the days before the protests.

Mohamed Abdel-Dayem, Middle East and North Africa program coordinator for the Committee to Protect Journalists, says that the video, which was widely disseminated by social media, combined with the post-mortem images of Said’s brutalized body were important triggers for the protests in Egypt.

“The video and the pictures allowed people to see the entire story of Khaled Said before and after he died in ways that simply weren’t possible before there was a platform to share images,” says Abdel-Dayem. “They basically convinced a lot of people of Khaled Said’s socio-economic class and background that they were no longer safe from state security. Up until that point, upper-middle class Egyptian society knew that things happened, but believed that they were only going to happen to Islamists or poor people. They personalized torture and made it real for people to whom it wasn’t real before.”

Stephen McInerney, Director of Advocacy at the Project for Middle East Democracy, says that another viral video that helped spark the protests in Egypt was the video of Asma Mahfouz, a young Egyptian activist and one of the founders of the April 6 Youth Movement. “She had a very poignant, 5-minute-long video of her speaking to the camera,” says McInerney. “It was very passionate and inspiring and played a not insignificant role in getting people out into the streets.”

McInerney says that in Tunisia, viral videos were a way in which citizens could follow events without having to rely on state-controlled media. “There was virtually no independent media in Tunisia, so that’s how people found out what was going on,” he says. “People were using these videos as a weapon against the government.” Some videos that were widely disseminated in Tunisia include videos of protesters chanting and police firing tear gas at protesters.

The advent of viral video has expanded the reach of mainstream media and frustrated government efforts to control coverage as they did in the past. “They [the governments] couldn’t arrest every person with a phone that has a camera,” Abdel-Dayem says. “When they shut down Al Jazeera in Egypt, Al Jazeera continued to cover Egypt using citizen footage. That created a new dynamic where news media didn’t need the blessing of the government to report the news. The state apparatus was bypassed.”

Governments have attempted to fight back against this new technology by blacking out the Internet and ruthlessly censoring Internet access. There have even been reports of governments attempting to upload their own viral videos. However, they haven’t had the same impact of viral videos uploaded by citizens, Ghannam says.

“There have been reports that governments are using viral videos and social media in ways that are dishonest and propagandistic, and it doesn’t serve the purpose of their people or the need for these governments to defend themselves,” says Ghannam. “It only further perpetrates the activists’ demands that there is a strong need for change.”

CPJ’s Abdel-Dayem suggests that these governments are fighting a losing battle. “The Internet and viral video are the only things that circumvent the government and tools that the government has developed over a number of years,” says Abdel-Dayem. “Those strategies don’t work with this new phenomenon. Even shutting down the Internet doesn’t actually work. It makes it more difficult, but it’s nowhere near the blackout that these governments are trying to establish. And the only thing that’s worse, from the government’s perspective, than no blackout, is a partial one.”

*****

Sulome Anderson is a recent gradute the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism.

Photo courtesy of Flickr user lilianwagdy.

Digital Freedom and Control